Chapter 4 Life’s secrets to make complex organic molecules

Chapter summary:

- Living organisms have a seemingly infinite complexity and diversity of molecules

- Yet, most organisms are made of 6 major atoms CHONSP assembled into four major molecular families: carbohydrates, proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids

- Complex molecules generally are polymers of simple monomers

- Each molecular family has specific structure to achieve specific function. Details of each are summarized in this chapter

- These four family constitute what we refer to as primary metabolites and are considered ubiquitous to all plants for growth and development

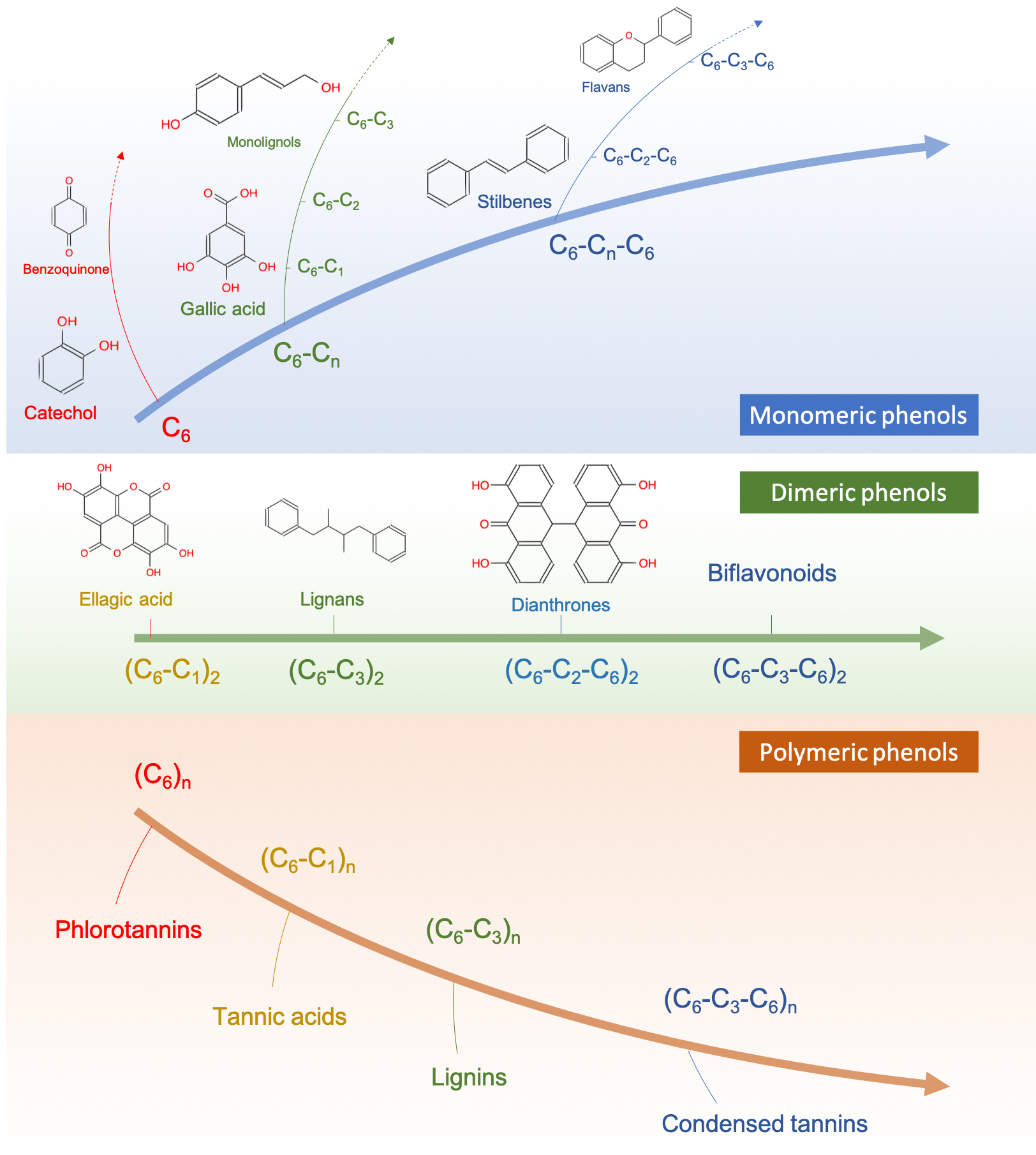

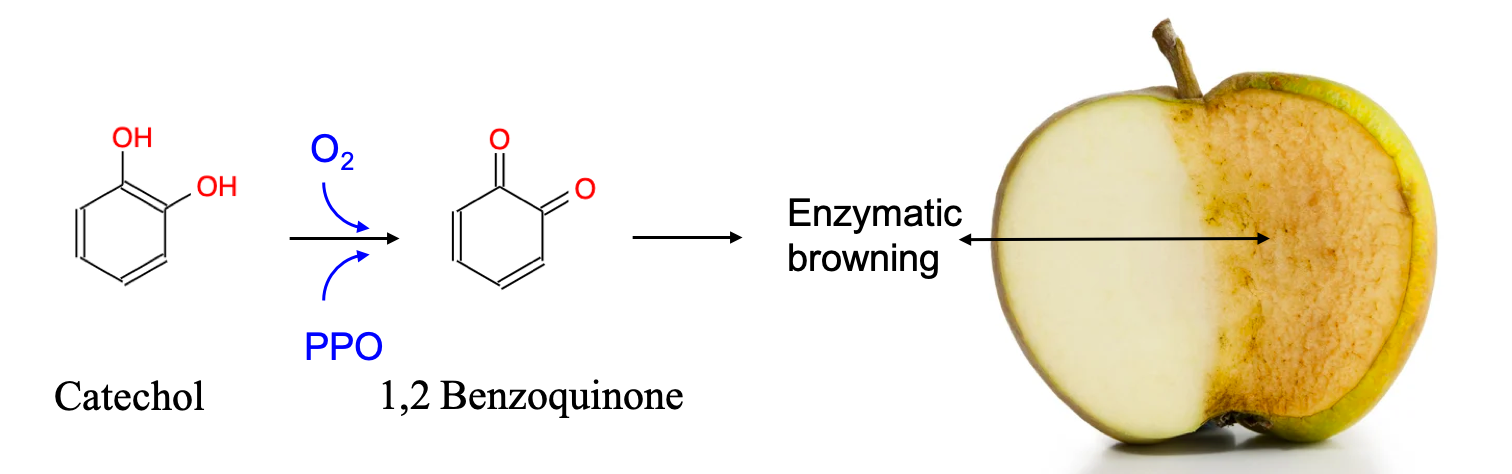

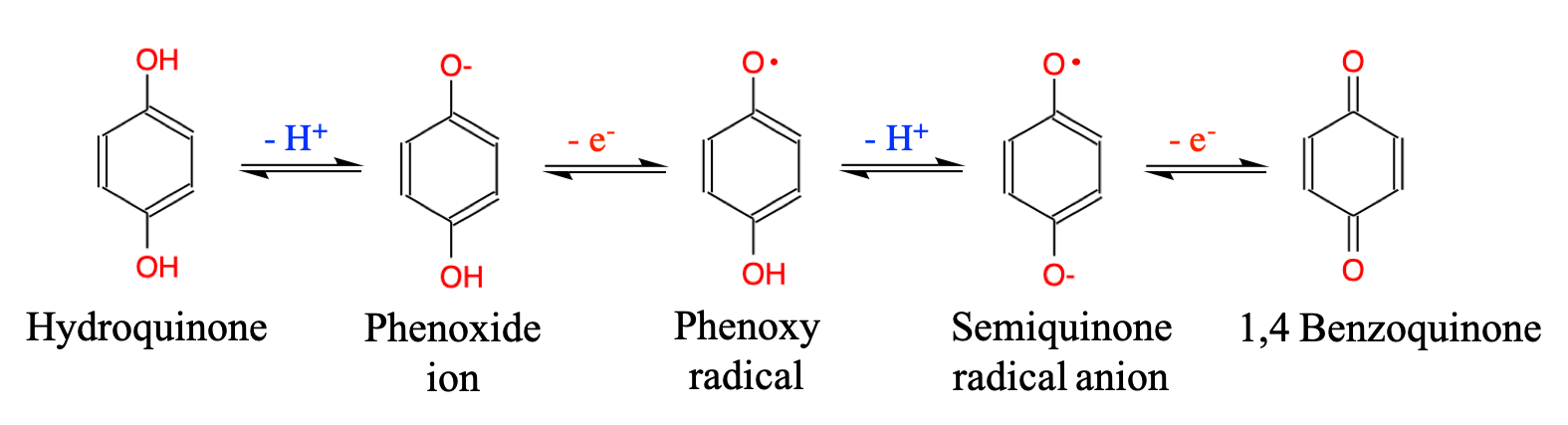

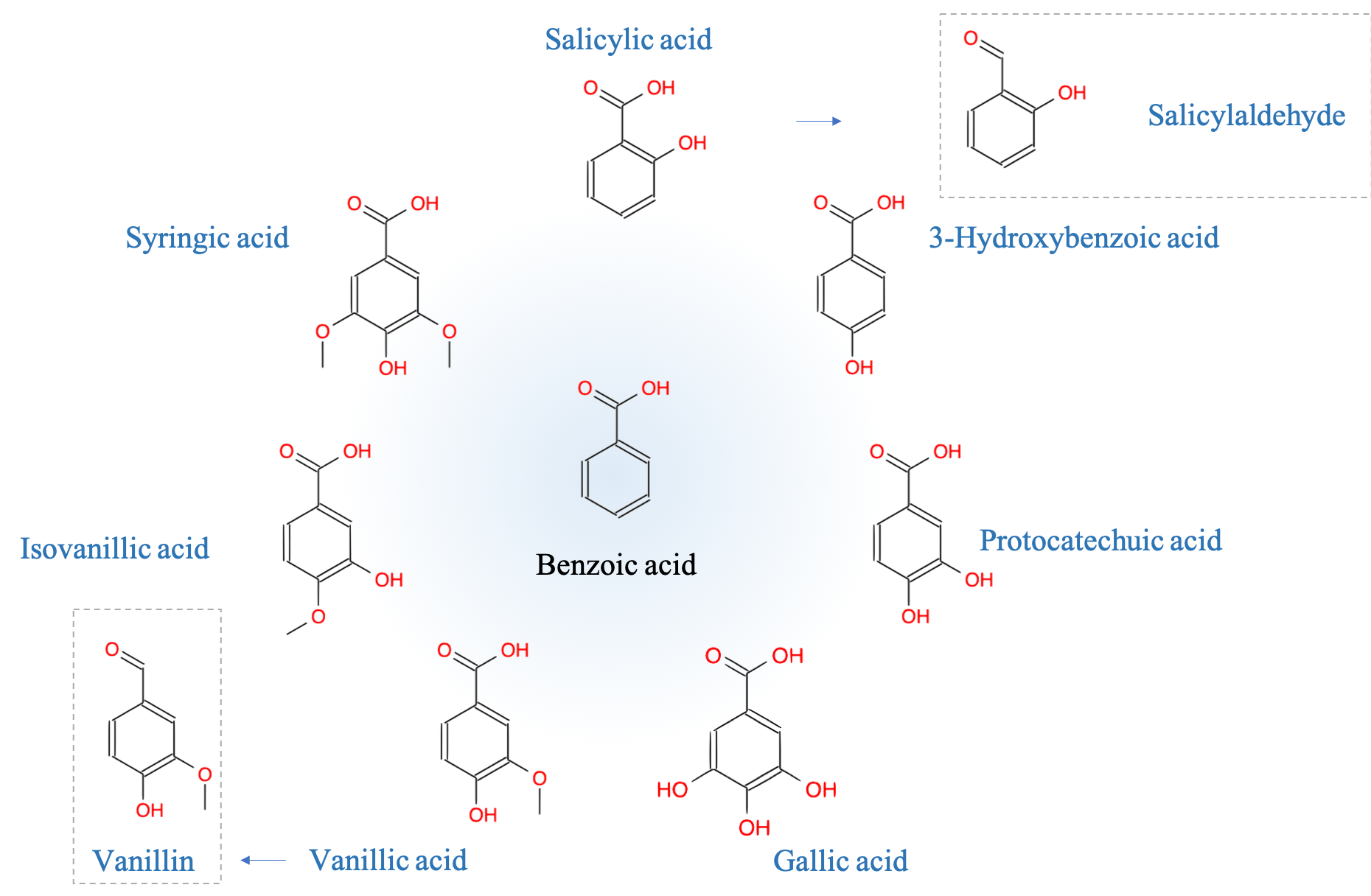

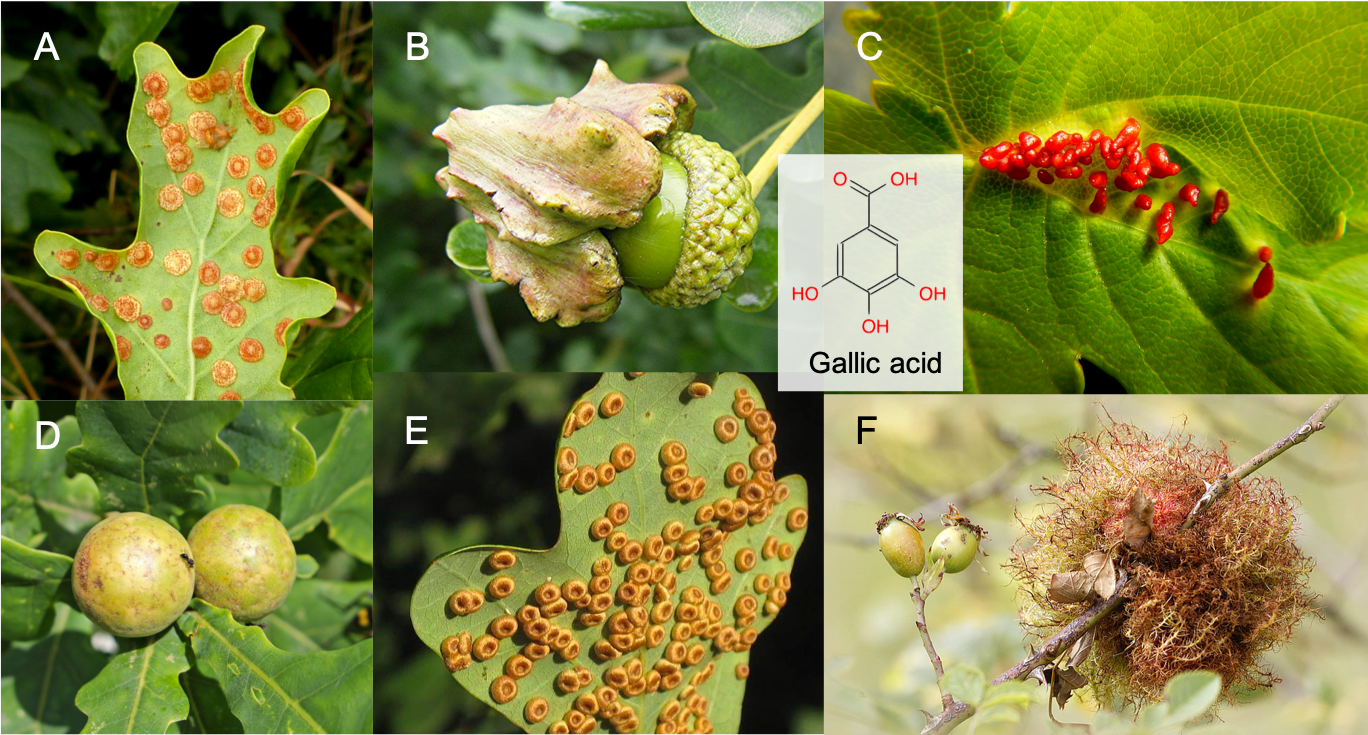

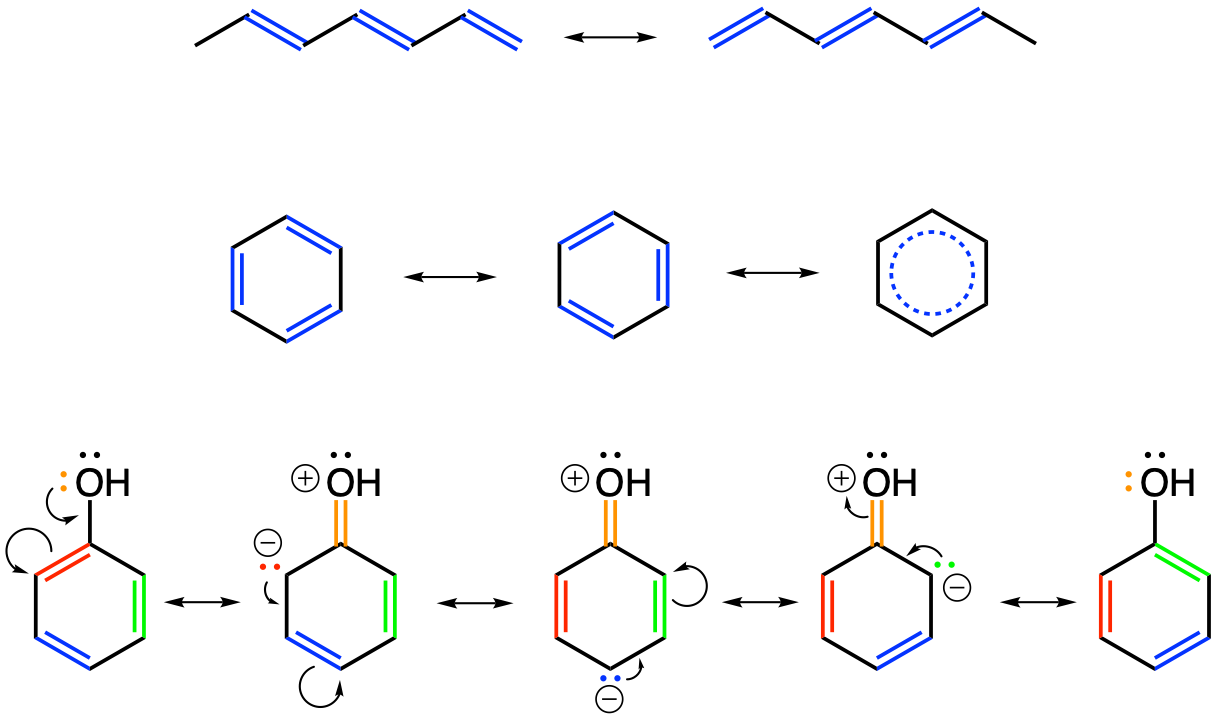

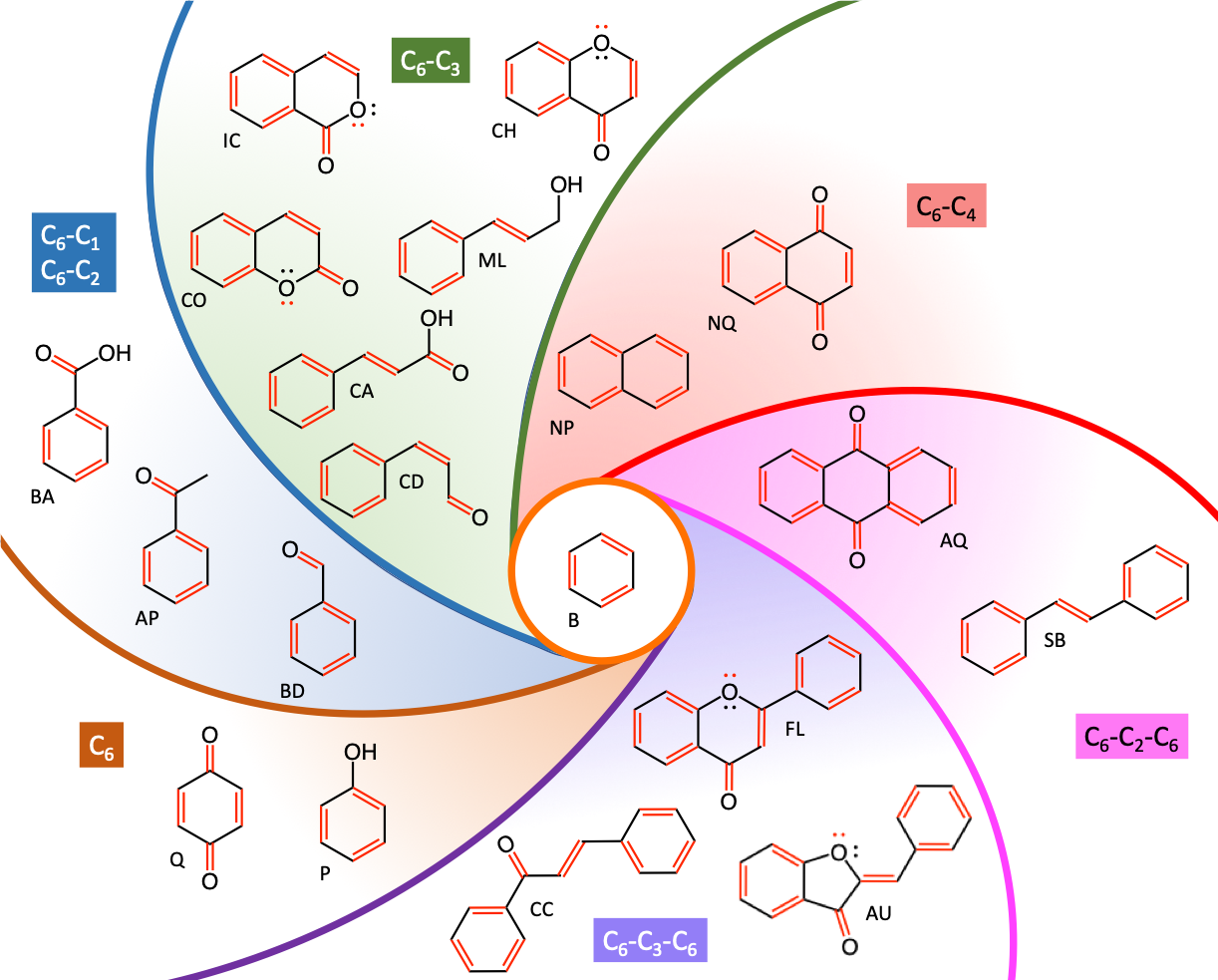

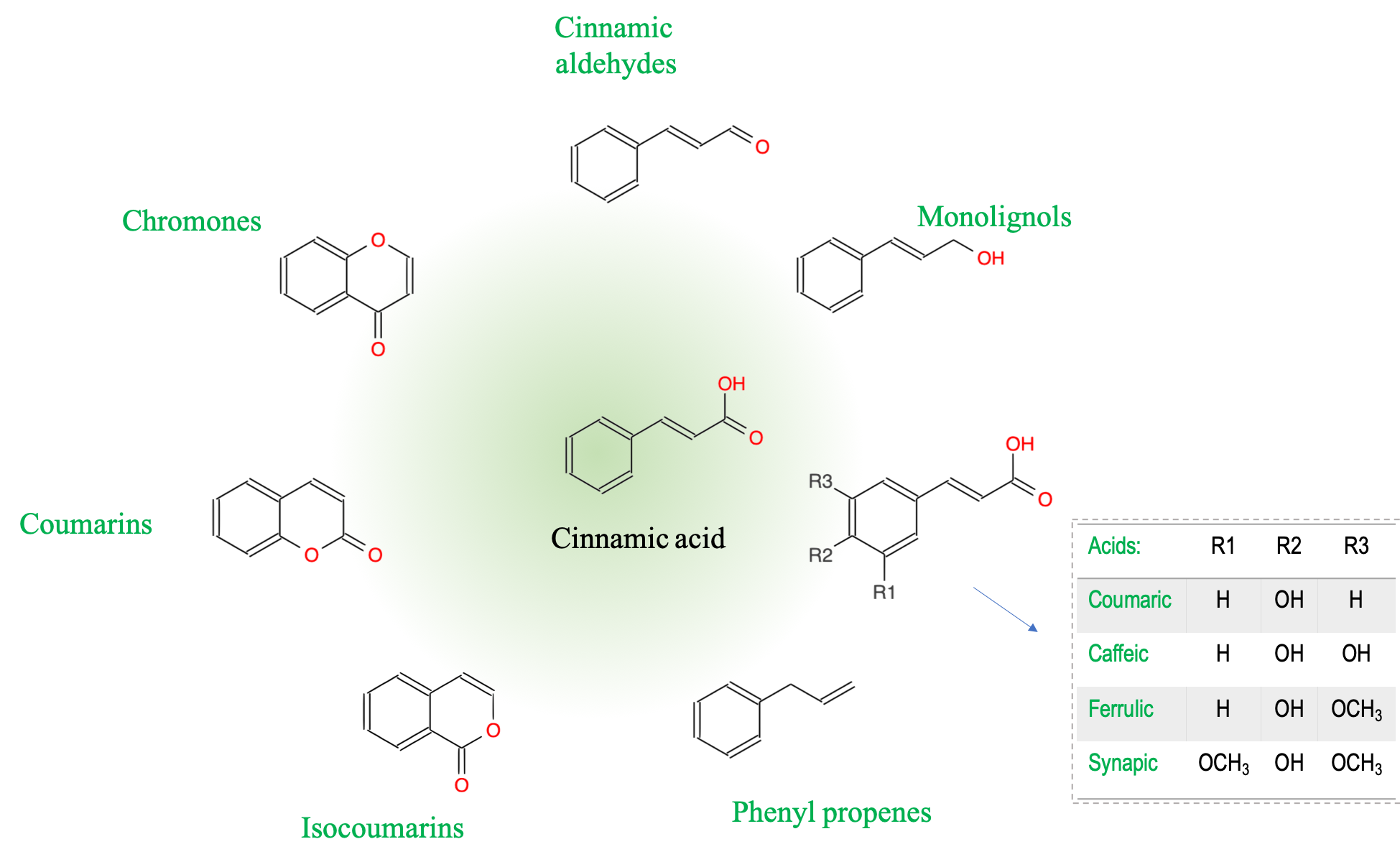

- Plants metabolize secondary metabolites, most of which are referred to as phenolics for defense against other organisms, as signaling compounds, and for protection against ultraviolet radiation and oxidants

- Phenolics play a disproportionate role in regulating microbially mediated processes in ecologically engineered treatment systems

- In organic molecules, about 4 electrons are stored on each carbon atom, none on the phosphorus, and always 8 electrons on the nitrogen and sulfur atoms

4.1 Polymers of simple monomers

When scientists of the 18th century observed nature, they thought there had to be major differences between animated organisms and the inanimate ones. In fact they thought that the elements at the basis of the animated vs. inanimate things had to be different. One can only wonder at the incredible diversity and complexity of forms between a bacterium and humans, and between unicellular algae and sequoia trees! And yet, despite the incredible variations of life forms and sizes, there is a common theme: very complex organic molecules correspond to the assemblage of simple molecules and in many cases are polymers of relatively simple monomers.

In the image of a brick wall and the skyscraper in Figure 4.1, it is possible to make a small wall or a huge skyscraper. Brick walls are made of bricks and of mortar to hold the bricks together. If one adds metal pieces, wood, etc. the complexity of the final product can be infinite, yet it is made from simple elementary pieces.

Figure 4.1: Small and large structures can be built from the addition of bricks, one at a time

Living organisms are essentially made of very complex polymers, but which are in most cases built from simple monomers. Just like in a building which complexity results from the assemblage of different types of material, e.g., bricks, wood, metal, etc., living organisms are assembled from distinct ‘types of molecules’. Among the very complex organic polymers, one can distinguish four molecular families. Molecular families can be identified because

- within a family, there are polymers of similar monomers

- the monomers are distinct between families

- and there tends to be unique chemical bonds between consecutive monomers allowing polyremisation.

The vast majority of the organic matter that makes cells and organisms have been classified into four molecular families:

- Carbohydrates

- Proteins

- Nucleic acids

- Lipids

The monomers of these four families are sometimes referred to as primary metabolites in the sense that they are ubiquitous in the plant and animal world and constitute the elementary bricks for most of the functions and structures of living creatures from bacteria to humans. This chapter will present in details the monomers and polymers for each of the family.

As I was writing this book, it became obvious that I could not ignore another important group of molecules which play a disproportionate role in ecological engineering: the phenolics. Phenolics are referred to as secondary metabolites “not directly essential for basic photosynthetic or respiratory metabolism but are thought to be required for plants’ survival in the environment. […] Secondary metabolites apparently act as defense (against herbivores, microbes, viruses, or competing plants) and signal com-pounds (to attract pollinating or seed dispersing animals), as well as protecting the plant from ultraviolet radiation and oxidants.” (Lattanzio 2013). We will explore the mystery behind these fascinating molecules.

Before we get into the details of each family and of phenolics, Table 4.1 below summarizes some of the major attributes of each of the molecular family. Although the CHONSP elements constitute organic matter in general, no one family is constituted of all these six atoms! Carbohydrates and lipids are mostly made of CHO, with additional N and P for lipids. Proteins are the only molecules where S is present. Carbohydrates and lipids play a major role in energy storage and cellular structure, while nucleic acids only store and transcribe the genetic information, and this information is transcribed into very precise sequence of amino acids forming proteins and giving them their functions.

| Carbohydrates | Proteins | Nucleic Acids | Lipids | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| General formula | CnH2nOn | CHONS | CHONP | CHO(N)P |

| Monomers | monosaccharides, hexoses | amino acids | nucleotides | fatty acids + backbone + polar head |

| Number of electrons stored | ~4 on C | ~4 on C, 8 on N and S | ~4 on C, 8 on N, 0 on P | ~6 on C, 8 on N, 0 on P |

| Cement | glycosidic bond | peptidic bond | phosphodiester bond | ester, ether, and phosphoester bond |

| Functions | Storage and transport of energy, cell and organism structure | reaction catalysis, exchange, regulation, information transfer | genetic code storage and transcription | cell structure and energy storage |

| Examples | sucrose, cellulose, starch, chitin, glycogen | enzymes, keratin, muscles, hemoglobin | RNAs and DNA | fatty acids, oils, cholesterol |

Understanding and knowing enough of the atomic and molecular makeshift of organic matter in general and of each molecular family in particular, belongs in our opinion, to the minimum ‘alphabet’ needed to better understand biogeochemical processes as organic matter is the fuel for all these processes.

4.2 Carbohydrates

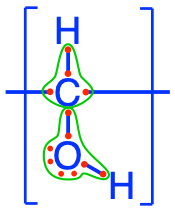

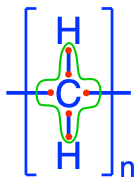

Carbohydrates form the entry molecules onto which electrons are first stored in photosynthesis, and precisely on the carbon atoms. The generic formula for carbohydrates is (CH2O)n, and each atom, on average, has 4 electrons for itself as illustrated in Figure 4.2. We have seen in the previous chapter that having 4 electrons stored on each C is probably the most cost effective way to store many electrons on organic molecules.

Figure 4.2: Electron allocation of a generic carbohydrate (CH2O)n

Carbohydrates are a rather homogeneous group as they include clearly identified monomers and polymers of these monomers. Most monomers are C6 or C5 rings and can, depending on their nature and on their polymerization type, serve very different purposes including energy storage (e.g., starch), structure (e.g., cellulose or chitin of cructacean shells), or as backbone of RNA (e.g., ribose). On an everyday life basis, carbohydrates are present in paper, sugar, pasta, grain, etc. (some common carbohydrates in food illustrated in Figure 4.3).

Figure 4.3: Assortment of everyday food containing carbohydrates. Obtained from https://www.measureup.com.au/all-about-carbohydrates/

4.2.1 Monosaccharides

The monomers of carbohydrates are called monosaccharides (from Greek monos, i.e., single, and sacchar, sugar) or called simple sugars or oses (from the Latin “full of, abounding in, having qualities of”). The monomers that are assembled into complex polymers generally are hexoses, that is that they have 6 carbons, and are isomers of glucose. However, monosaccharides do include more than just hexoses or C6H12O6, and it is important to present them in general, and not just the monomers of polysaccharides.

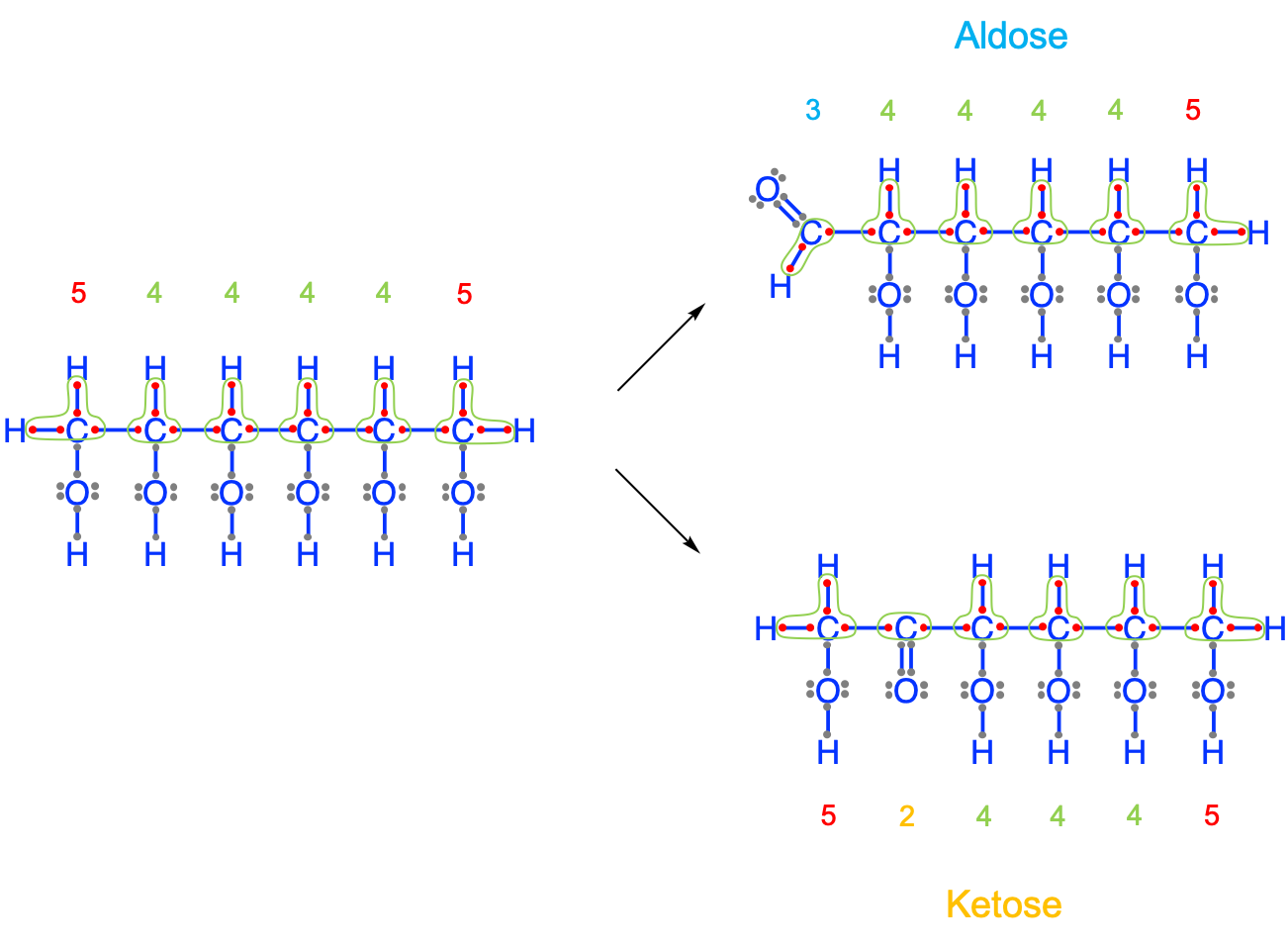

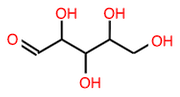

Most monosaccharides are made of 3 to 6 carbons (there actually are C7 to C9 oses) and are classified in aldoses or ketoses, depending on whether they have a aldehyde (-CHO) on their C#1 or a ketone (-C=O) radical, usually on the carbon numbered #2 (details on these functional groups in sections 3.2.9 and 3.2.10). They either exist in linear chains and are then represented in Fischer projection like in Figures 4.4 and 4.5, or, for pentoses (C5) and hexoses (C6), exist in cyclic chains (Figures 4.12 and 4.11). Carbohydrates have been given a lot of codes and naming conventions and it is hard to avoid them if we want to put things together. So, there is no reason to fear all the names and letters used to describe and differentiate carbohydrates. The goal is:

- to realize the large diversity of monosaccharides

- to realize that the differences between, e.g., the hexoses are of steric consideration, i.e., which side are the hydroxy (-OH) groups of the linear chain, right or left.

- to realize that C5 and C6 carbohydrates alternate between chain and cyclic molecular configurations. The cyclic form prevails for the functions of transport and structure that the carbohydrates provide. The chain form is the form needed for the release of electrons and energy. Both forms interchange freely for monosaccharides.

](pictures/aldoses-nb.png)

Figure 4.4: classification of C3 to C6 aldoses in Fischer projection. Triose : (1) D-(+)-glyceraldehyde ; Tetroses : (2a) D-(−)-erythrose ; (2b) D-(−)-threose ; Pentoses : (3a) D-(−)-ribose ; (3b) D-(−)-arabinose ; (3c) D-(+)-xylose ; (3d) D-(−)-lyxose ; Hexoses : (4a) D-(+)-allose ; (4b) D-(+)-altrose ; (4c) D-(+)-glucose ; (4d) D-(+)-mannose ; (4e) D-(−)-gulose ; (4f) D-(−)-idose ; (4g) D-(+)-galactose ; (4h) D-(+)-talose. after Yikrazuul — personal work, public Domain

Time to incorporate some jargon. When in the chain form necessary for the carbons to donate their electrons, monosaccharides are called reducing sugars. This means that they are able to donate their electrons, to drive respiration and the generation of energy in the cell (details in Chapter 5). So, despite the fact that each carbon atom on monosaccharides has on average 4 electrons to give, potentially, this does not systematically happen. This is rather unexpected. Indeed, for the pentoses and hexoses to be reducing sugars, they must be in the aldose form, or have a free aldehyde at the end of their chain or on carbon #1. Does this rules out the ketoses? Actually no, the ketoses in the chain form can be readily tautomerized into aldoses. This is only important to explain some of the differences in disaccharides.

](pictures/ketoses-nb.png)

Figure 4.5: classification of C3 to C6 ketoses in Fischer projection. Triose : (1) dihydroxyacetone ; Tetrose : (2) D-erythrulose ; Pentoses : (3a) D-ribulose ; (3b) D-xylulose ; Hexoses : (4a) D-psicose ; (4b) D-fructose ; (4c) D-sorbose ; (4d) D-tagatose. after Yikrazuul — personal work, public Domain

You might wonder what the D-(+) or D-(-) might mean in the legends of Figures 4.4 and 4.5… This is due to optical rotation properties that a pure solution of a particular ose has because of the asymmetry of the molecules. The different forms of hexoses in, e.g., Figure 4.4 are called eniantiomers. D means that the hydroxy group on the C#n-1 to the right of the molecule and most natural oses tend to be D (few oses have it on the left, in which case they are coded as L). The (+) or (-) tell whether the light rotation is pulled towards positive or negative angles. OK, lots of terms here, mostly to quench some of the curiosity of the biochemist in you.

The first lesson from this litany of hexoses calls for a bit of putting things together. Carbohydrates in general are the entry point for life to store high energy electrons onto carbon, via photosynthesis. All hexoses presented above, and in fact all monosaccharides, have on average 4 electrons stored on the carbon atoms. This is the most efficient way to store electrons because it consists in storing the number equivalent of the number of valence electrons on carbon in its natural state, that is 4 electrons. So carbohydrates do have, on average, 4 electrons per carbon atom. It turns out that alcohol functional groups allow the storage of 4 electons per carbon atom in a carbon chain. Carbohydrates must thus have chains of alcohol groups. However, because carbohydrates are the entry point to store energy, the elementary molecules synthesized have to be relatively small not to add weight onto leaves where they are produced and such that they can be easily transported away from the leaves into storage areas. The elementary molecules in carbohydrates are C3, C5 and C6 molecules, which fulfills the need for small molecules.

Figure 4.6: Natural formation of aldoses and ketoses from a hypothetical hexan-hex-ol to keep 4 electrons per atom on average for a C6 carbohydrate. The electrons have been allocated on the carbon atoms (green line) according to the electronegativity rule. The electrons on the oxygen atoms have been ignored because they do not participate in the storage of electrons

The result of this demonstration is that on a C6 hexose molecule, there should be 24 electrons stored. Using a chain of 6 alcohol groups yields a hexan-hex-ol, where the end carbons have 5 electrons for themselves, hence a total of 26 electrons, or 2 more than expected (Figure 4.6). The ‘solution’ nature has found is to replace one of the end alcohol groups with either an aldehyde group at the end, or another alcohol group with a ketone group. The first case leads to aldoses and the second to ketoses described above. It it thus no accident that monosaccharides have aldehyde and ketone functional groups.

For the anecdote, hexan-hex-ol isomers represented on the left of Figure 4.6 do exist in nature in small amounts and are now synthesized in the industry as thickeners and low calories sweeteners because they are poorly absorbed by the intestines. They are referred to as sugar alcohols as the suffix -itol indicates. Some names might be familiar and include xylitol, sorbitol, and mannitol. Putting C6 hex-ols into a cycle leads to inositol or cyclohexane-1,2,3,4,5,6-hexol, which is an essential compound in the brain. All of the sugar alcohols are synthesized from glucose by plants and animals.

Actually, in inositol, each carbon does have 4 electrons for itself, so nature could have kept it to store energy. However, the C-C covalent bonds are difficult to break, and nature has not kept this option. Rather, it went for glucose, the solution that could quickly store and release energy, and provide structural strength. And all that in one molecule!

Now that we have a more holistic view of what monosaccharides are made of, for all our purposes, we will reduce all this great variability to a few of them, which are glyceraldehyde (C3), ribose and deoxyribose (C5), and, glucose and fructose (C6).

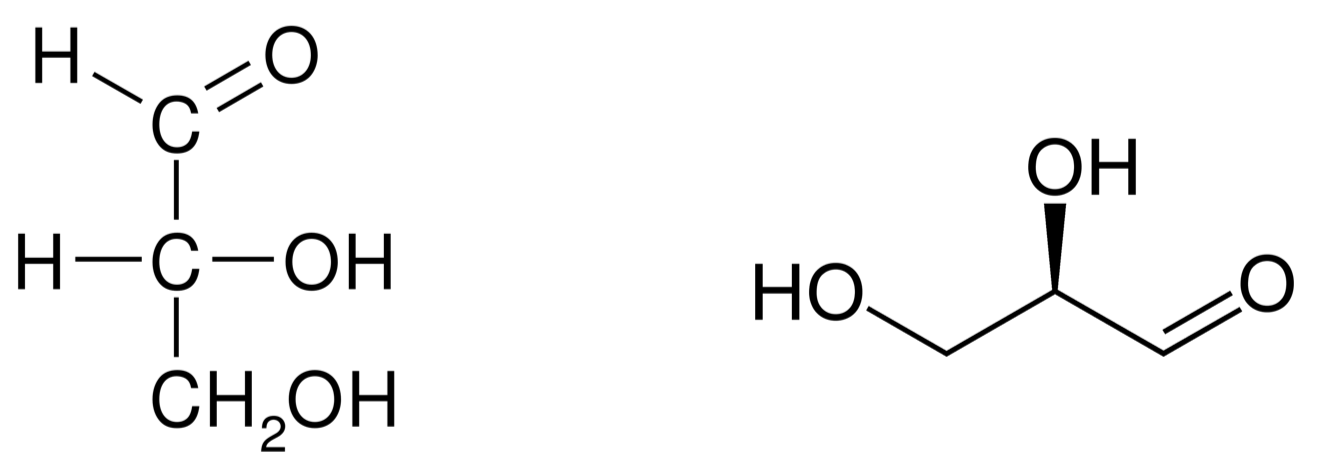

Glyceraldehyde is an important intermediate molecule of photosynthesis and is an example of the demonstration above for a C3 carbohydrate (Figure 4.7). We have seen the glycerol molecule in section 3.4, which is a propan-tri-ol, or three hydroxy group on each of the 3 carbons, which ends up as a moiety for lipids. Glyceraldehyde apparently looks like a glycerol of which an end alcohol group would be oxidized to an aldehyde group. This is technically true but it is better to view the aldehyde group as a necessity to keep 4 electrons per carbon atom.

Figure 4.7: Fisher projection (left) and skeletal formula (right) of D-glyceraldehyde

Hexose and pentose monosaccharides have two main roles: an energy release role when they are in their linear form, and a structural role when they are in their cyclic configuration as they serve as structural moeities (pentoses) and as the elementary monomers for the construction of disaccharides or more complex carbohydrates (hexoses). This might, admitedly, sound a little odd, as one might have the idea that a molecule is a rather stable physical entity. In their linear form, they can be incorporated into the metabolic pathway of cells where the electrons stored on the carbons can be released. A ‘sugar’ (i.e., the generic term also used to describe carbohydrates) that has the ability to act as a reducing agent because it has a free aldehyde group or a free ketone group, is referred to as a reducing sugar. Thanks to their ability to freely switch from a linear to a cycling form, C5 and C6 monosaccharides are reducing sugars.

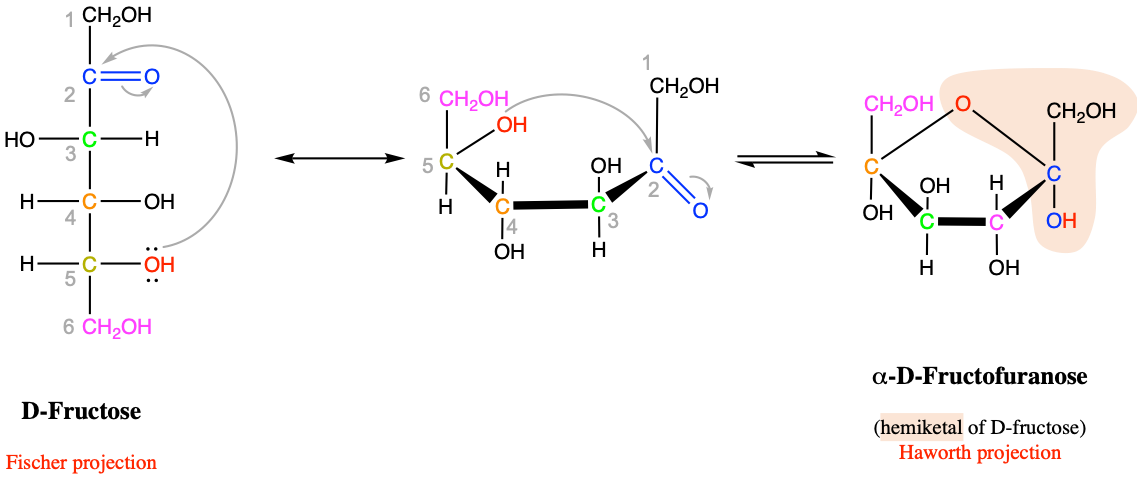

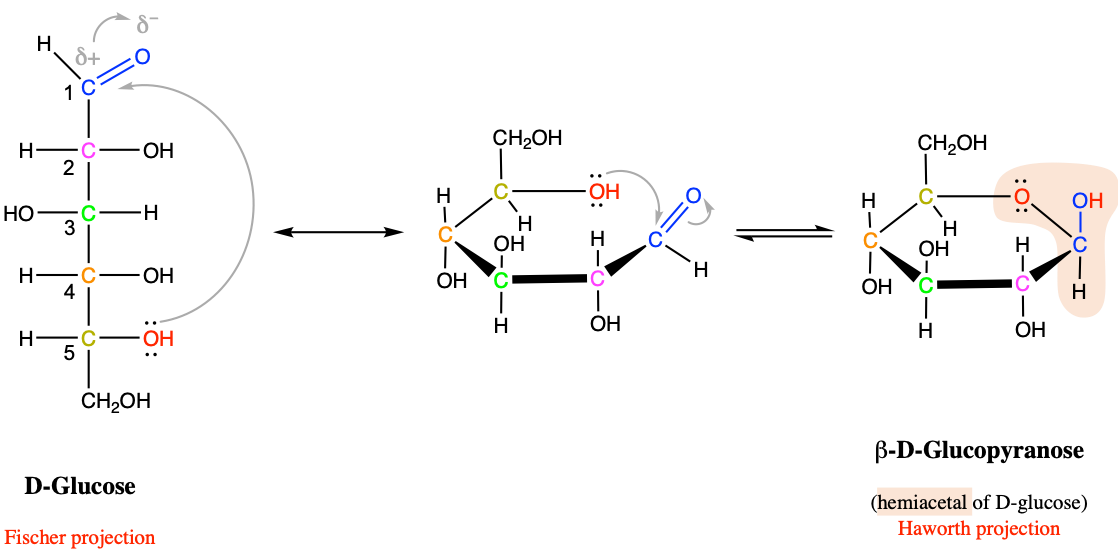

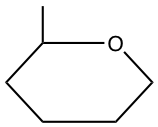

Pentoses and hexoses have the tendency to form cyclic or ring molecules “through a nucleophilic addition reaction between the carbonyl group and one of the hydroxys of the same molecule. The reaction creates a ring of carbon atoms closed by one bridging oxygen atom” (Wikipedia contributors 2018e). This property, again, is the result of the necessity to have either an aldehyde or a ketone group in the C6 chain to keep the average of 4 electrons per carbon atom. The most common rings are made of 5 or 6 atoms, respectively, with four C atoms and one O atom, and, five C atoms and one O atom (cyclic forms also referred to as furanose - Figure 4.8 - and pyranose - Figure 4.9 - , respectively, because they closely resemble furan, and pyran rings).

Figure 4.8: Intramolecular cyclic hemiketal formation in fructose and more generally for furanose hexoses

Figure 4.9: Intramolecular cyclic hemiacetal formation in glucose and more generally for pyranose hexoses

Now, as the pentoses and hexoses form rings, the acetal functional group is formed (as previously detailed in section 3.3.6). For the aldohexoses to form rings, the aldehyde on carbon #1 (Figures 4.9) reacts with the hydroxy of carbon #5 to form a 6 atom ring. And in can easily revert to the chain structure to have a free aldehyde again and be a reducing sugar. For fructose, a ketohexose, the ketone from carbon #2, reacts with the hydroxy of also carbon #5, to now form a 5 atom ring (Figure 4.8). So why is this important enough to be mentioned here…?

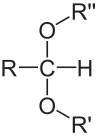

Figure 4.10: Structure of a generic acetal By NEUROtiker - Own work, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=3508032

In the ring versions of the glucose and fructose, the carbons #1 and #2 now have single bonds with two oxygen atoms. This acetal group formed by a central carbon, and bonded in a tetrahedral as illustrated in Figure 4.10 is a rather special bond. In fact, special enough that it has some interesting consequences, with two different forms. If one of the atoms bonded to oxygen is different than hydrogen (e.g., R’ and R” in Figure 4.10 both not H), then this group is called an acetal group, and the bond is a rather stable bond. If one of the R’ or R” in Figure 4.10 is H, while the other has some other radical, then the structure becomes asymmetric, the group formed is then called hemiacetal as is not nearly as stable. This explains why the hexoses may so easily switch from the linear chain to the cyclic configurations. These hemiacetal and hemiketal groups are one of the basis of the glycosidic bond, which binds the cyclic pentoses and hexoses in di- and polysaccharides, but also with other molecules.

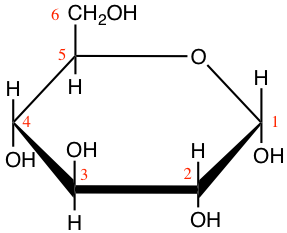

Figure 4.11: Cyclic structure or Haworth projection of alpha-D-glucopyranose (alpha-D-glucose; left) and beta-D-fructofuranose (beta-D-fructose; right)

In Figure 4.11, both glucose and fructose are hexoses. But fructose generally forms furanose rings (5 atoms, including one oxygen atom), while glucose forms pyranose rings. The α and β correspond to whether the hydroxy on the C#1 atom is below (α) or above (β) the plan made by the ring. Some more jargon here added for exactness of information only.

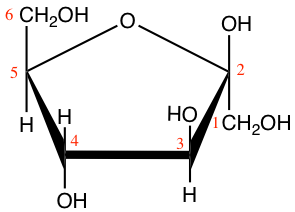

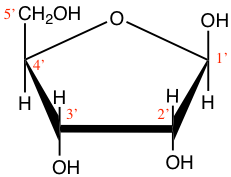

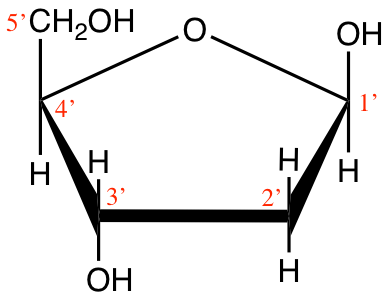

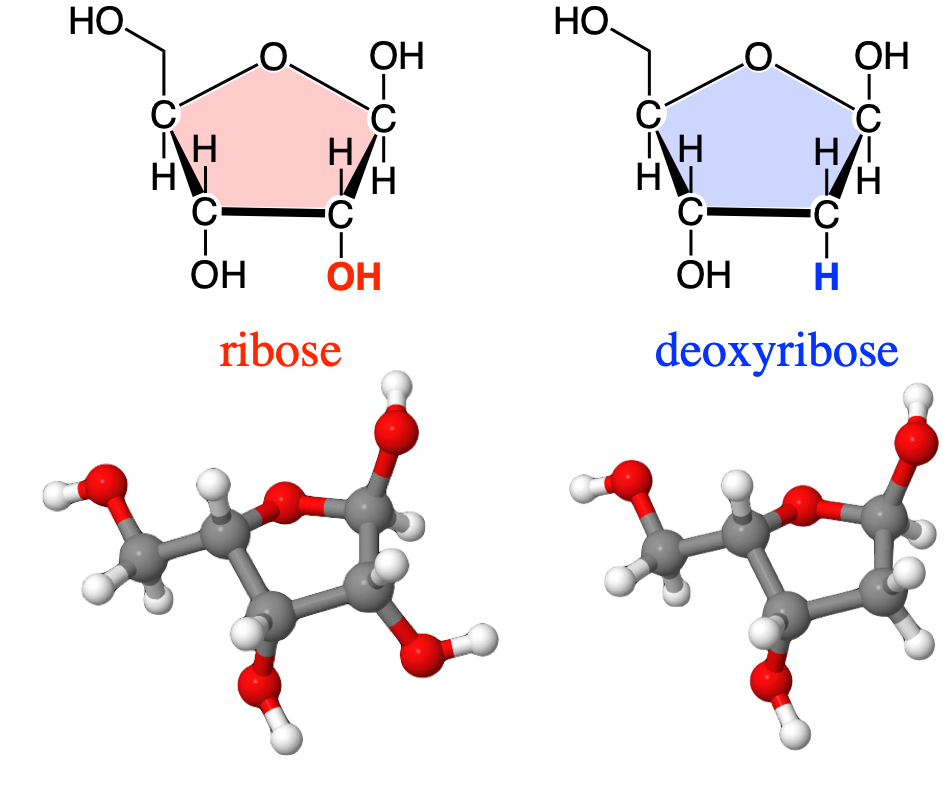

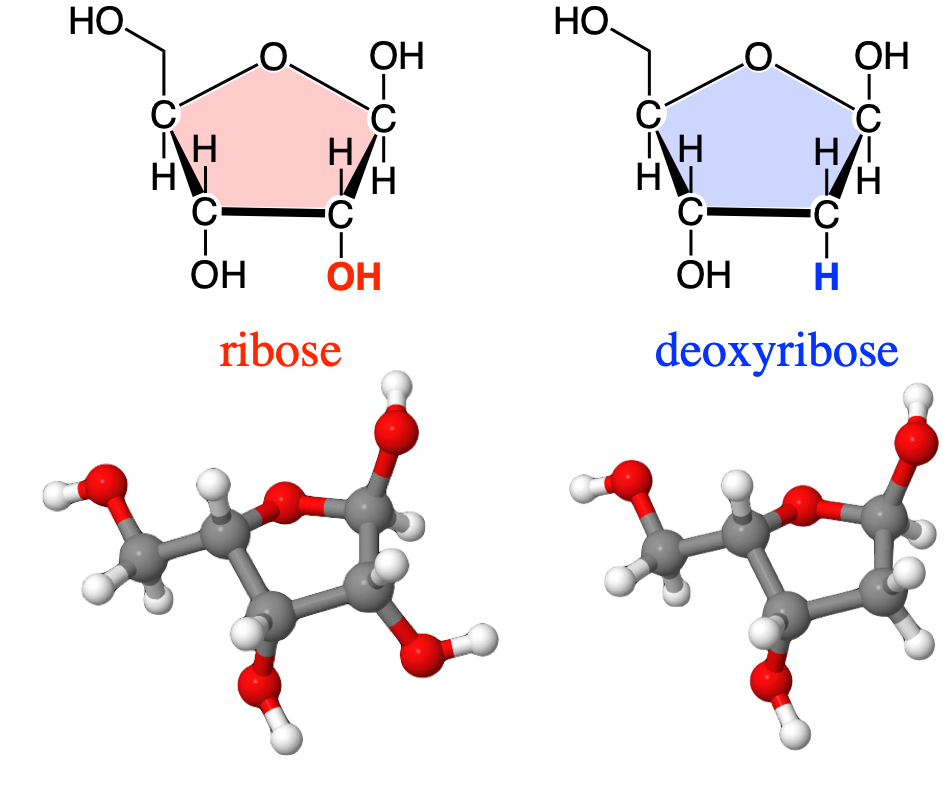

Figure 4.12: Cyclic structure of beta-D-Ribofuranose (beta-D-ribose) and 2-deoxyribose

Ribose and deoxyribose are the most important pentoses we need to know as they constitute one of the three ensembles or moeities that constitute nucleotides, i.e., the monomers of nucleic acids. They both exist either in furanose or pyranose forms, although the furanose form dominates, but the difference between ribose and deoxyribose is the missing oxygen atom on the 2’ carbon atom (Figure 4.12). And indeed, this difference is the reason for the ‘R’ and ‘D’ in the RNA and DNA molecules. Notice that the carbon atoms are numbered in Figures 4.11 and 4.12. The numbers are ‘primed’ for the ribose and deoxyribose (Figure 4.12). This is a convention that geneticists have used to differentiate the carbons from the pentose to those of the base in nucleotides (see part on nucleic acids). This is anecdotal information again.

Exercise 4.1 Draw some basic monosaccharides

In the JSME editor below, draw the molecules listed underneath. You may also render them in 3D in JSmol by going directly to JSmol demo page and click on the “JSME embedded with JSmol, for 2D⇄3D conversion” link.

Draw a ribose (C5) in its aldose form

(Ans: O=CC(O)C(O)C(O)CO))

(Ans: O=CC(O)C(O)C(O)CO))Draw the furanose form of ribose (Ans: OCC1OC(O)C(O)C1O)

Draw a aldose form of an hexose (Ans: O=CC(O)C(O)C(O)C(O)CO)

Draw a ketose form of an hexose (Ans: O=C(CO)C(O)C(O)C(O)CO)

Draw a furanose form of an hexose, e.g. fructose (Ans: OCC1OC(O)(CO)C(O)C1O)

Draw a pyranose form of an hexose, e.g. glucose (Ans: OCC1OC(O)C(O)C(O)C1O)

In summary:

Monosaccharides

- The most efficient way to capture and store energy nature has found is to store 4 electrons per carbon atom directly from photosynthesis, and the carbohydrates are the macromolecules where this storage first occurs

- Alcohol functional groups allow the storage of 4 electrons per carbon atom in a carbon chain and monosaccharides’ formula can generally be written as (CH2O)n where 3 < n < 6 generally

- To keep the relatively small C3, C5 and C6 molecules with an average of 4 electrons per carbon atom, one of the alcohol groups has to lose electrons hence the presence of aldehyde and ketone functional groups

- It is thanks to the presence, and the steric configuration, of the aldehyde and the ketone groups that C5 and C6 molecules readily alternate between linear and ring forms, the latter existing thanks to hemiketal and hemiacetal functional groups

- It is thanks to the rather unstable nature of the hemiketal and hemiacetal functional groups that the monosaccharides can easily switch configurations from linear chains where they can fulfill their role as electron donors, and cyclic rings where they act as structural monomers of di- and polysaccharides for the hexoses or as structural moieties for pentoses

- Thanks to all the hydroxy groups, monosaccharides are extremely soluble in water

- Small differences in the position of the hydroxys, and in the cyclization of the C5 and C6 make for different monosaccharides

- The C3 atom monosaccharide to remember is glyceraldehyde

- Glucose is arguably the most important monosaccharide and the only hexose molecule expected to be known by heart

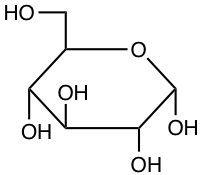

For glucose, and for organic chemistry in general, there are several ways of representing molecules. One of the ways is the Haworth projection as shown in Figures 4.11 and 4.12. Another way is called the Fischer projection as illustrated in Figures 4.4 and 4.5. Another way is called the skeletal formula where the carbons are implied at the corners and the ends of line segments, while oxygen and other remarkable radicals such as hydroxy or amine are noted. Glucose is thus often represented as skeletal formula as in the left of Figure 4.13. Another even more simplified representation of glucose is represented in the ‘hyper’ skeletal formula. The latter has the advantage to be simple enough and used to illustrate polysaccharides.

Figure 4.13: Skeletal formula for alpha-D-glucose (left), ‘hyper’ skeletal formula (center), and 3-D representation with C in grey, O in red, and H in white. Notice that in 3-D, the pyranose ring is not flat. It would if it were an aromatic ring

In reality, there is an entire field of chemical research that deals with the representation of molecules, often in 3D, using computer graphics. A scalable 3-D representation of alpha-D glucose can be directly visualized at this location for example.

4.2.2 Dissacharides

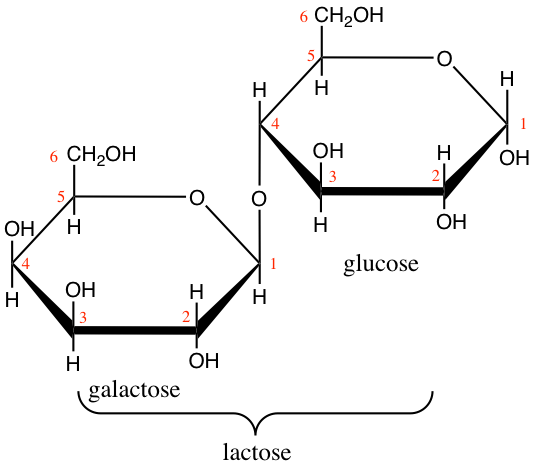

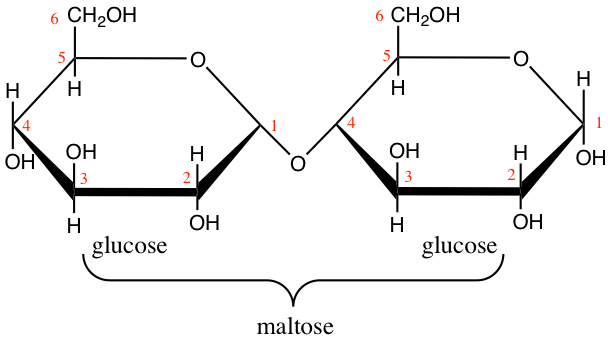

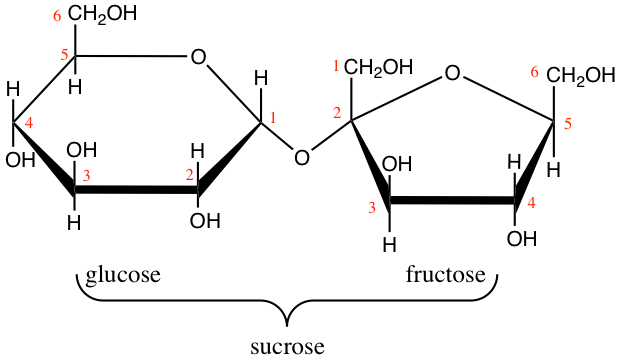

Sucrose, lactose, and maltose are three common dissaccharides. Dissacharides are bioses or polymers of two hexose monomers. Because they are still small, and thanks to their solubility in water (thanks to hydroxy groups), they play an essential role to transport energy in chemical forms because for a slight increase of the osmotic pressure in a liquid, dissaccharides carry twice the number of electrons.

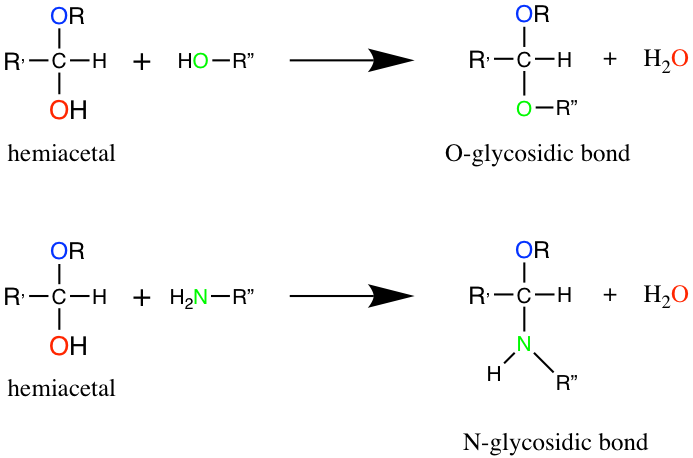

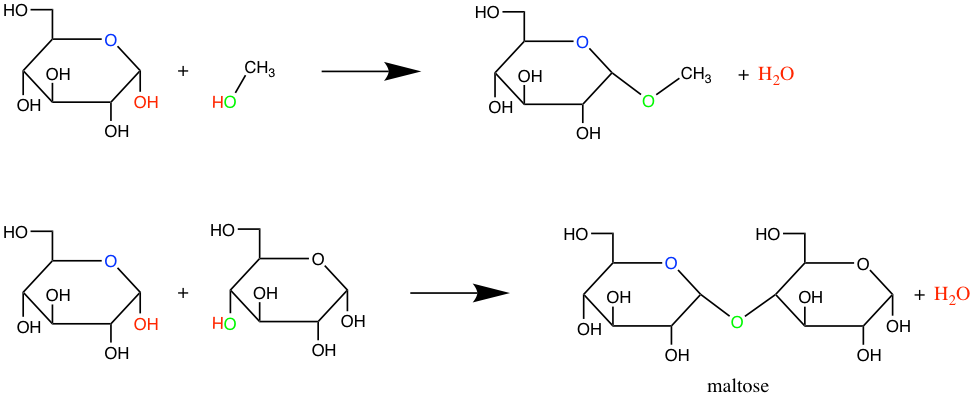

Dissaccharides correspond to the assemblage of two monosaccharides thanks to the glycosidic bond. The name of this bond suggests that it is very specific to carbohydrates, and it is true as one monosaccharide must be involved in a glycosidic bond. So the glycosidic bond is a type of covalent bond that joins a carbohydrate (sugar) molecule to another group, which may or may not be another carbohydrate. The common theme, however, is that the carbon of the sugar involved corresponds to that of the hemiacetal group. There are 4 types of glycosidic bonds, depending on the atom directly linked to the hemiacetal carbon of the carbohydrate: O-, N-, S-, or C-glycosidic bonds. Figure 4.14 illustrates the generic O- and N-glycosidic bond.

Figure 4.14: Formation of glycosidic bonds between a hemiacetal Carbon and a hydroxy or amine group, to respectively form O- and N-glycosidic bonds.

The N-glycosidic bond occurs in nucleotides and thus plays a major role. But overall, the term glycosidic bond generally refers to the O-glycosidic bond between two consecutive monosaccharides (Figure 4.15). In the end, and to go back to the brick and mortar analogy, for di- and polysaccharides, the glycosidic bond is the equivalent of the mortar.

Figure 4.15: Formation of glycosidic bonds between a glucose hemiacetal carbon and a methyl hydroxyde (top) or between two glucoses to form maltose

Lactose and maltose (Figure 4.16) are dissaccharides, respectively assembled from a galactose and a glucose, and, from two glucose molecules. Notice that these two molecules are reducing sugars, i.e., there is one hemicetal carbon (C#1) free to potentially open one glucose into a chain form, hence the ability for both lactose and maltose to be readily available as electron donors. This is quite nice for lactose produced by mammal females to be readily available for their offsprings. On another note, during seed germination, starch (details below) is hydrolyzed into maltose first by the amylase enzyme, and then readily participate in energy generation for this critical time of seed plant lives.

Figure 4.16: Lactose and maltose dissaccharides molecular formulae

Interestingly, sucrose in not a reducing sugar as both hemiacetal carbons (C#1 of glucose, and C#2 of fructose) are part of the glycosidic bond (Figure 4.17). There are several advantages:

Figure 4.17: Sucrose molecular formula

- Sucrose is a very stable molecule, and a lot more than lactose and maltose. Hydrolysis of the glycosidic bond is very slow and solutions of sucrose can last for a very long time.

- Because both hemiacetal carbons are bonded, there are no more possibilities for an additional glycosidic bond to take place: sucrose stays as a dissaccharide

This is actually essential for green vascular plants, which assemble sucrose in their leaves from glucose and fructose, but must transport these molecules away from the leaves to minimize weight and avoid jamming of the photosynthesis. So having a very stable, highly soluble, not polymerisable, non reducing molecule is very advantageous. Sucrose can then be hydrolyzed thanks to the sucrase enzyme into glucose and fructose again for use or storage at other places in the plants.

Exercise 4.2 Draw some basic dissaccharides

In the JSME editor below, draw the molecules listed underneath. You may also render them in 3D in JSmol by going directly to JSmol demo page and click on the “JSME embedded with JSmol, for 2D⇄3D conversion” link.

Draw a molecule of sucrose: non-reducing sugar involving glucose-fructose (hexofuranose) with a 1 - 1 link (Ans: OCC2OC(OC1(CO)OC(CO)C(O)C1O)C(O)C(O)C2O)

Draw a molecule of maltose: reducing sugar involving glucose-glucose with a 1 - 4 link (Ans:

OC[C@H]2O[C@H](O[C@H]1[C@H](O)[C@@H](O)C(O)O[C@@H]1CO)[C@H](O)[C@@H](O)[C@@H]2O(isomeric SMILES) or- OCC2OC(OC1C(O)C(O)C(O)OC1CO)C(O)C(O)C2O) (canonical SMILES)

Draw a molecule of lactose: reducing sugar involving galactose-glucose with a 1 - 4 link (Ans:

C([C@@H]1[C@@H]([C@@H]([C@H]([C@@H](O1)O[C@@H]2[C@H](O[C@H]([C@@H]([C@H]2O)O)O)CO)O)O)O)O(isomeric SMILES) or- OCC2OC(OC1C(O)C(O)C(O)OC1CO)C(O)C(O)C2O) (canonical SMILES)

Notice that the difference between lactose and maltose is only isomeric, the formula is exactly the same.

In summary:

Disaccharides

- The glycosidic bond always involves one hemiacetal group and is the key for the formation of carbohydrate dimers, and also polymers

- Dissacharides are small molecules which are easily soluble thanks to the many hydroxy groups and easily transportable

- For a very similar osmotic pressure, dissaccharides carry twice as many electrons as monosaccharides: dissaccharides are the ‘go to’ transport molecules

- Sucrose, a very stable molecule, non reducing sugar, is the molecule used by vascular plants to transport the products of photosynthesis (glucose and fructose) from the leaves to storage areas (both sometimes located very far apart - think about sequoias!)

4.2.3 Polyssaccharides or glycans

Polysaccharides are polymers of monosaccharides linked together thanks to the glycosidic bond, forming sometimes very long chains (at least more than 10 monosaccharides, or else are referred to oligosaccharides), either linear or branched. The polysaccharide chains are also referred to as glycans, the suffix an implying a chain of monosaccharides. In glycan, the prefix glyc refers to the generic carbohydrate. The term glucan refers to a chain of glucose monomers, similarly, the term xylan, refers to a chain of xylose monomers, and so on.

Polysaccharides generally have two main functions: energy storage or structure. Because of the glycosidic bond, which removes a molecule of H2O, the general formula for a large polysaccharide is more like (C6H10O5)n often with 200 < n < 3500. For our purpose, it is important to remember that there are three main polysaccharides: homopolysaccharides or homoglycans, i.e., long chains of the same monomers (homo: same), and heteropolysaccharides or heteroglycans, long chains of a variety of monomers (hetero: different), generally separated into hemicelluloses and pectins.

4.2.3.1 Homopolysaccharides or homoglycans

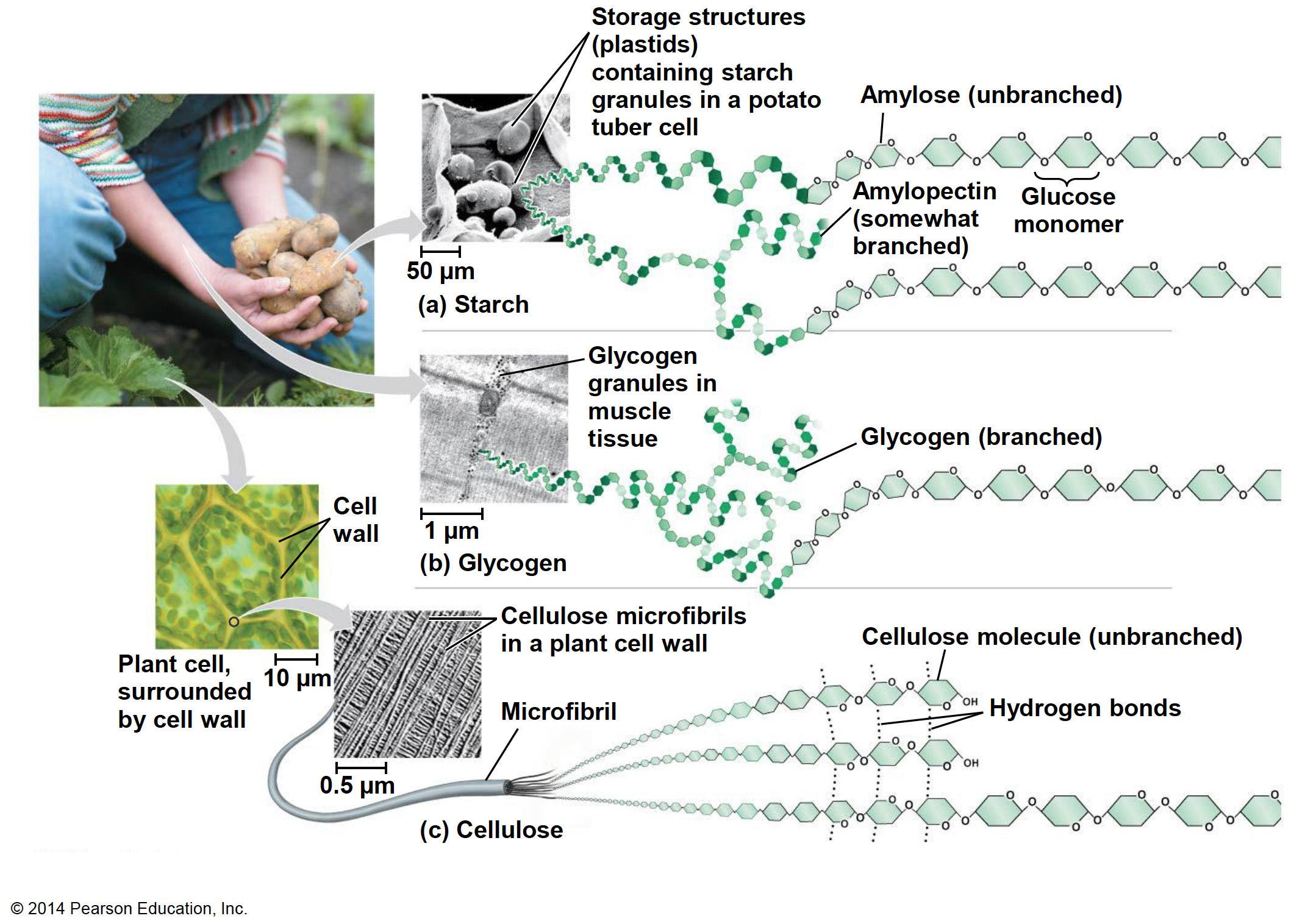

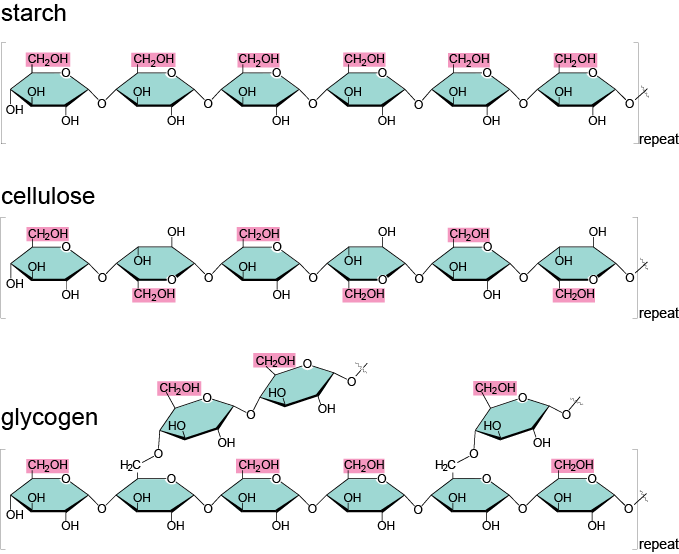

Among the most important homopolysaccharides, one can distinguish starch and glycogen, which are both energy storage molecules for plants, and animals, respectively, and, cellulose which has a structure function making a lot of the plants cell walls (Figure 4.18).

Figure 4.18: Starch, glycogen, and cellulose are the three main homopolysaccharides of importance for our field. Obtained from https://www.sedelco.org/cms/lib/PA01001902/Centricity/Domain/506/05_Lecture_Presentation.pdf

All three molecules are polymers of α- and β D-glucoses. Starch is a polymer of α-D-glucoses linked together by carbons 1 and 4. Glycogen has essentially the same structure, although it has some branches thanks to a bond between carbon 4 and 6 (Figure 4.19).

Figure 4.19: Illustration of the 1-4 links between monomers of alpha-D-glucose for starch, plus 4-6 links to form branches for glycogen, and 1-4 links between monomers of beta-D-glucose for cellulose. Obtained from https://biochemikages005.wordpress.com/2014/02/10/carbohydrates/

Before we go on on describing the molecular structure of polysaccharides, it is time to reflect on their significance at the planet scale. Cellulose is the most abundant organic polymer on earth (Klemm et al. 2005). Thanks to the hydrogen bonds between adjacent β-D-glucose polymers, very strong cellulose microfibrils form, themselves bundled into macrofibrils, surrounded by hemicelluloses and lignin (Figure 4.20). Cellulose molecules can be hydrolyzed thanks to the cellulase enzyme, generally secreted by bacteria, although animals such as termites do produce a cellulase. Most mammals only have a limited ability to digest cellulose fibers, and even ruminants and monogastric herbivores use symbiotic bacteria to produce cellulase.

).](pictures/cellwall_carbohydrates.gif)

Figure 4.20: Illustration of Cellulose strands surrounded by hemicellulose and lignin in plant cell walls (Department of Energy’s Genomic, 1986).

So if cellulose is the most abundant molecule on earth, one needs to pause in the structure description of polysaccharides and locate where polysaccharides play a role. Cellulose is the basic structure of plant cell walls. Plant cells, are distinctively different from animal cells because of their cell wall. It is the resemblance with honeycomb cells that Robert Hooke coined the term cell for plants in 1665, the shape being well defined and distinctive thanks to the walls. The cell wall is located externally to the plasma membrane and is synthesized by the cell itself.

Morphologically, the cell wall is formed by layers or sheets. All cells have at least two: middle lamella and primary wall. The middle lamella is synthetized and shared by cells that are contiguous with each other, while the primary cell wall is synthetized and belongs to each cell. In some plant cells, a third thicker layer called secondary cell wall is deposited between the membrane and the primary wall. Most of the wood in the trees correspond to the secondary cell wall (Figure 4.21) (Pacheco Megías, Molist García, and Pombal Diego 2013)

[@Pacheco_Megias2013-ov].](pictures/cell-walls2.png)

Figure 4.21: Illustration of plant cell walls. In some cells, three layers can be distinguished in the secondary cell wall: S1, S2, and S3 layers are sometimes present, each with a different orientation of its fibers of cellulose. Obtained from the Atlas of Plant and Animal Histology (Pacheco Megías, Molist García, and Pombal Diego 2013).

The outermost layer of the cell wall and the first to form is the middle lamella. It acts as a glue that binds neighboring cells. The middle lamella consists mainly of pectins, although it can be lignified in those cells that have a secondary cell wall. The primary wall consists mainly of cellulose, hemicellulose, pectins, glycoproteins. For the cells that have one, the secondary wall consists mainly of cellulose, hemicellulose and lignins [Figure 4.22; Pacheco Megías, Molist García, and Pombal Diego (2013); Loix et al. (2017)].

![Illustration of the glycans structure of plant cells with primary wall only (A), and plant cells with both primary and secondary walls (B) [@Loix2017-pv].](pictures/cell-walls3.jpg)

Figure 4.22: Illustration of the glycans structure of plant cells with primary wall only (A), and plant cells with both primary and secondary walls (B) (Loix et al. 2017).

Of these different classes, only cellulose is well defined, consisting entirely of β-(1→4)-linked glucan chains. Pectin are highly heterogeneous polysaccharides, traditionally characterized by being relatively easily extracted with hot acid or chelators and by containing a large amount of galacturonic acid residues. Hemicelluloses traditionally comprise the remaining polysaccharides […] (Scheller and Ulvskov (2010))

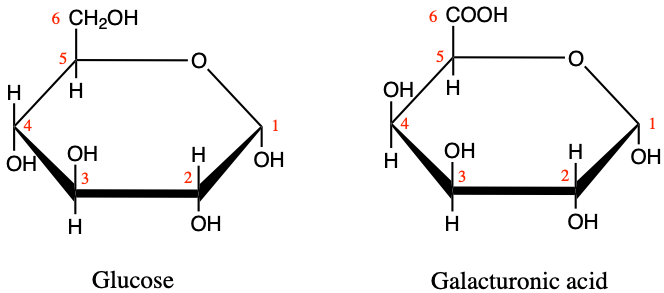

4.2.3.2 Pectins

Pectins are heteroglycans based on galacturonans, or polygalaturonic acids, i.e. polymers of galacturonic acid monomers. For comparison purposes, the difference between glucose and galacturonic acid is illustrated in Figure 4.23 below. The alcohol functional group of glucose on C6 is oxidized into a carboxylic acid group, and the hydroxy on C4 changes side. The main role of pectin is to give physical strength to the plant and to provide a barrier against the outside environment (Harholt, Suttangkakul, and Vibe Scheller 2010). Pectins also hold cells together. Fruit ripening (becoming softer) or leaf fall, are in part due to the decomposition of pectins by pectinase enzymes. Pectins also seem to play a role during seed germination, and as such also have an energy storage role, particularly thanks to the galactans and arabinans (Harholt, Suttangkakul, and Vibe Scheller 2010; Scheller and Ulvskov 2010)

Figure 4.23: Illustration of the differences between alpha-D-glucose and D-galacturonic acid monomers.

Harholt, Suttangkakul, and Vibe Scheller (2010) classify pectins in four categories (Figure 4.24):

- the homogalacturonans (HG), which are relatively homogeneous galacturonans, although some acetyl (-C=O-CH3) or methyl (-CH3, more details herein) groups can be added. These are the most abundant, ~65% (Harholt, Suttangkakul, and Vibe Scheller 2010)

- the xylogalacturonans (XGA), for which some xylose monomers are added to the the galacturonan chain thanks to the glycosidic bonds. XGA appear to be minor components of pectins.

- the Rhamnogalacturonans II (RGII), which still hold the galacturonan as the basic chain, but with complicated carbohydrate chains, containing rhamnose monomers in particular. RGII appear to be minor components of pectins.

- and the Rhamnogalacturonans I (RGI), for which rhamnose monomers alternate between galacturonic acids and that side carbohydrate side chains of arabinans and galactans. RGI constitute between 20-35% of the pectins.

![Illustration of the general types of pectins. Notice that the common structure or pectin backbone (but for RGI) is the polymer of galacturonic acids, or galacturonan, to which, quite a diversity of monomers participate resulting in the large heterogeneity of these heteroglycans [@Harholt2010-ox].](pictures/pectins.jpg)

Figure 4.24: Illustration of the general types of pectins. Notice that the common structure or pectin backbone (but for RGI) is the polymer of galacturonic acids, or galacturonan, to which, quite a diversity of monomers participate resulting in the large heterogeneity of these heteroglycans (Harholt, Suttangkakul, and Vibe Scheller 2010).

Again, this information is provided to expose readers to the extraordinary diversity of carbohydrates, and are not meant to be known in great details. It is important to remember that in addition to homoglycans, there are galactorunans, on which pectins are based.

4.2.3.3 Hemicelluloses

Hemicelluloses are heteroglycans or heteropolysaccharides. The hemicellulose term was coined at a time when the structures were not well understood and biosynthesis was completely unknown. Hemicellulose is recognized as a group of wall polysaccharides that are characterized by being neither cellulose nor pectin and by having β-(1→4)- linked backbones of glucose, mannose, or xylose (Figure 4.25). These glycans all have the same equatorial configuration at C1 and C4 and hence the backbones have significant structural similarity (Scheller and Ulvskov 2010). For those of you who are curious about the ‘equatorial configuration’ term used here, this has to do with the steric configuration of the hydroxy groups in the cyclic configuration of monosaccharides. This was not even introduced in this chapter, although it is an important consideration for chemists to characterize carbohydrates!

![Illustration of the general types of hemicelluloses, which vary among species and plant groups. Notice the nomenclatures ending in *-an*, suggesting polysaccharides. OMe, represents methyl groups; Ac, represents acetyl groups; “Fer” represents esterification with ferulic acid (3-methoxy-4-hydroxycinnamic acid) [after @Scheller2010-ep].](pictures/hemicelluloses_final.png)

Figure 4.25: Illustration of the general types of hemicelluloses, which vary among species and plant groups. Notice the nomenclatures ending in -an, suggesting polysaccharides. OMe, represents methyl groups; Ac, represents acetyl groups; “Fer” represents esterification with ferulic acid (3-methoxy-4-hydroxycinnamic acid) (after Scheller and Ulvskov 2010).

The most important biological role of hemicelluloses is their contribution to strengthening the cell wall by interaction with cellulose microfibrilsand, in some walls, with lignin (e.g., Figure 4.21). All the hemicelluloses show differences in structural details between different species and in different cell types within plants (Figure 4.25).

In summary:

Polysaccharides

- Polysaccharides or glycans are formed by the polymerization of mostly hexose monomers, although pentoses are sometimes involved, via the glycosidic bond

- The atoms involved in the glycosidic bonds determine whether the polymer is linear or branched, and ultimately determines the type of polysaccharides

- The energy stored on polysaccharides is not available unless the hexoses are liberated one by one or two by two (starch → maltose) from the polysaccharides chains

- Cellulose is the most abundant organic polymer on earth present in all plant cell walls

- Pectins are heteroglycans based on galacturonans largely present in the primary wall of plant cells

- Hemicelluloses are a losely defined group with little strength present in cell walls intertwined with cellulose fibers

Cellulose, pectins and hemicelluloses all agregate in plant cell walls alongside the ubiquitous lignin which stiffens the wall as we shall see. Although lignin is made of CHO, and is closely associated with polysaccharides, it technically does not belong to the carbohydrate family as its monomers are not oses, but generally phenylpropanoid, and the polymerization does not involve the glycosidic bond. For this reason, lignin is presented in section 4.6 dedicated to phenolics in this chapter.

4.2.4 Other important carbohydrates

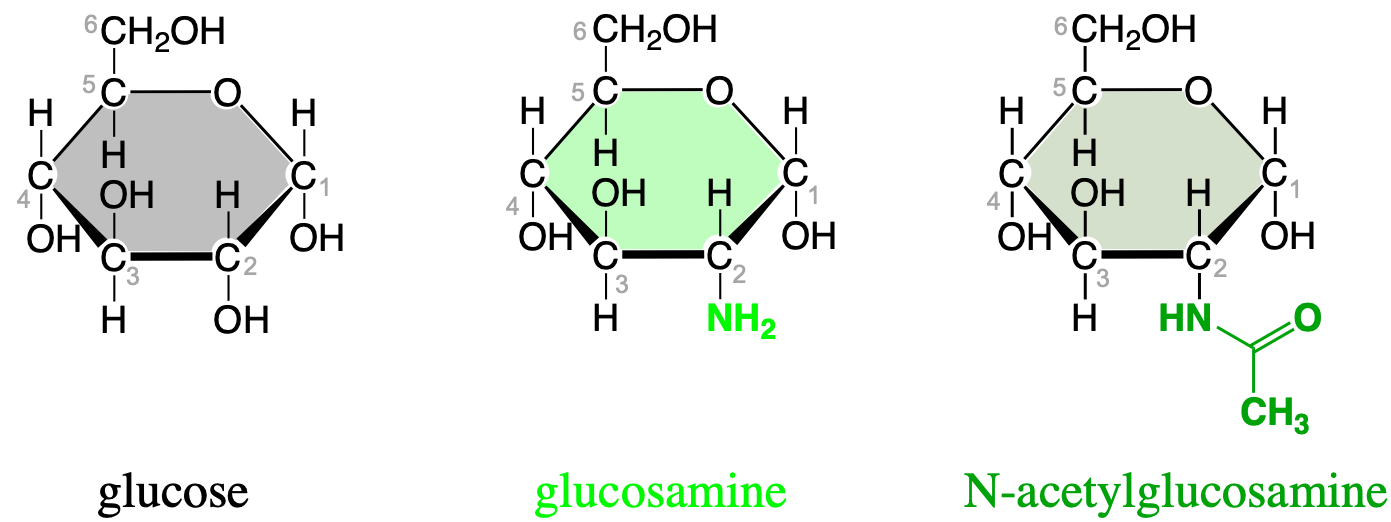

It would be erroneous to leave out some additional mono- or polyssaccharrides out as some of them play a very significant role in biology and ecology. In a way, they correspond to the exceptions that confirm or rather complete the rule. So far, we have summarized monosaccharides with the general formula (CH2O)n, to essentially be mostly C5 and C6 molecule where the average carbon is bonded to an hydroxy functional group and a hydrogen atom. And that these monosaccharides have the tendency to form 5 or 6 atom rings. Well, it turns out that on this general configuration, some of the hydroxy groups are replaced by other functional groups.

The most famous one is probably is deoxybose, as it replaces ribose, as already mentioned above and illustrated again below (Figure 4.26).

Figure 4.26: Replacement of a hydroxy group of ribose by hydrogen, effectively removing an oxygen atom or ‘deoxy-ing’ the ribose, hence the formation of deoxyribose

Several others that need mentioning are illustrated below. The first one is glucosamine where carbon number 2 has been replaced by an amine group. Glucosamine is a precursor of glycosylated proteins and lipids (glycosylated means that a sugar is linked with a protein/lipid other substituent via a glycosidic bond). When an acetyl group is added to the amine group of a glucosamine (via an amide bond), the resulting carbohydrate is called N-acetylglucosamine (Figure 4.27).

Figure 4.27: Important additional monosaccharides where the hydroxy group has been replaced by an amine and an N-acetylamine

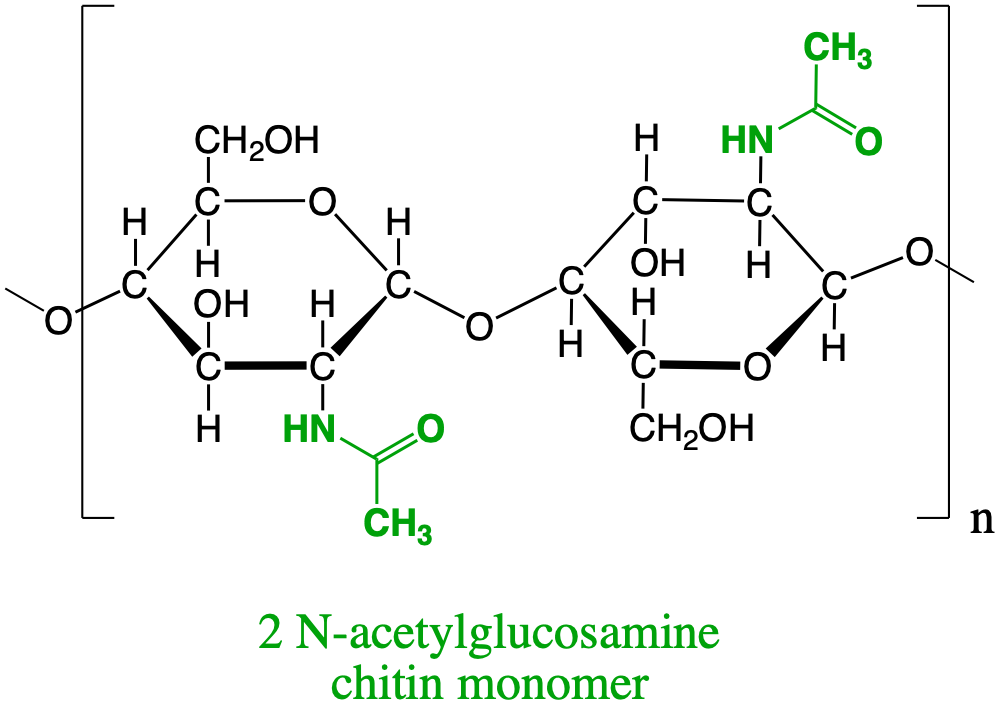

Two of these N-acetylglucosamine bonded via a glycosic bond form the monomer for chitin (Figure 4.28), i.e., the polysaccharide forming the exoskeleton of arthropods, such as crustaceans and insects, the radulae of molluscs, cephalopod beaks, and the scales of fish and lissamphibians [Wikipedia contributors (2019e); Figure 4.29].

Figure 4.28: N-acetylamine dimer forming the basis for the chitin polysaccharide that serves as exoskeleton of many invertebrates

The exoskeleton of these macroinvetebrates possesses excellent mechanical properties in terms of stiffness-todensity ratio and fracture toughness (Nikolov et al. 2011). This is explained by the microstructure of the exoskeleton, and how the chitin nanofibrils are put together (Figure 4.29).

![Exoskeleton of the American lobster (*Homarus americanus*) formed by seven levels of microstrucutures of the nanofibrils of chitin, polysaccharide of N-acetylglucosamine [@Nikolov2011-je]](pictures/chitin-lobster.jpg)

Figure 4.29: Exoskeleton of the American lobster (Homarus americanus) formed by seven levels of microstrucutures of the nanofibrils of chitin, polysaccharide of N-acetylglucosamine (Nikolov et al. 2011)

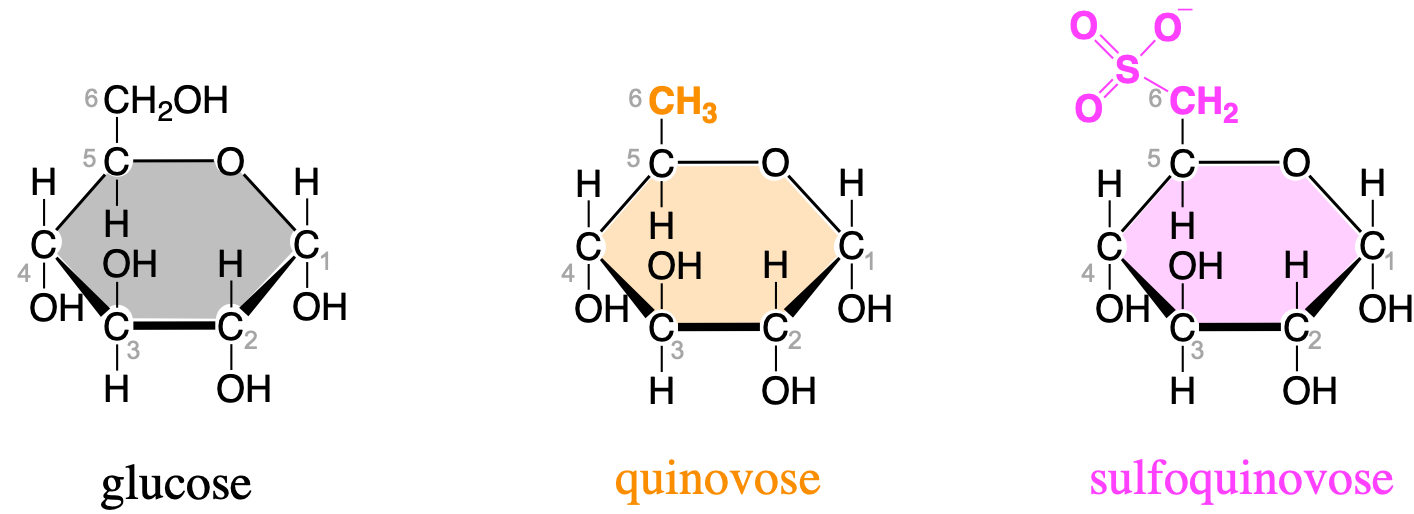

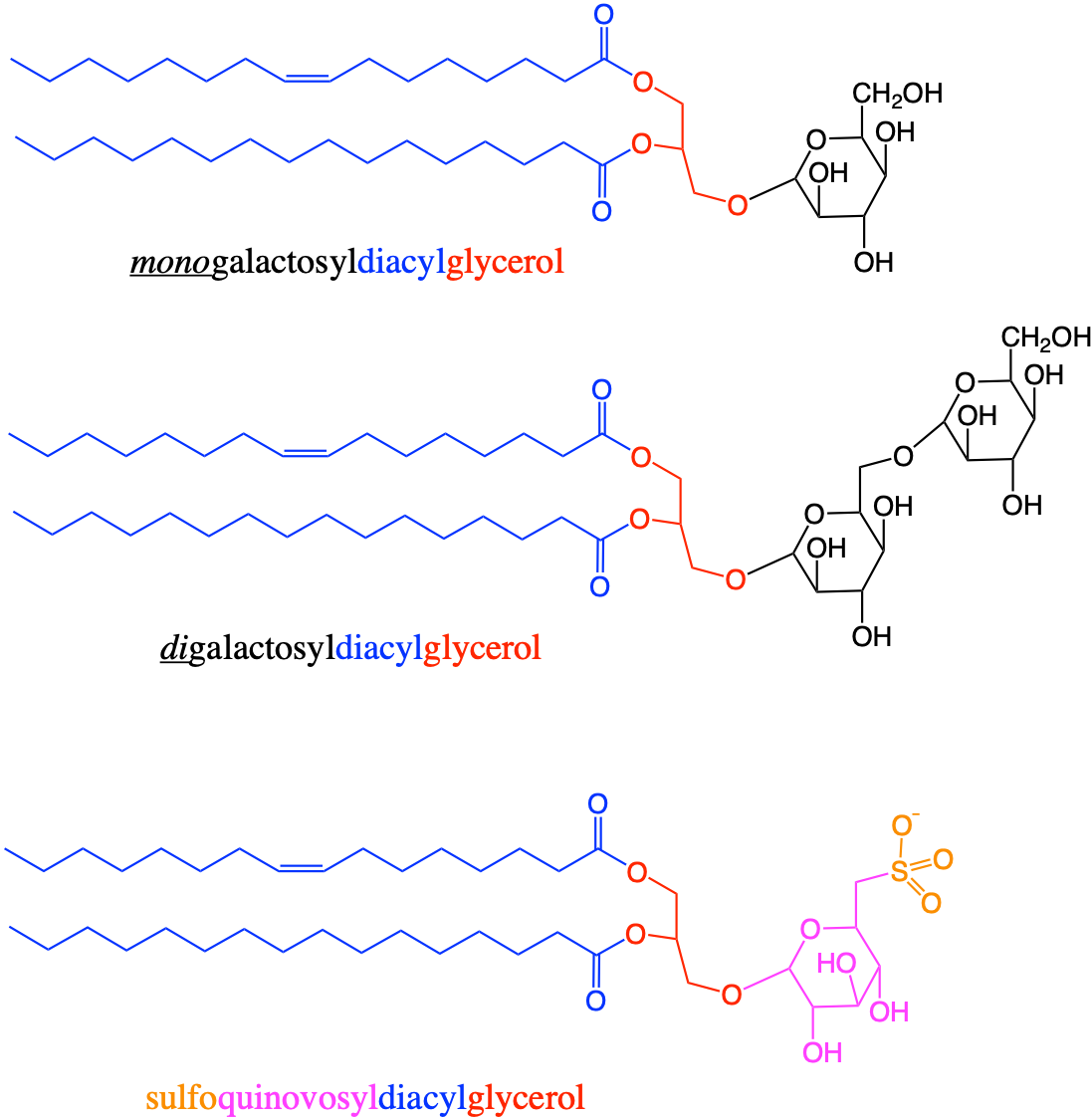

Deoxygenation of the alcohol group of carbon 6 of glucose yields quinovose or 6-deoxyglucose (Figure 4.30). The methyl radical can become sulfanated by a sulfo- radical, to yield sulfoquinovose. Sulfoquinovose is one of the backbone sugars for glycolipids that form the innermembrane of thylakoids in chloroplasts (more details in section 4.5.5.3). The molecule quinovose is a sugar moiety of the quinovin molecule, extracted from the bark of the tree of the cinchena genus in South America. The local Quechuan name is kina, and the new kina, is a quina nova, hence the word quinovin by contraction. And the sugar or ose of the quinovin is thus named a quinovose.

Figure 4.30: Glucose, quinovose, and sulfoquinovose as important monosaccharides used as building blocks for glycolipids forming the inner membranes of thylakoids in chloroplasts

Lastly, carbohydrates play a major role in the communication between cells as carbohydrates small chains are often attached to membrane proteins and lipids, in which case proteins and lipids are referred to as glycoproteins and glycolipids, respectively (more details below).

Learning outcomes

at the end of this section on carbohydrates, you should be able to:

Monosaccharides:

- Recognize that each atom has on average 4 electrons for itself, making monosaccharides the ideal molecule to store and release high energy electrons

- Recognize that the consequence is the presence of aldehyde and ketone functional groups which allow the cyclization of pentoses and hexoses

- Recognize that the release of energy can only occur when they are in the aldose chain form

- Know that their formula is (CH2O)n where 3 < n < 6, generally, and the formula of glyceraldehyde

- Recognize that small differences in the position of hydroxy, and in the cyclization of the C5 and C6 make for different monosaccharides

- Recognize that thanks to all the hydroxy groups, monosaccharides are extremely soluble in water.

- Draw a glucose molecule by heart

Disaccharides:

- Draw a glycosidic bond between consecutive glucose molecule

- Explain the concept of reducing and non-reducing sugars

- Recognize that dimers of hexoses are the energy transport molecules

- Know that sucrose is a dimer of glucose and fructose as is a non-reducing sugar

Polysaccharides

- Know that polysaccharides are generally polymers of hexoses bonded together thanks to the glycosidic bond

- Recognize that the atoms involved in the glycosidic bonds determine the type of polysaccharides

- Recognize that the energy stored on polysaccharides is not available unless the hexoses are liberated one by one or two by two (starch → maltose) from the polysaccharides chains

- Know that cellulose is the most abundant organic polymer on earth

- Know that pectins are heteroglycans based on galacturonans while hemicellulose are a losely defined group

- Recognize that chitin that forms the exoskeleton of arthropods is an polymer of N-acetylglucosamines, the latter being an aminated version of glucose

4.3 Proteins

The second molecular family we choose to present is proteins.

Etymology Corner The word proteins used in English results from the French word protéine first coined by Dutch organic and analytical chemist Gerardus Johannes Mulder in an article published in 1838 (Mulder 1838), and later translated in German as Protein in 1839. Both words are based on the ancient greek πρωτειοζ or proteioz (~primary), because Mulder thought that the ‘organic acids making protéines appeared to be the primitive or principal substance that plants prepare for herbivores, which the latter provide to the carnivores’ (Mulder 1838; Hartley 1951).

Exercise 4.3 Draw some basic Amino acids and polypeptides

In the JSME editor below, draw the molecules listed underneath. You may also render them in 3D in JSmol by going directly to JSmol demo page and click on the “JSME embedded with JSmol, for 2D⇄3D conversion” link.

Draw the simplest amino acid glycine. Its R group is H (Ans: NCC(=O)O)

Draw the alanine amino acid. Its R group is a methyl (Ans: CC(N)C(=O)O)

Draw the Phenylalanine amino acid. Its R group is a methylated phenyl group (Ans: NC(Cc1ccccc1)C(=O)O)

Draw the cysteine amino acid. Its R group is a thiol (Ans: NC(CS)C(=O)O)

Draw the lysine amino acid. Its R group is a butylamine (Ans: NCCCCC(N)C(=O)O)

Draw the serine amino acid. Its R group is a methanol (Ans: NC(CO)C(=O)O)

Draw the valine amino acid. Its R group is an isopropyl (Ans: CC(C)C(N)C(=O)O)

Draw the polypeptide valine-glycine-phenylalanine-valine (Ans: CC(C)C(N)C(=O)NCC(=O)NC(C(=O)NC(C(=O)O)C(C)C)c1ccccc1)

Draw the polypeptide valine-phenylalanine-glycine-valine (Ans: CC(C)C(N)C(=O)NC(C(=O)NCC(=O)NC(C(=O)O)C(C)C)c1ccccc1)

Proteins correspond to single, or assemblages of, polymers of amino acids referred to as polypeptide chains.

This chapter is still under construction

4.4 Nucleic Acids and Nucleotides

The third molecular family we choose to present are Nucleic Acids. The term nucleic acid is the overall name for the DeoxyriboNucleic Acid (DNA) and the RiboNucleic Acid (RNA). DNA and RNA carry the genetic code and are present in every living cell on this planet (viruses seem to have some variations on that). Nucleic acids are polymers of nucleotides, and as such are polynucleotides. Nucleic acids are unbranched molecules that generally are very large, and in fact the longest among all macromolecules, accounting up to 247 million monomers in a human chromosome (Wikipedia contributors 2021a).

It was Friedrich Miescher, Swiss physician and biologist who first isolated what he called nuclein from nuclei of white blood cells he had access to from pus-coated patient bandages (Miescher 1871). Miescher came across this “substance from the cell nuclei that had chemical properties unlike any protein, including a much higher phosphorous content and resistance to proteolysis (protein digestion). […] Miescher’s discovery of nucleic acids was unique among the discoveries of the four major cellular components (i.e., proteins, lipids, polysaccharides, and nucleic acids) in that it could be dated precisely… [to] one man, one place, one date” (“Discovery of DNA Double Helix: Watson and Crick,” n.d.).

Nucleic acids are made of the C,H,O,N, and P atoms with a relatively high concentration of N and P compared to any other molecular family. This suggests that the combined and concentrated presence of N and P makes for very special molecules.

4.4.1 Nucleotides as monomers of nucleic acids

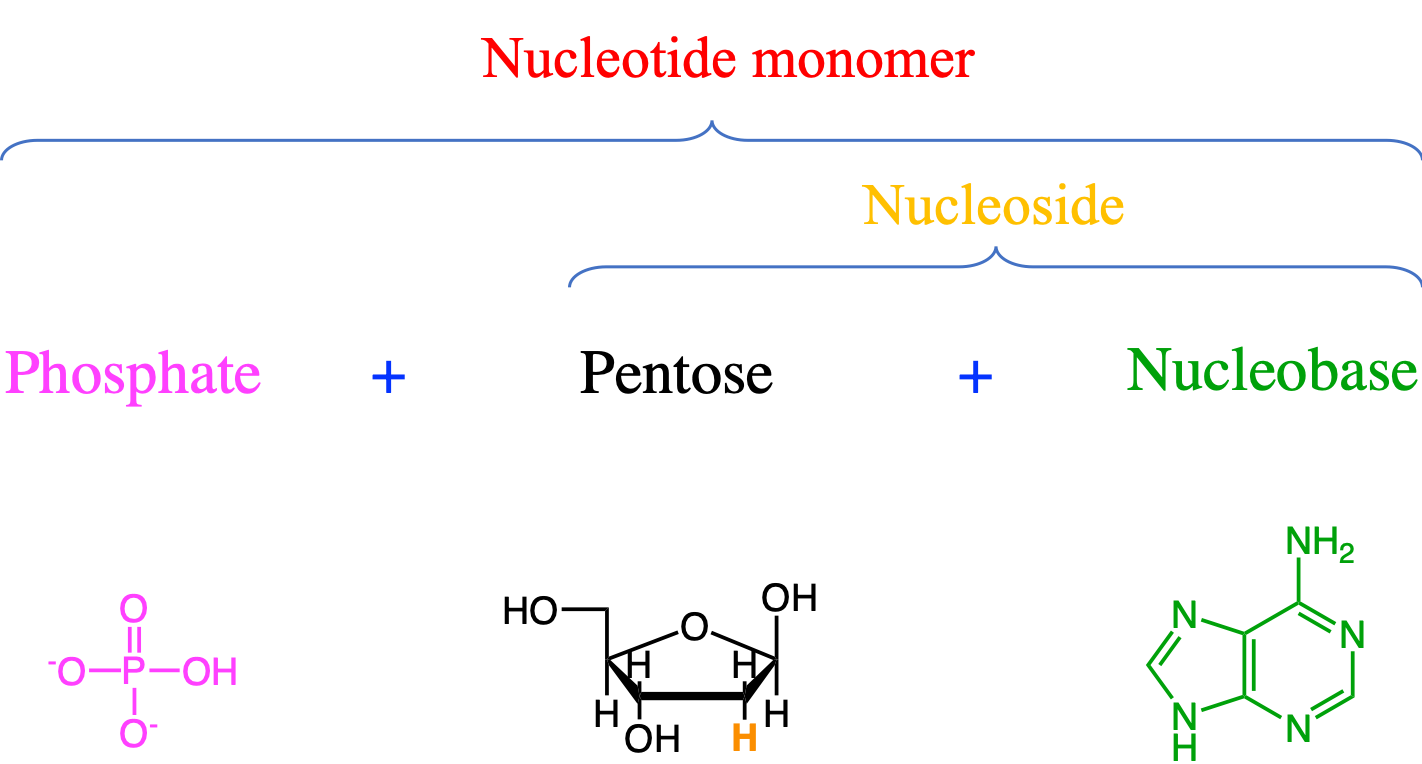

DNA and RNA are polymers of four nucleotide monomers. Each of them is made of three moeities bonded together: a phosphate, a pentose, and a nucleobase, the latter sometimes referred to as a nitrogenous base (Figure 4.31). The names of the nucleobases (Adenine, Guanine, Cytosine, Thymine - for DNA, and Uracil - for RNA) are sometimes used to describe the nucleotide itself, which might be confusing…

Figure 4.31: The basis structure of the generic monomer of a nucleic acid is made of phosphate, pentose, and nucleobase moieties. The nucleobase in the figure is Adenine, and the pentose is a deoxyribose

It is important to be able to recognize the differences between the nucleobases, nucleosides, and nucleotides. Nucleobases or otherwise named nitrogenous bases because of the large density of nitrogen atoms are divided into purines (5 N atoms for 3-4 C atoms) and pyrimidines (3 N atoms for 4-5 C atoms). Purines and pyrimidines are heteroarenes (see Figure 3.10 and section 3.1.3), that have aromatic cycles, where some of the carbon atoms have been replaced by nitrogen atoms. Adenine, Guanine, and Cytosine are common to DNA and RNA, while Thymine is only present in DNA, and Uracil only present in RNA. Both purines and pyrimidines are ‘flat’ molecules, which can be paired together thanks to hydrogen bonds (details below).

[@Blausencom_staff2014-gi]](pictures/Nucleobases.png)

Figure 4.32: The purines and pyrimidines form the nucleobase moieties of nucleotide monomers. Because of the aromatic nature of these moieties, the nucleobases are flat, allowing for pairing using hydrogen bonds After BruceBlaus, CC BY 3.0 (Blausen.com staff 2014)

The condensation reaction between a nucleobase and a pentose on the 1’ carbon results in a nucleoside (Figure 4.33). To differentiate between the carbons of the nucleobases and those of the pentose, geneticists have added a “prime” or apostrophy next to the carbon number, hence the 1’ Figure 4.33.

Figure 4.33: The condensation reaction between a pentose and a nucleobase on the carbon 1’ corresponds to an N-glycosidic bond and results in the formation of a nucleoside. The nucleobase in the figure is Adenine, and the pentose is a deoxyribose

The condensation between a nucleoside and a phosphate moiety forms a nucleotide (Figure 4.34). The bond between the 5’ carbon of the pentose with phosphate is a phosphoester bond.

Figure 4.34: The condensation reaction between a phosphate moiety and a nucleoside results in the formation of a nucleotide monomer. The bond between the phosphate and the nucleoside moieties is a phosphoester bond. The nucleobase in the figure is Adenine, and the pentose is a deoxyribose

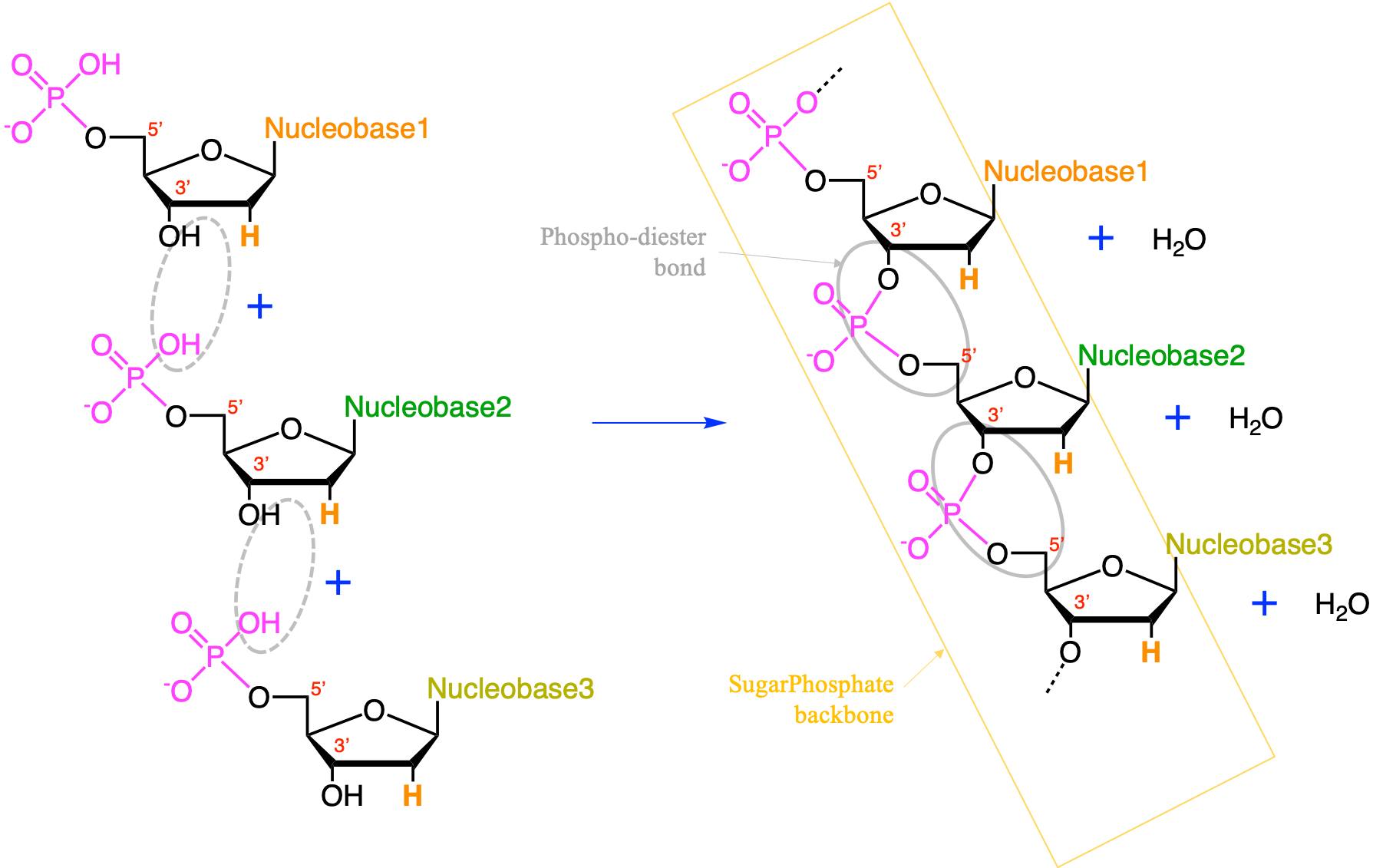

Nucleic acids are formed by the polymerization of nucleotide monomers. This polymerization is made possible thanks to the condensation between the phosphate moeity of one nucleotide with the hydroxy on 3’ of the pentose moiety of another nucleotide (Figure 4.35). The polymerization occurs at the 3’ end, of in the case of Figure 4.35 by adding a nucleotide at the bottom. The phosphate moiety in a nucleic acid chain is bonded to 2 pentose moieties and this bond is referred to as a phospho-diester bond. This bond is crucial and extremely rigid and provide what is referred to as the sugar-phosphate backbone.

Figure 4.35: The condensation reaction between consecutive nucleotides between the phosphate moiety and the carbon 3’ results in the formation of a nucleic acids. The bond between the phosphate moiety and the two pentoses is a phospho-diester bond. The phosphate-pentose chain held togeter by the phospho-diester bond is referred to as the sugar-phosphate backbone. The pentose is a deoxyribose

In both RNA and DNA, the sugar-phosphate backbone results in the 3D formation of α-helix molecules. In Figure 4.36, the sugar-phosphate backbone has been illustrated as a ribbon. Notice the phosphate moeiety on the outside of the ribbon forcing the nucleoside and thus the nitrogenous bases to point into the helix and stacking on top of each other. It takes about 10 polynucleotides to make a full circle.

Figure 4.36: Illustration of the double-helix double-stranded molecule of DNA with 10 nucleotides polymerized for each strand

4.4.2 DNA and RNA

The DeoxyriboNucleic Acids (DNA) and the RiboNucleic Acids (RNA) have several fondamental differences:

- the pentose for RNA is a Ribose, and for DNA it is a Deoxyribose (Figure 4.31 and 4.37)

- one of the pyrimidine nucleobases is only found in DNA, i.e., Thymine, and the other is only found in RNA, and that is Uracil. The difference between the two is one methyl group missing on Uracil (Figure 4.32 and 4.38)

- DNA is a double-stranded molecule, while RNA is single-stranded (Figure 4.38)

Figure 4.37: Replacement of a hydroxy group of ribose by hydrogen, effectively removing an oxygen atom or ‘deoxy-ing’ the ribose, hence the formation of deoxyribose

](pictures/DNA-RNA-EN.png)

Figure 4.38: Differences between RNA (left) and DNA (Right) illustrating the single-stranded structure of RNA and the Uracil nucleobase, vs. the double-stranded structure of DNA and the thymine nucleobase that replaces the uracil. by Roland1952, CC BY-SA 3.0

The double helix […] double-stranded DNA, […] is composed of two linear strands that run opposite to each other, or anti-parallel, and twist together. Each DNA strand within the double helix is a long, linear molecule made of smaller units called nucleotides that form a chain. […] The two helical strands are connected through interactions between pairs of nucleotides, also called base pairs. Two types of base pairing occur: nucleotide A pairs with T, and nucleotide C pairs with G (“Double Helix,” n.d.).

![Two hydrogen bonds connect T to A; three hydrogen bonds connect G to C. The sugar-phosphate backbones (grey) run anti-parallel to each other, so that the 3’ and 5’ ends of the two strands are aligned. Figure and caption from [@noauthor_undated-pi]](pictures/DNA-double-helix-nature.jpg)

Figure 4.39: Two hydrogen bonds connect T to A; three hydrogen bonds connect G to C. The sugar-phosphate backbones (grey) run anti-parallel to each other, so that the 3’ and 5’ ends of the two strands are aligned. Figure and caption from (“Discovery of DNA Double Helix: Watson and Crick,” n.d.)

A unique pairing between Adenine (A) and Thymine (T) nucleotides, and between Guanine (G) and Cytosine (C) nucleotides in DNA, and, between Adenine and Uracil (U) during RNA transcription is at the core of the replication of the genetic code and its transcription into the synthesis of proteins. The pairing only occurs between a pyrimidine and a purine bases. This is associated with the space available within the double helix (20 Å): not enough for two purines to fit within the helix and too much space for two pyrimidines to get close enough to each other to form hydrogen bonds.

The unique pairing between A and T, C and G, and A and U is possible thanks to:

- the sugar-phosphate backbone structure which leads the nucleotide bases to point into the helix for a diameter of 20 Å leaving enough room for a purine and a pyrimidine moeities to face each other at the center (Figure 4.36)

- the planar structure of the nitrogenous bases due to the aromatic rings, and the location of functional groups that place the amine and carbonyl groups outward on a same plane (Figure 4.36 and 4.32)

- the high electronic density associated with the lone pairs of electrons on the oxygen of the carbonyl groups and the nitrogen of the amine groups that open the possibility for the creation of hydrogen bonds between (Figure 4.39)

- C=O····H-N

- N-H····N

This results in the possibility of forming of three hydrogen bonds between C and G, while only two hydrogen bonds can occur between A and T, and A and U, hence the unique pairing described above. This also results in the fact that the two strands of the DNA molecule are a mirror image of each other although they run opposite or anti-parallel to each other.

4.4.2.1 Quick recall on DNA replication

It is impossible to present nucleic acids structure and not presenting any of their function, although this is objectively secondary as the main goal of this chapter is to direct why living organisms need nutrients, and in what molecules these atom eventually end up. The structure of DNA is all geared towards the replication and the transcription of the genetic code. The goal here is not to give an in depth course on replication, but provide enough of the details.

In simple terms, replication involves use of an existing strand of DNA as a template for the synthesis of a new, identical strand (Pray 2008).

For this to happen the double helix needs first to be unwinded and maintained as such. Then DNA polymerases can add deoxynucleotides at the 3’ end.

This chapter is still under construction

Exercise 4.4 Draw some basic Nucleobases and nucleotides

In the JSME editor below, draw the molecules listed underneath. You may also render them in 3D in JSmol by going directly to JSmol demo page and click on the “JSME embedded with JSmol, for 2D⇄3D conversion” link.

Purine nucleobases

Draw the adenine nucleobase.

(Ans: C/1=N/C2=C(C(N)=N1)/N=C)

(Ans: C/1=N/C2=C(C(N)=N1)/N=C)Draw the guanine nucleobase.

(Ans: C1(/N)=N=C(C(=O)N1)=C/N2)

(Ans: C1(/N)=N=C(C(=O)N1)=C/N2)

Pyrimidine nucleobases

Draw the cytosine nucleobase.

(Ans: C1(=O)/N=C(N)=C/N1)

(Ans: C1(=O)/N=C(N)=C/N1)Draw the thymine nucleobase.

(Ans: C1(=O)NC(=O)/C(C)=C)

(Ans: C1(=O)NC(=O)/C(C)=C)Draw the uracil nucleobase.

(Ans: C1(=O)NC(=O)/C=C)

(Ans: C1(=O)NC(=O)/C=C)

Nucleotides: Nucleoside monophosphates

- Draw the deoxyadenosine monophosphate, i.e., the DNA nucleotide monomer that contains the adenine nucleobase (Ans:C1C(C(OC1N2C=NC3=C(N=CN=C32)N)COP(=O)(O)O)O)

https://www.britannica.com/science/acid

Nucleotide, any member of a class of organic compounds in which the molecular structure comprises a nitrogen-containing unit (base) linked to a sugar and a phosphate group. The nucleotides are of great importance to living organisms, as they are the building blocks of nucleic acids, the substances that control all hereditary characteristics.

In the two families of nucleic acids, ribonucleic acid (RNA) and deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA), the sequence of nucleotides in the DNA or RNA codes for the structure of proteins synthesized in the cell. The nucleotide adenosine triphosphate (ATP) supplies the driving force of many metabolic processes. Several nucleotides are coenzymes; they act with enzymes to speed up (catalyze) biochemical reactions.

The nitrogen-containing bases of nearly all nucleotides are derivatives of three heterocyclic compounds: pyrimidine, purine, and pyridine. The most common nitrogen bases are the pyrimidines (cytosine, thymine, and uracil), the purines (adenine and guanine), and the pyridine nicotinamide.

Nucleosides are similar to nucleotides except that they lack the phosphate group. Nucleosides themselves rarely participate in cell metabolism.

Adenosine monophosphate (AMP) is one of the components of RNA and also the organic component of the energy-carrying molecule ATP. In certain vital metabolic processes, AMP combines with inorganic phosphate to form ADP (adenosine diphosphate) and then ATP. The breaking of the phosphate bonds in ATP releases great amounts of energy that are consumed in driving chemical reactions or contracting muscle fibres. Cyclic AMP, another nucleotide, is involved in regulating many aspects of cellular metabolism, such as the breakdown of glycogen.

A dinucleotide, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD), participates in many oxidation reactions as an electron carrier, along with the related compound nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADP). These substances act as cofactors to certain enzymes.

We have not mentioned this molecule just yet because it is a complicated molecule. Yet, it plays a crucial role in many catalytic reactions

Structure of coenzyme A: 1: 3′-phosphoadenosine. 2: diphosphate, organophosphate anhydride. 3: pantoic acid. 4: β-alanine. 5: cysteamine. By NEUROtiker - Own work, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1555659

This chapter is still under construction

4.5 Lipids

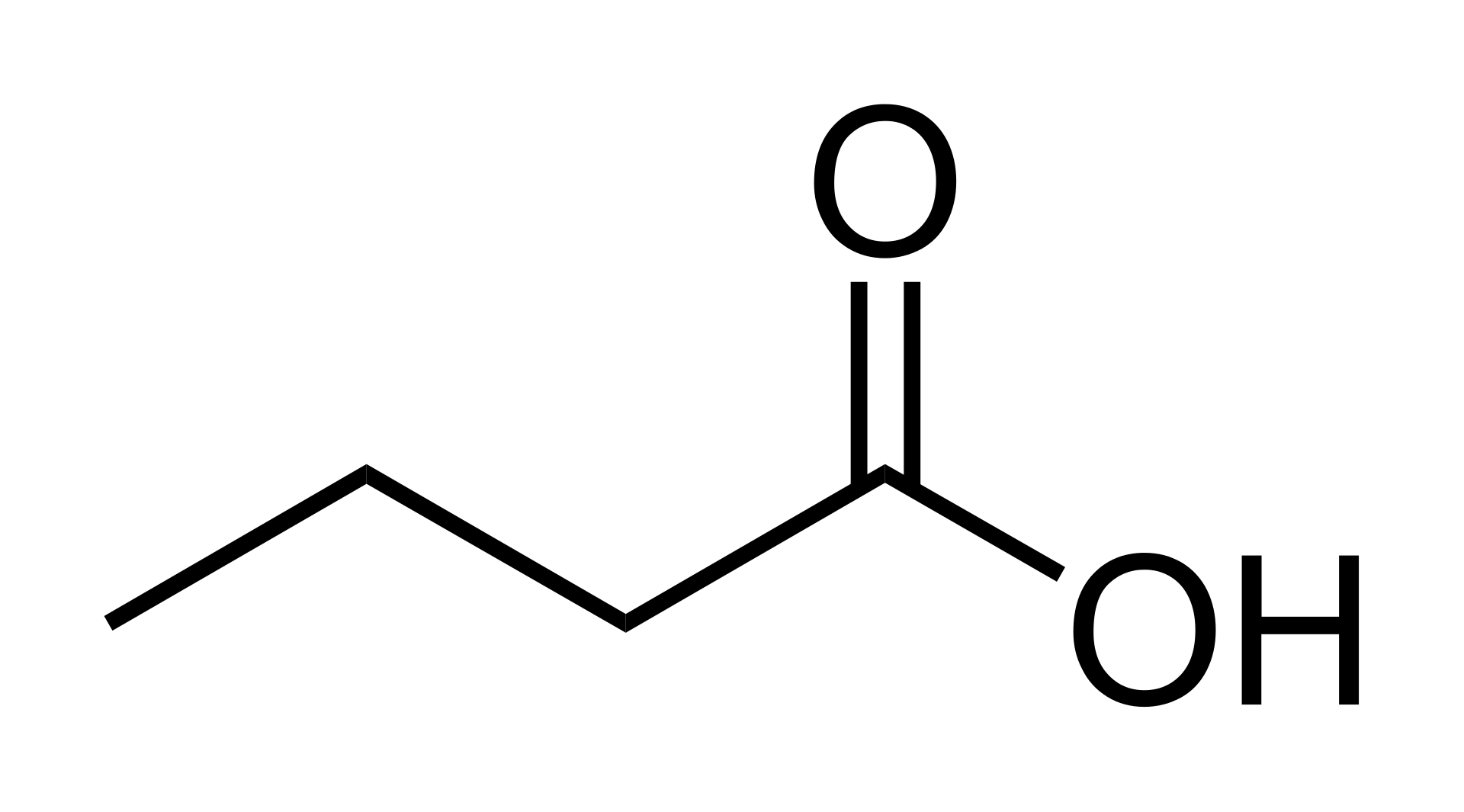

Lipids are fatty acids and their derivatives, and substances related biosynthetically or functionally to these compounds (W. W. Christie 1987).

This is the best concise and satisfying definition! The scientific term “lipid” comes from the Greek “lipos” which referred to animal fat or vegetable oil. Lipids are mainly made of C and H atoms, but do also contain O, N, and P. So it is important to remember that lipids are made of CHONP. Lipids are a very heterogeneous group of molecules and are defined in part from their propensity to be soluble in non-polar solvents (no net dipole as a result of the opposing charges in the solvent molecules). In other words, lipids do not (or not easily) dissolve in water.

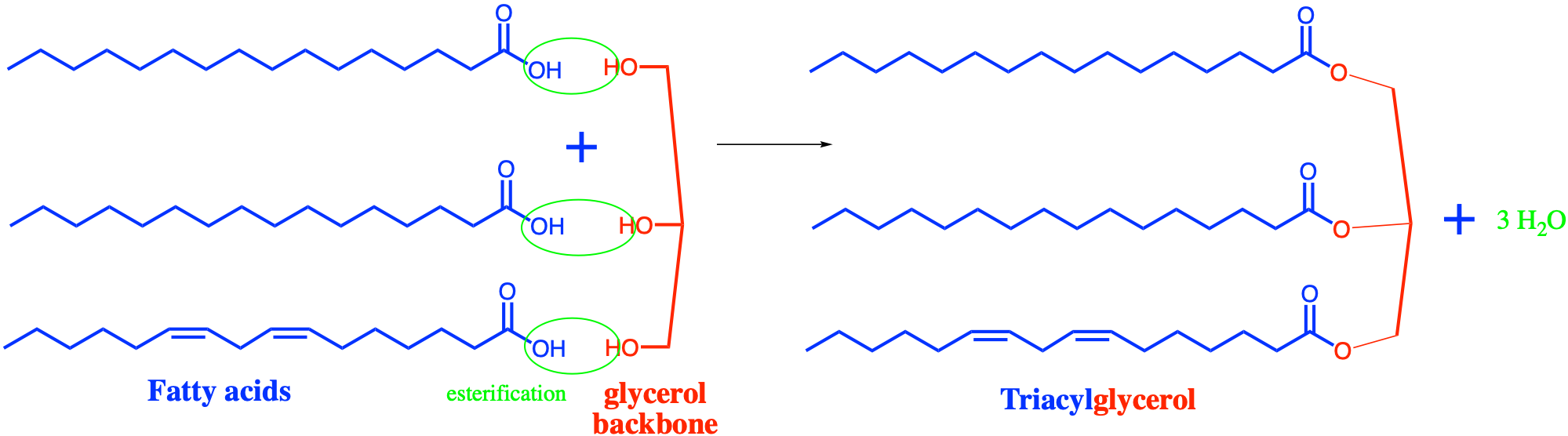

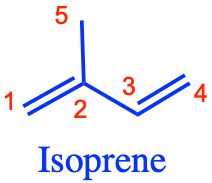

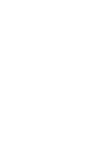

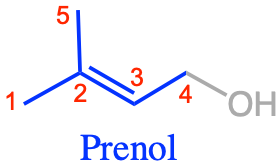

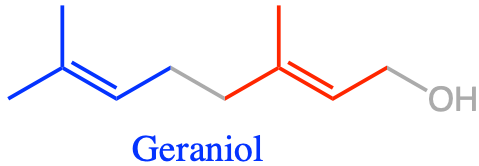

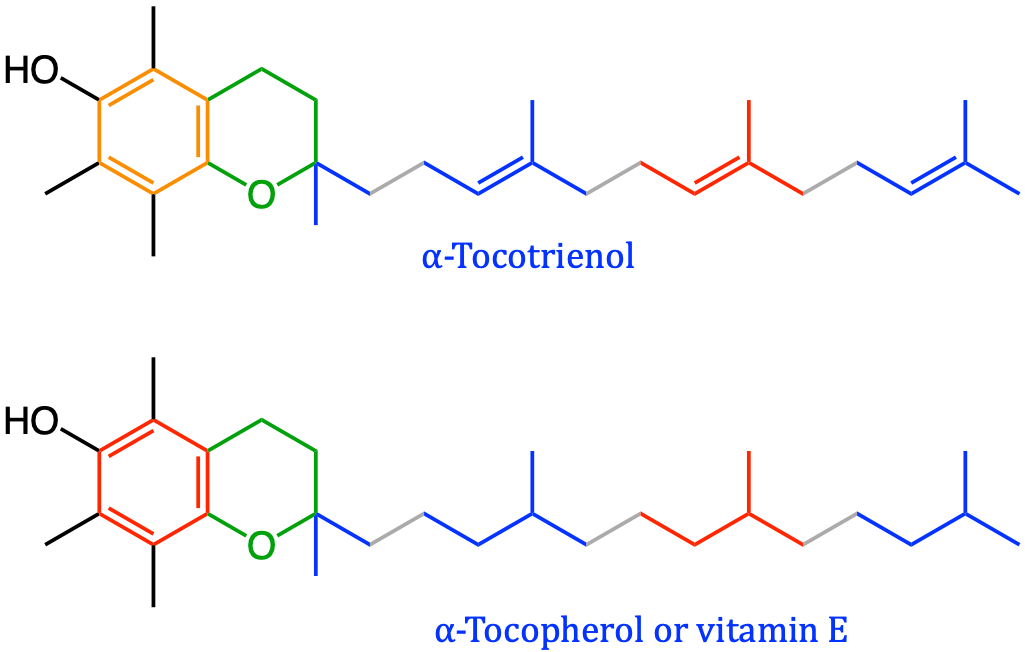

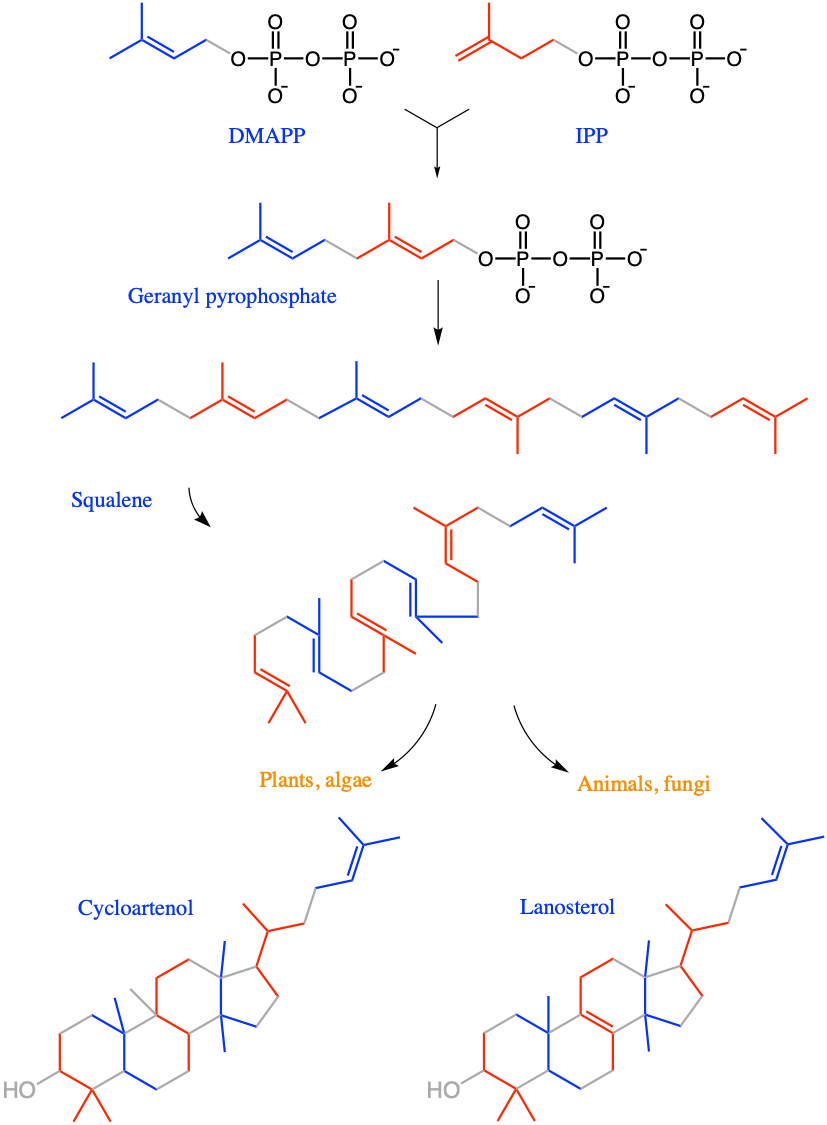

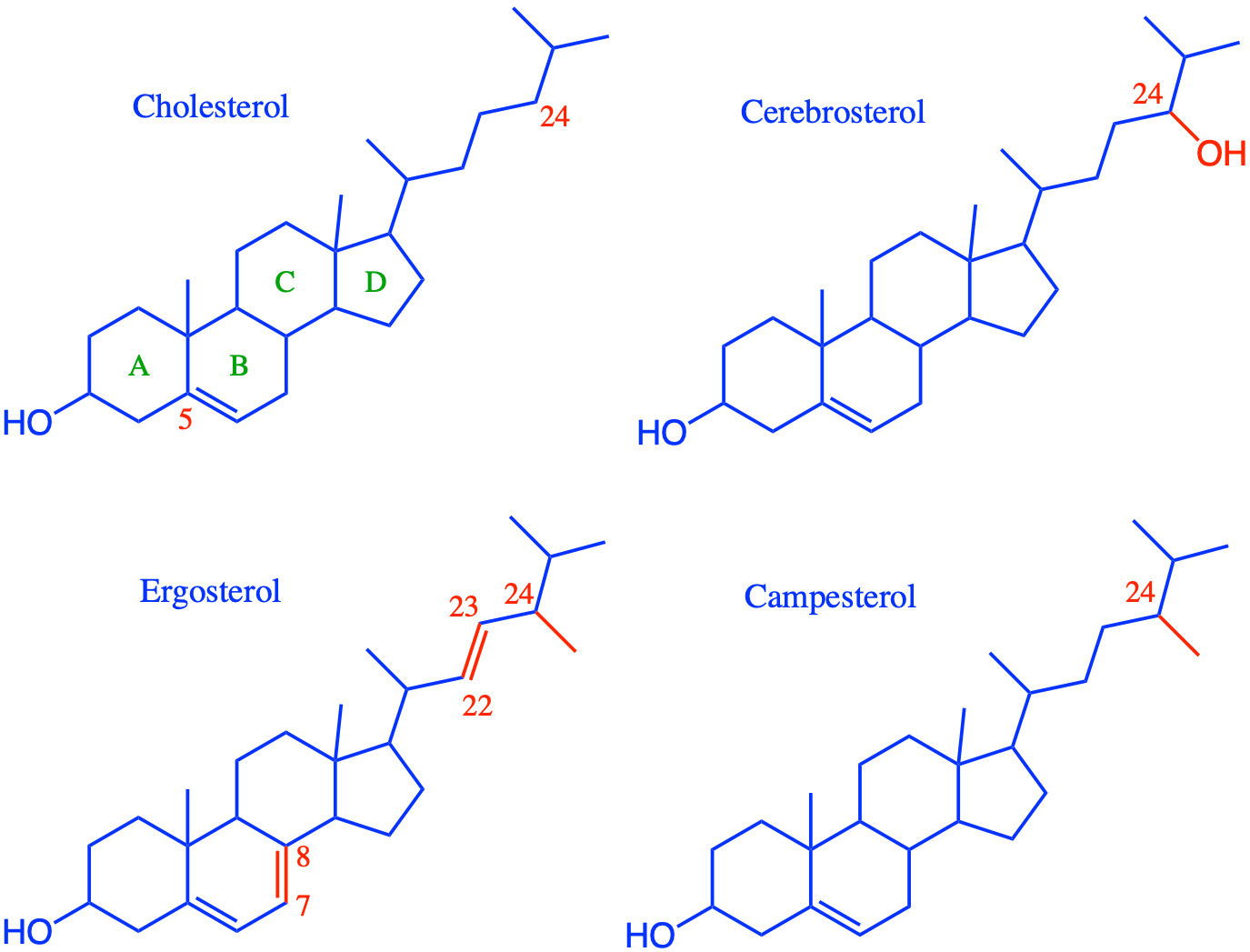

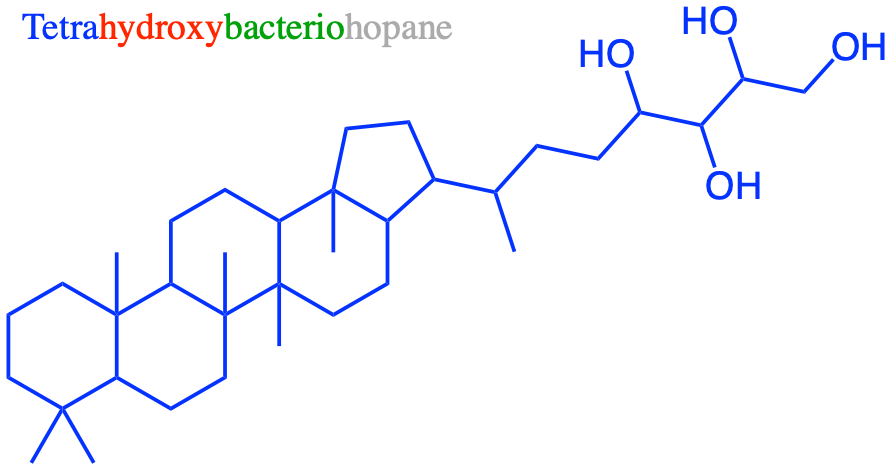

Contrary to carbohydrates, proteins, or nucleic acids, lipids are not obvious polymers of identified and clearly defined monomers. Rather, lipids are assemblages of well identified building blocks and backbones bonded together with ester, ether, and amide bonds. There are two main types of building blocks resulting in two major types of lipids: lipids built from fatty acid blocks (acyl groups) and lipids based from isoprene building units (ringed or not isoprene groups). Because there is no polymerization, lipids are relatively small molecules compared to polysaccharides, proteins, or nucleic acids.

Figure 4.40: Common everyday ingredients containing lipids. (obtained from http://blesslaboratory.com/index.php/services/oil

The carbons of lipids are generally a lot more reduced (have more electrons for themselves) than the ones of carbohydrates. For the latter, there are just about as many oxygen atoms as there are carbons, as a legacy of how they are formed during photosynthesis (details in chapter 6). Because of the number of oxygen atoms and their reactivity, carbohydrates are only able to form relatively short 5 and 6 carbon monomers, which tend to readily assemble into rings. Polymerization is what allows carbohydrates to form very large molecules.

Lipids aliphatic chains have almost no oxygen atoms instead, and always strategically located near the ends of the chains. Consequently, the carbons of the hydrocarbon chains are not as prompt to react together. The result is that it becomes possible to have longer hydrocarbon molecules (commonly C16 to C22, compared to C5 and C6 carbohydrates). The aliphatic chains are relatively chemically inert and interact together by low level van der Waals forces. These long aliphatic chains are the reasons for the mostly hydrophobic character of lipids (Figure 4.40).

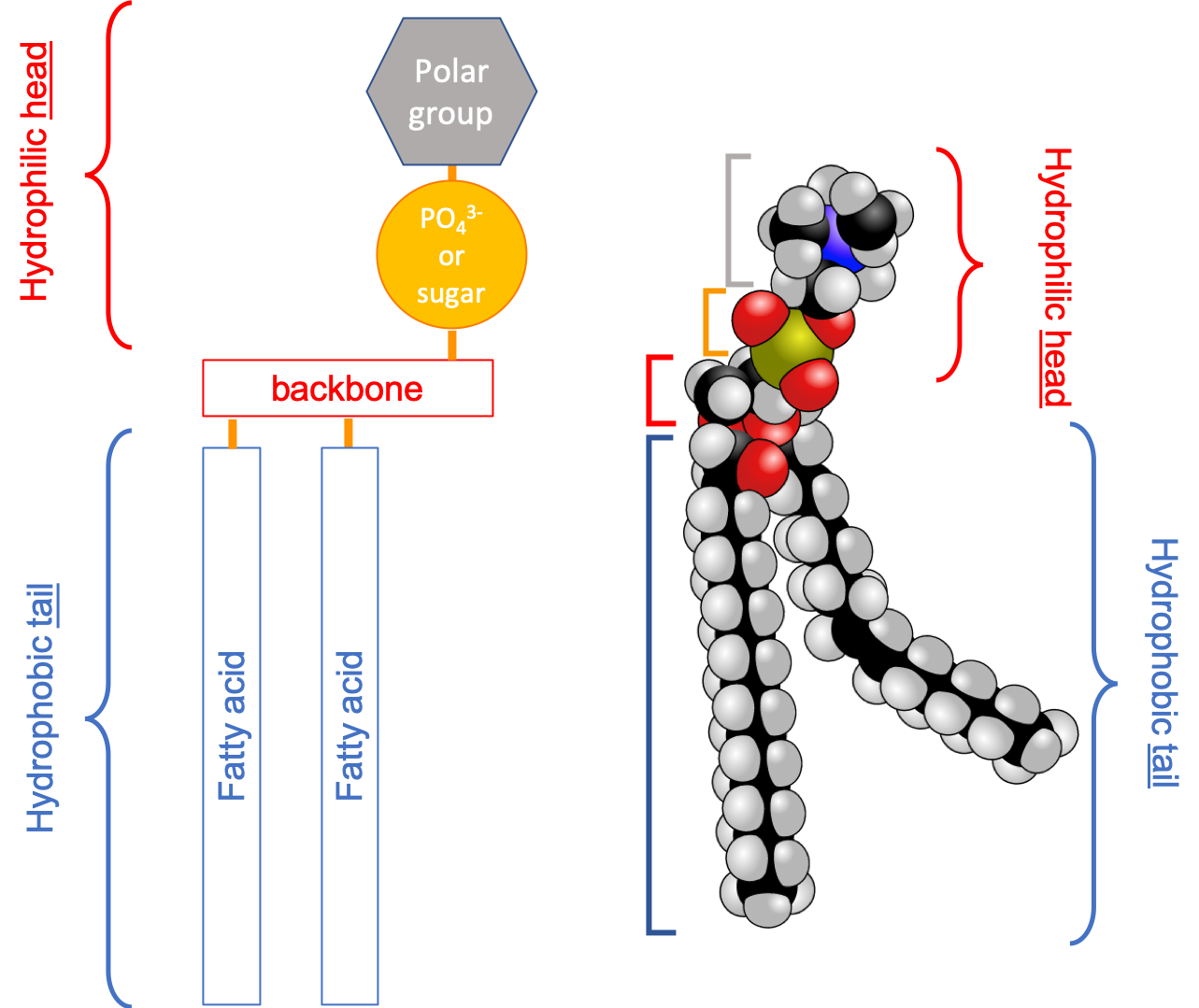

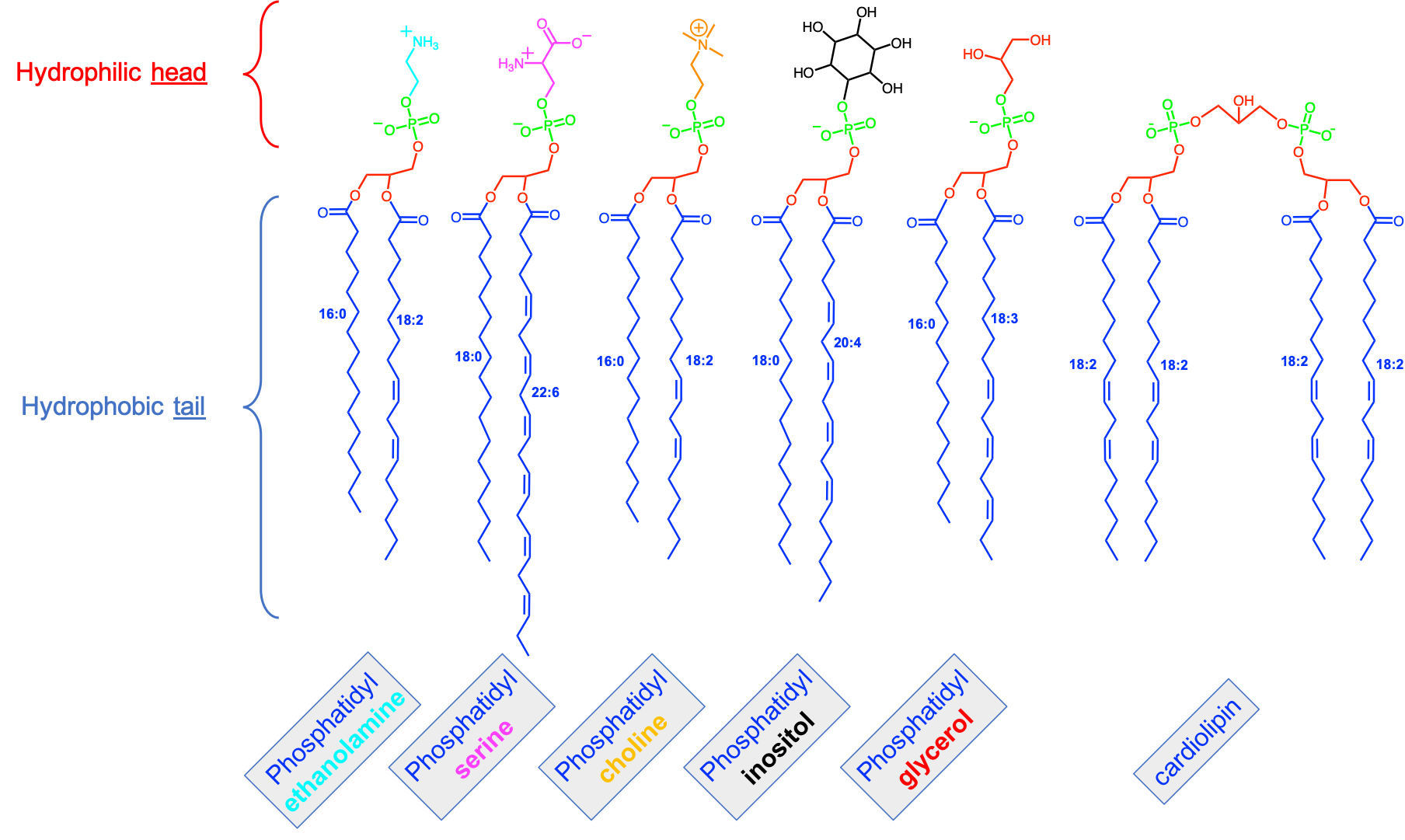

However, the fatty acid-based lipids are amphipathic (also referred to as amphiphilic), i.e., that they have both hydrophilic and hydrophobic ends. The hydrophobic end or hydrophobic tail corresponds to the long aliphatic chain of the fatty acid residue. The hydrophilic end or hydrophilic head is associated with the other building blocks made of ionic and polar groups that include ester and amide bonds, the backbone, and other polar radicals (details below). The amphiphilic nature of some lipids allows them to form structures such as vesicles, multilamellar/unilamellar liposomes, or membranes in an aqueous environment (Wikipedia contributors 2019a).

Overall, lipids function as essential structural components of membranes, as signalling molecules, as chemical identifiers of specific membranes and as energy storage molecules (Meer, Voelker, and Feigenson 2008). Thousands of lipid molecules have been listed and an entire scientific discipline called lipidomics is dedicated to lipids structure and function! Rigorous classifications have been proposed (e.g., Fahy et al. (2005), Fahy et al. (2009)), and gateways on lipid research and updates are available (e.g., lipidmaps). Our goal here is to present enough of what lipids are and do.

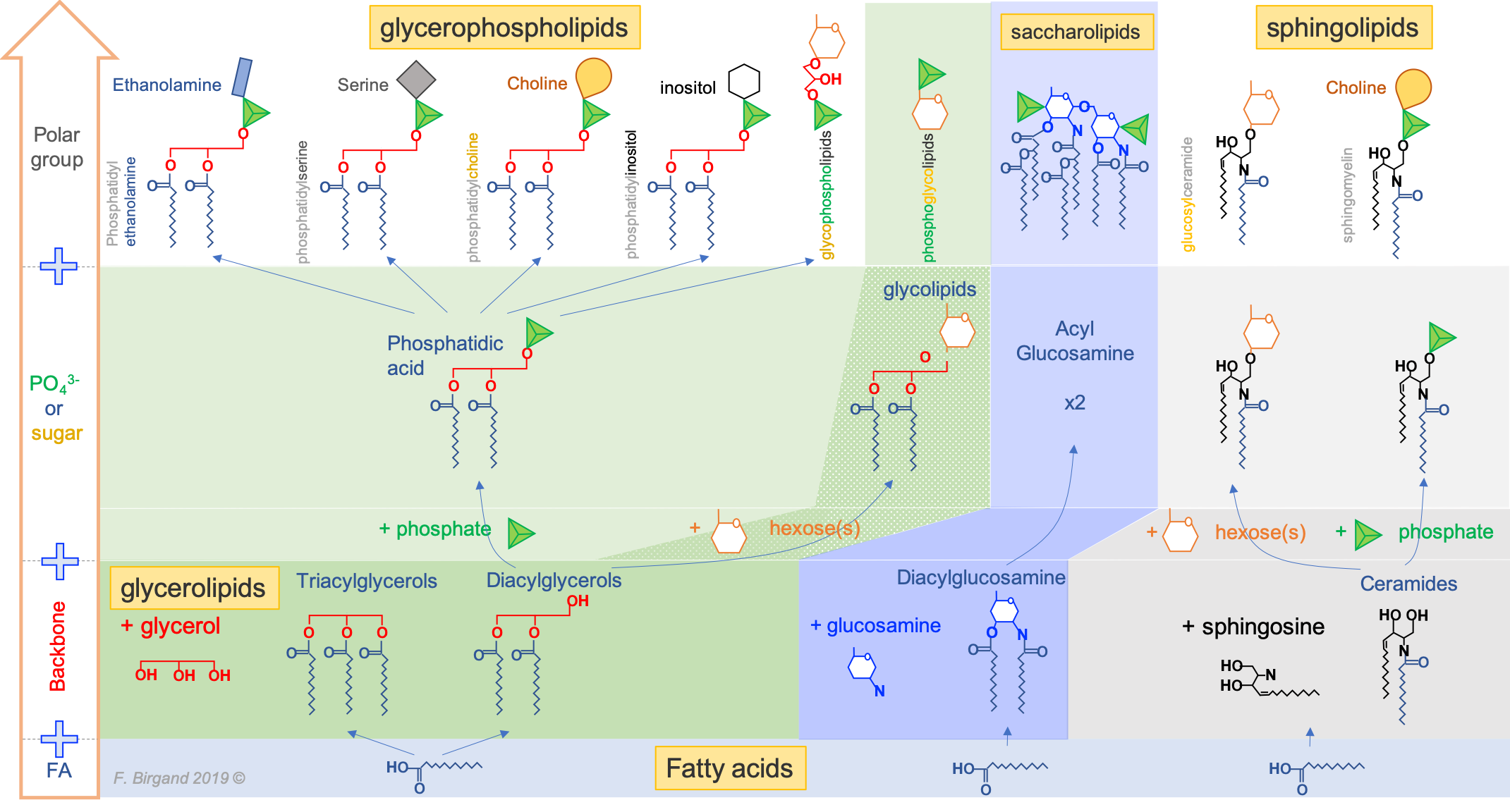

Overall lipids may be divided into eight categories: fatty acids, glycerolipids, glycerophospholipids, sphingolipids, saccharolipids, and polyketides (derived from condensation of acyl subunits); and sterol lipids and prenol lipids (derived from condensation of isoprene subunits) (Wikipedia contributors 2019a)

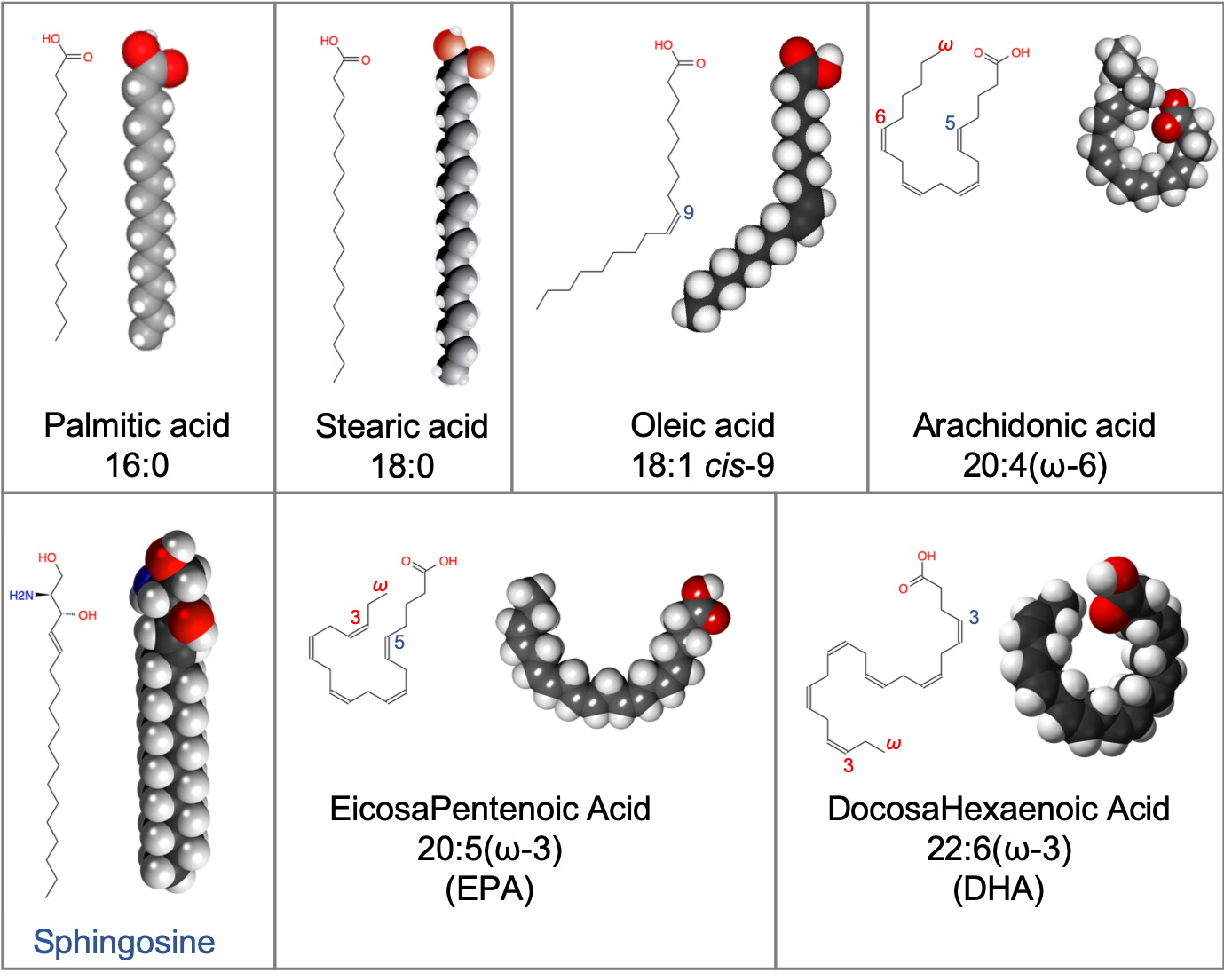

4.5.1 Overview of fatty acid- or acyl-based lipids

In this category, are included fatty acids, glycerolipids, glycerophospholipids, saccharolipids, and sphingolipids. They all have in common the presence of long aliphatic carbon chains forming ‘tails’ of the molecules. The average carbon of a fatty acid chain is a methylene (-CH2-) such that each carbon atom has 6 electrons for itself (Figure 4.41). Consequently, lipids are, among the macromolecules, those which can store and release the most energy per carbon atom!

Figure 4.41: Electron allocation of a generic fatty acyl group (CH2)n. The group -CH2- is referred to as a methelene group

Lipids share with nucleic acids the ‘building block’ structure, in that they are built of identified building blocks. The quintessential acyl-based lipid is made of two fatty acids forming the hydrophobic tail end, a backbone, a phosphate or hexose, and a polar group. The two latter building blocks form the hydrophilic head, which tends to be a lot shorter than the hydrophobic end as illustrated in Figure 4.42 below.

Figure 4.42: Schematic of the quintessential fatty acid based lipid illustrating the amphipathic nature, and the different building blocks

From this simple construction, thousands of acyl-based lipid molecules exist following a wide variation on the fatty acids themselves, the three types of backbones, and on the polar groups (nature and number). And there are lots of exception to this general rule (e.g., Fahy et al. 2005, 2009). Nonetheless, Figure 4.43 summarizes how acyl-based lipids are constructed and how some of the classification has been derived. It reads from the bottom to top.

The first stage of molecules having only one of the building blocks are the fatty acids. There are so many of them that they are classified as a lipid group by themselves.

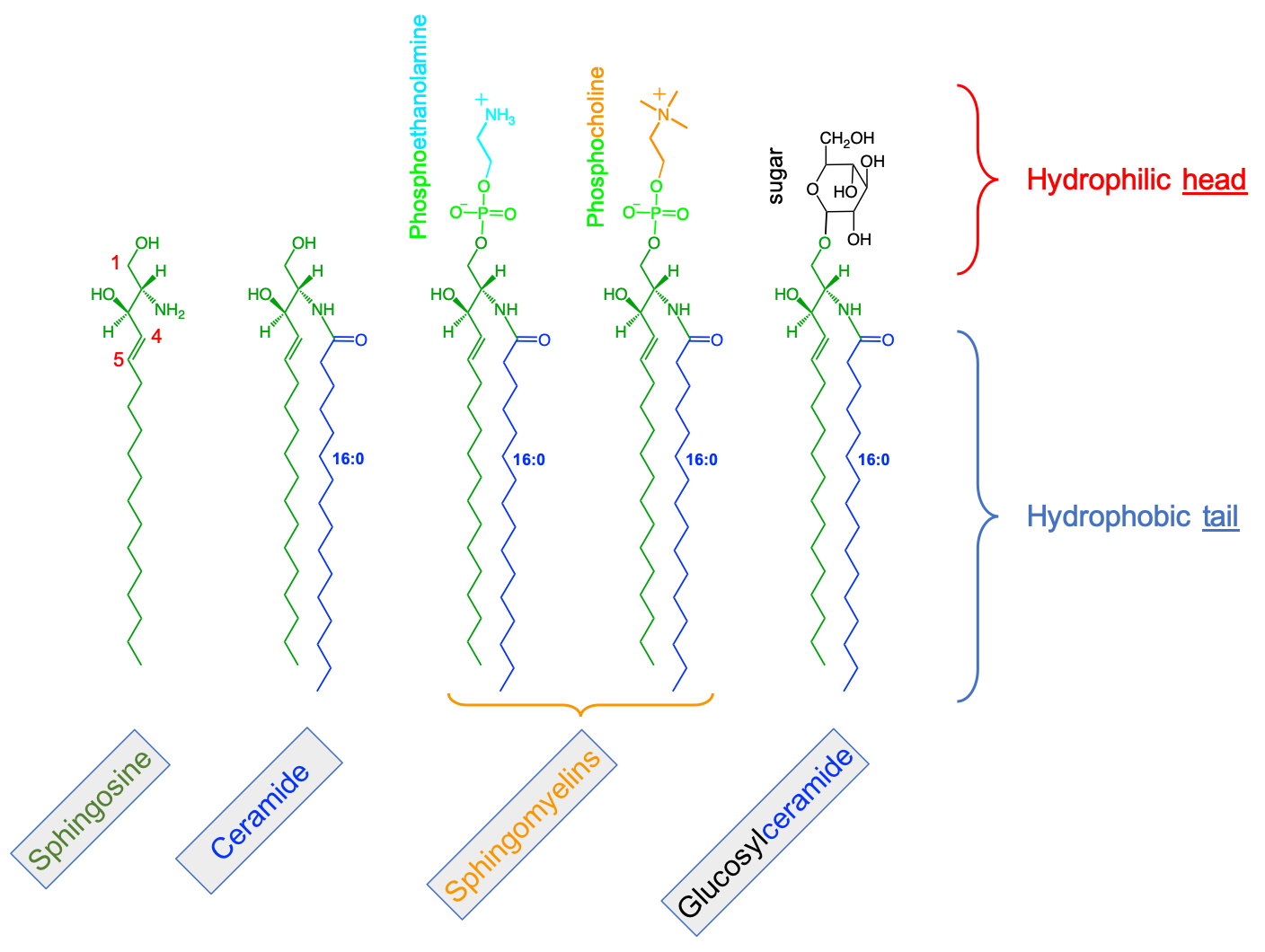

Figure 4.43: The main types of fatty acid based lipids: illustrating the common fatty acid base, and resulting from the three types of backbones and a variety of polar groups making the hydrophilic head)

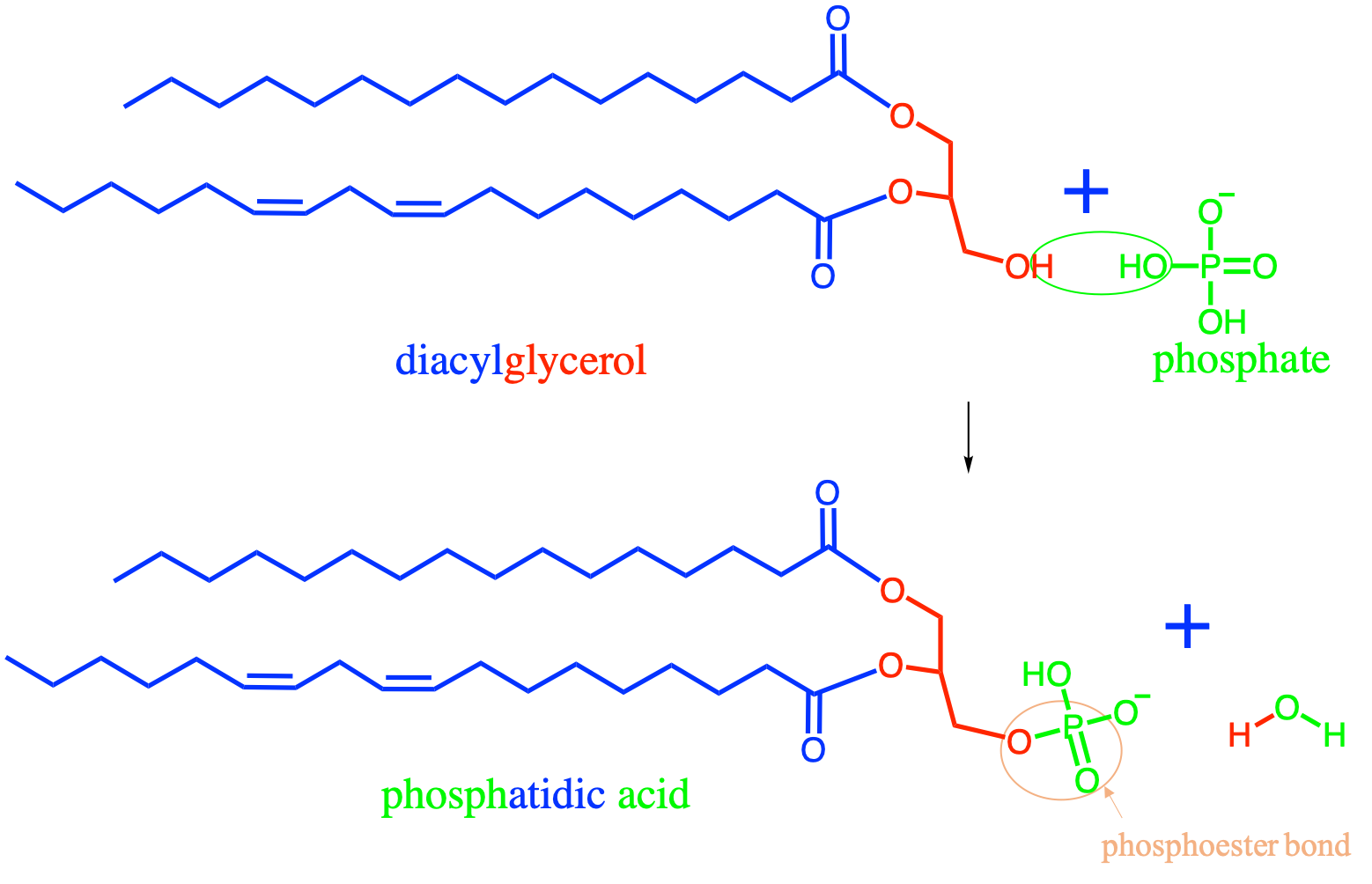

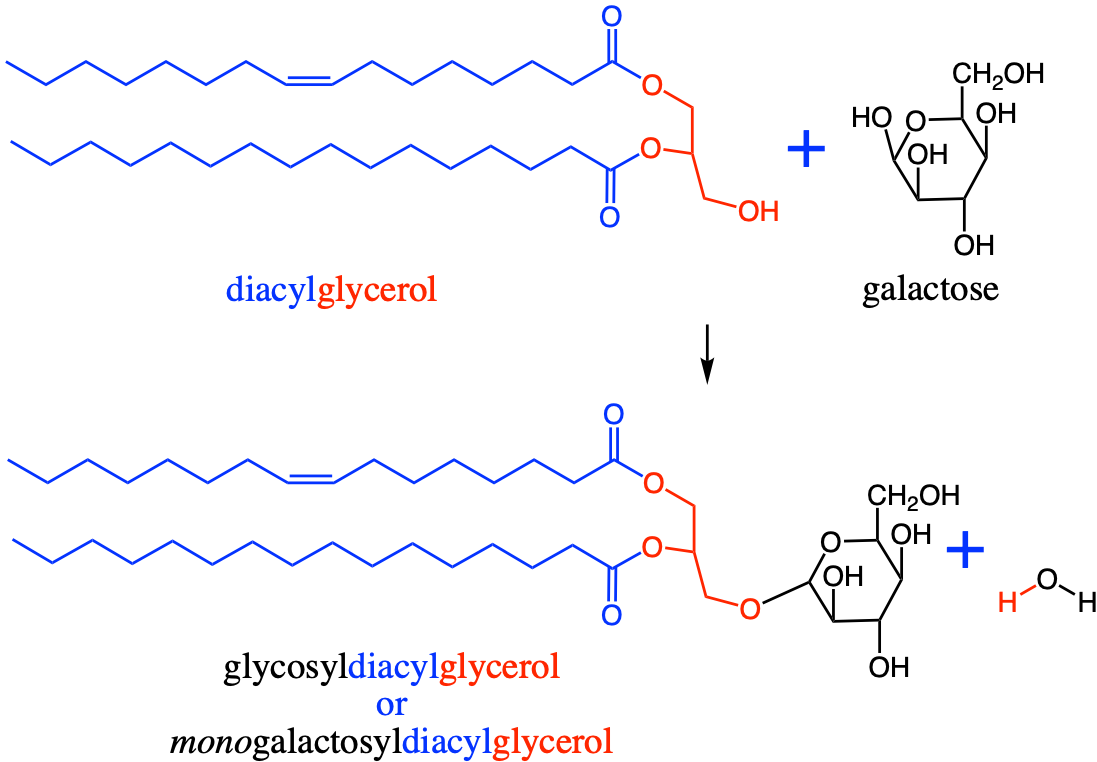

The second stage molecules are lipids built from fatty acids + a backbone. The backbone molecules can bind with one to three fatty acids on one side, with ester (most often), ether, or amide bonds, and with other radicals on the other side allowing more building blocks to be added. There are three main backbone molecules: glycerol, hexosamine (glucosamine in Figure 4.43), and sphingosine. Mono-, di- and triacylglycerols (previously called mono-, di-, and triglycerides, respectively) play such an important role in metabolism and energy storage, that the glycerolipids have been identified as a group of its own. Glycerolipids with additional building blocks eventually lead to the glycerophospholipid family (green in Figure 4.43). The glucosamine (hexose with an amine group) eventually leads to the saccharolipid family (blue in Figure 4.43). Sphingosine plays both the role of a backbone and of a fatty acid thanks to its long saturated aliphatic tail. Sphingosine-based lipids eventually lead to the sphingolipid family (grey in Figure 4.43).

The third stage are lipid molecules built from fatty acids + a backbone + phosphate or a sugar. It is quite interesting to realize that only two molecules, phosphate or an hexose, play that role. They have enough hydroxy functional group to make ester bonds with other groups. Most glycerophospholipids have a fourth stage of building blocks, and the third stage is thus an intermediate form. Many glycolipids and sphingolipids, however, only have stage three molecules and are incorporated into cell membranes as such.

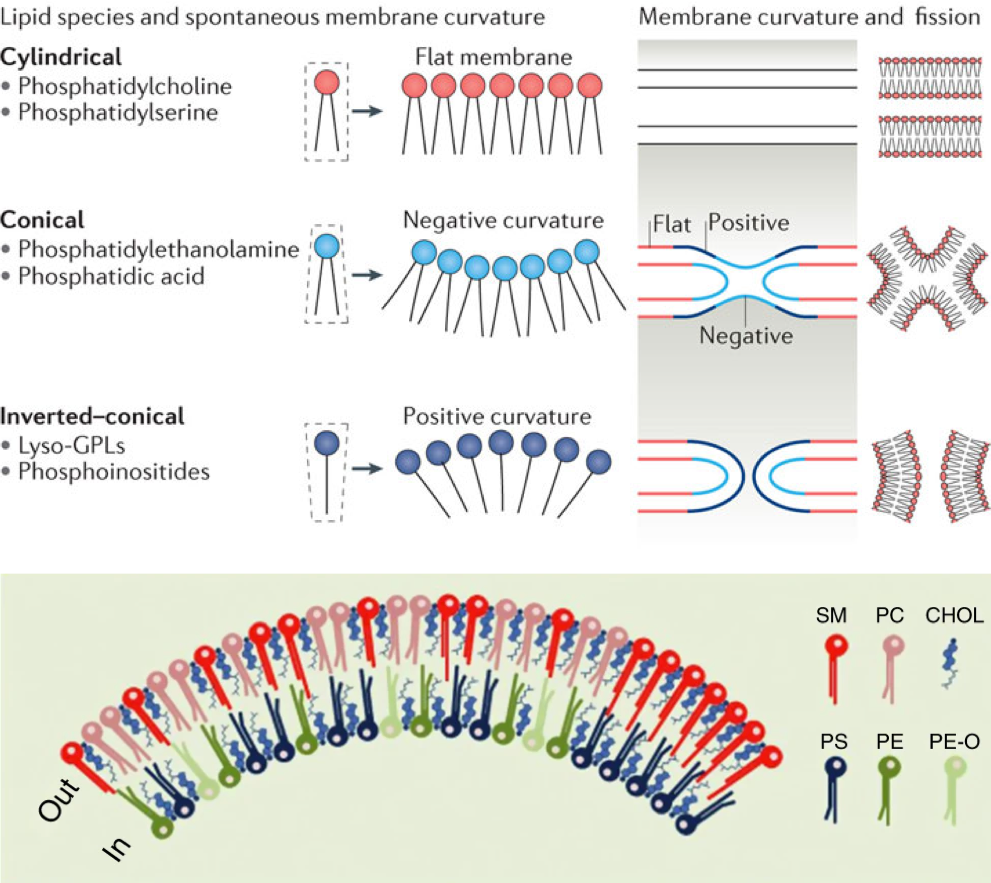

The fourth stage are lipid molecules with four building blocks: fatty acids + a backbone + phosphate or a sugar + polar group. These molecules make about 50% of the cell membranes and thus play a major role in life. It is the amphipathic nature of these molecules that leads them to readily assemble into acyl lipid bilayers (generally referred to as phospholipids). The hydrophobic tails and hydrophilic heads tend to aggregate together forming a layer or sheet of molecules a bit like a bundle of wheat that would have the stems together and the wheat ears together. Because cells essentially are aqueous systems, the hydrophobic side of the layer is naturally unstable, unless it is stabilized by another layer of phospholipids, with the hydrophobic tails facing each other and the hydrophilic heads facing the aqueous phase of the cell (more details later).

Third and fourth stage acyl-based lipids all have similar features: they have a hydrophobic tail group, and a hydrophyllic head group. As a result, they tend to naturally congregate together to form the famous lipid bilayer in which proteins and glycoproteins, serving as cell receptors, catalyzers, or exchange regulators can readily embed.

In summary:

- Lipids, unlike other molecular families, are not polymers of monomers but are built from building blocks

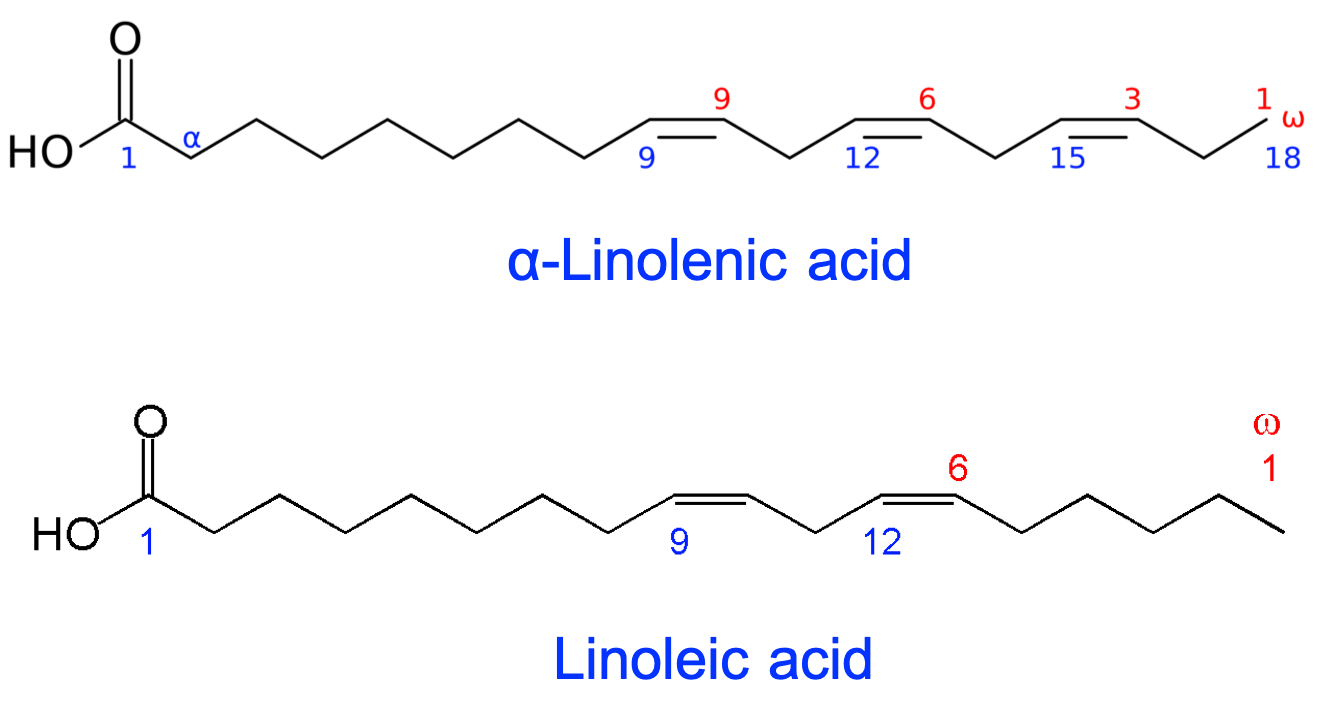

- Fatty acid long (C16-C22) saturated or unsaturated chains are the basis of what lipids are, sterols being an exception

- Because there are very few oxygen atoms, carbon atoms have more electrons for themselves and lipids thus serve as energy storage for the cell and organisms

- Most membrane lipids are made of two fatty acids forming a hydrophobic tail, linked to a hydrophilic head, thanks to a backbone intermediate molecule

- It is the amphipathic nature of lipids that allow the formation of a bilayer membrane which create cell compartments and in which proteins can be inserted

Time to pause in the strict biochemical description of acyl-based lipids, and spend some time to introduce an overview of the function of these lipids in cell membranes. This should make the description of these be more fascinating later on.

4.5.2 Lipids as key to cell membrane structure and function

In this section, lots of concepts are thrown at the reader, whom might be a bit rebuted by so many apparently complicated names (although most of them already appear in Figure 4.43). I decided to present the membrane function first in hope of making the biochemical description of enough of the lipids more interesting. So no worries, read this as a fascinating introduction to the wonders of life, and of lipids!

The first important concept to grasp is that in the lipid bilayer, the adjacent lipid molecules are not bonded together. It is thanks to their hydrophilic and hydrophobic interactions, and to a lesser degree thanks to electrostatic interactions, that the membrane lipids stay together and that cellular membranes exist altogether. The membrane does not have a solid crystalline nature, but rather a more fluidic nature, where molecules can freely move about within their layer or sheet. Proteins can insert themselves into this bilayer system thanks to the fluidic behavior. They too must have some amphipathic properties as well with hydrophobic and hydrophilic ends. Because proteins are inserted in a mosaic pattern, the fluidic mosaic model proposed in 1972 [Singer and Nicolson (1972); Figure 4.44] was the first accepted model to describe membrane bilayer.

![The **fluidic mosaic model** as published by Singer and Nicholson [-@Singer1972-ng]. The filled circles represent the ionic and polar head groups of the phospholipid molecules, which make contact with water; the wavy lines represent the fatty acid chains which make contact which each other. The membrane is made of **two layers or leaflet of lipids** mirroring each other and touching each other from the fatty acid side. The integral proteins are shown as globular molecules partially embedded in, and partially protruding from, the membrane](pictures/fluidic-mosaic-bilayer-1972.png)

Figure 4.44: The fluidic mosaic model as published by Singer and Nicholson (1972). The filled circles represent the ionic and polar head groups of the phospholipid molecules, which make contact with water; the wavy lines represent the fatty acid chains which make contact which each other. The membrane is made of two layers or leaflet of lipids mirroring each other and touching each other from the fatty acid side. The integral proteins are shown as globular molecules partially embedded in, and partially protruding from, the membrane

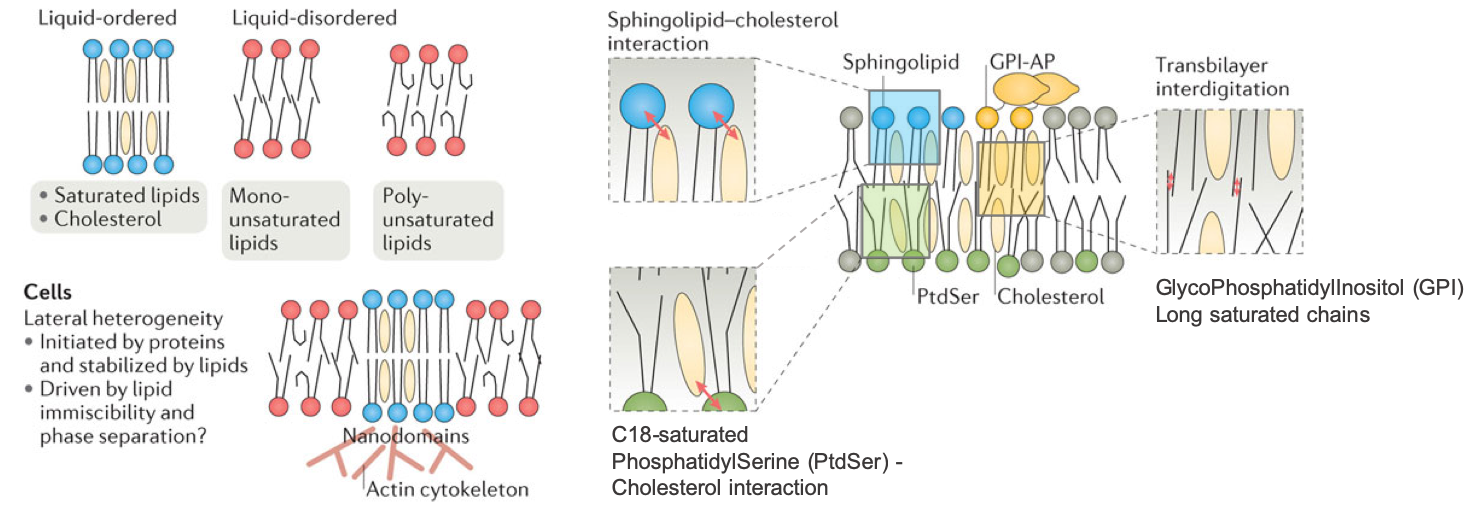

The second important concept is that the diversity of membrane lipids and their layout and interactions together allow the concurrent formation of fluidic and more rigid areas in the membrane itself corresponding to different phases. The two main phases are the liquid-disordered phase, very fluidic, almost liquid-like, and the liquid-ordered phase, more gel-like and more rigid.

The liquid disordered phase is a highly fluid state in which individual lipids can move laterally across the surface of the membrane relatively unhindered. Liquid-disordered bilayers are often characterized by irregular packing of individual lipid molecules, as well as the presence of kinks in unsaturated fatty acids. These kinks effectively reduce the surface area accessible to other fatty acid chains, weakening van der Waals interactions (Membrane Phase Transitions, libretext).

When the fatty acid chains are more fully extended because they are more saturated, and/or because they interact with sterols (details below), they become more fully packed and the van der Waals interactions are increased. They yields to a more rigid gel-like structure referred to as the liquid ordered phase. And guess what, this is where the proteins are also located and this makes sense because they have a more rigid structure in which to stay (Figure 4.45).

](pictures/lipid-raft-combined.png)

Figure 4.45: Membranes show a lipidic bilayer structure with lateral heterogeneity. Some lipids associate to form more dense areas known as membrane nanodomains or lipid rafts. In these domains, some proteins are included more frequently by electrochemical affinity. Cholesterol is located among the fatty acid chains, close to hydrophilic heads of the lipids, straighten fatty acids, and provide more rigidity to the membrane. Transmembrane proteins allow communication between extracellular and intracellular environments. Carbohydrates are found in the outer monolayer of the cell membrane forming the so-called glycocalyx. In this figure, the interactions of cell membrane molecules with cytoskeleton and with extracellular matrix are not depicted [Figure and caption after Pacheco Megías, Molist García, and Pombal Diego (2013) and Artur Jan Fijałkowski

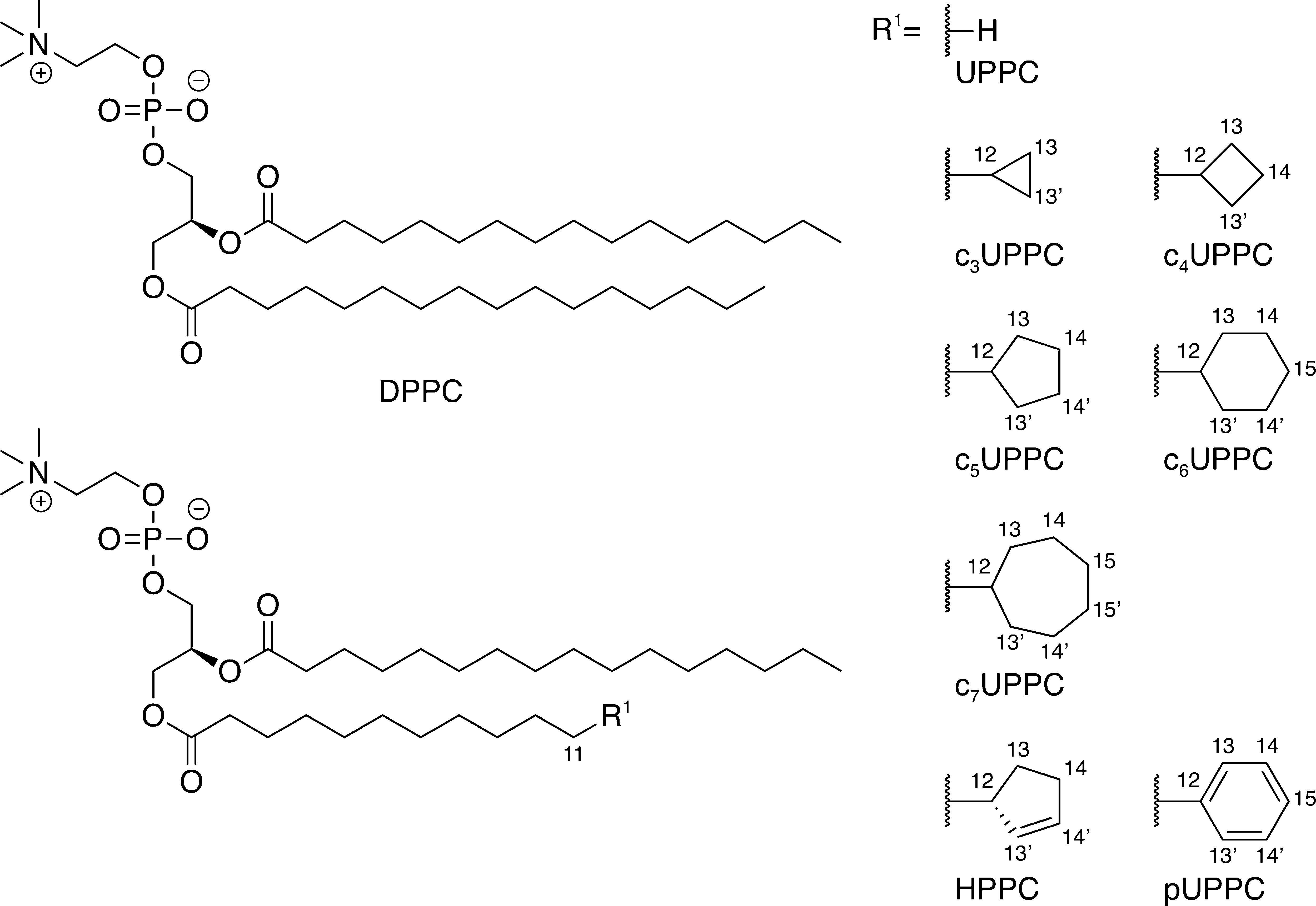

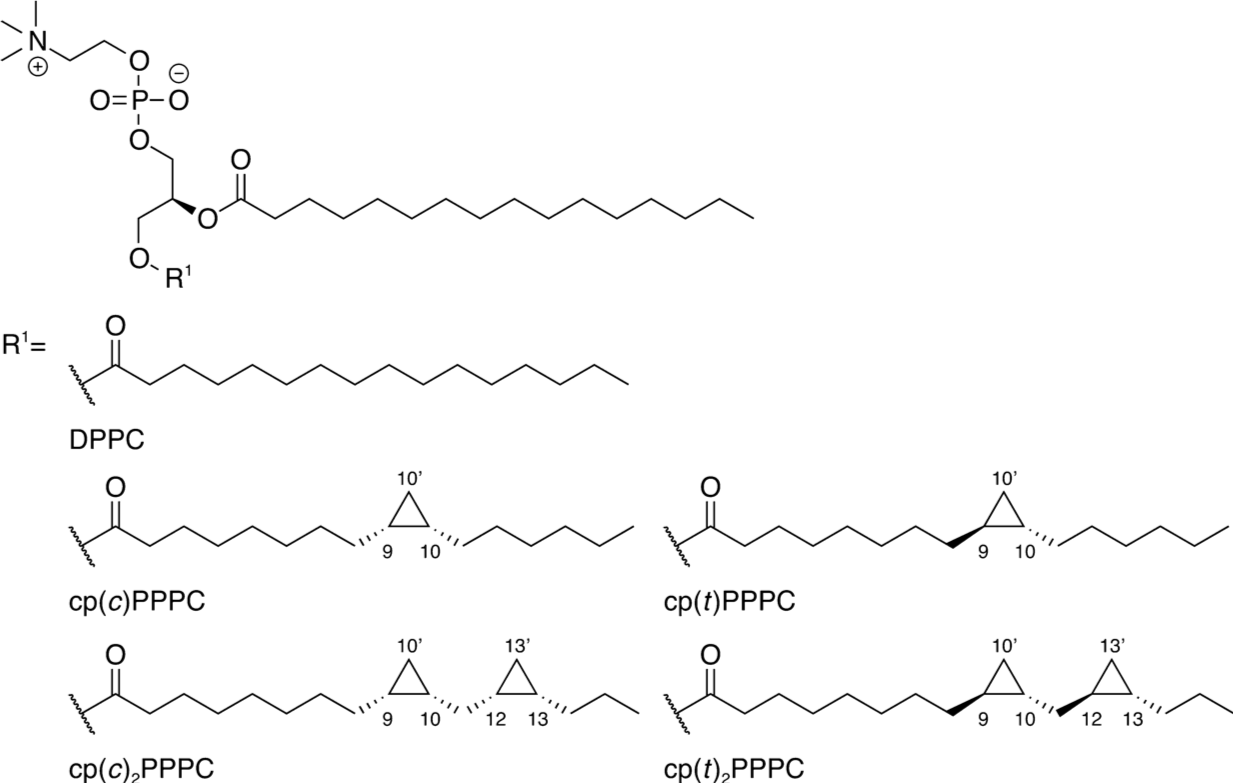

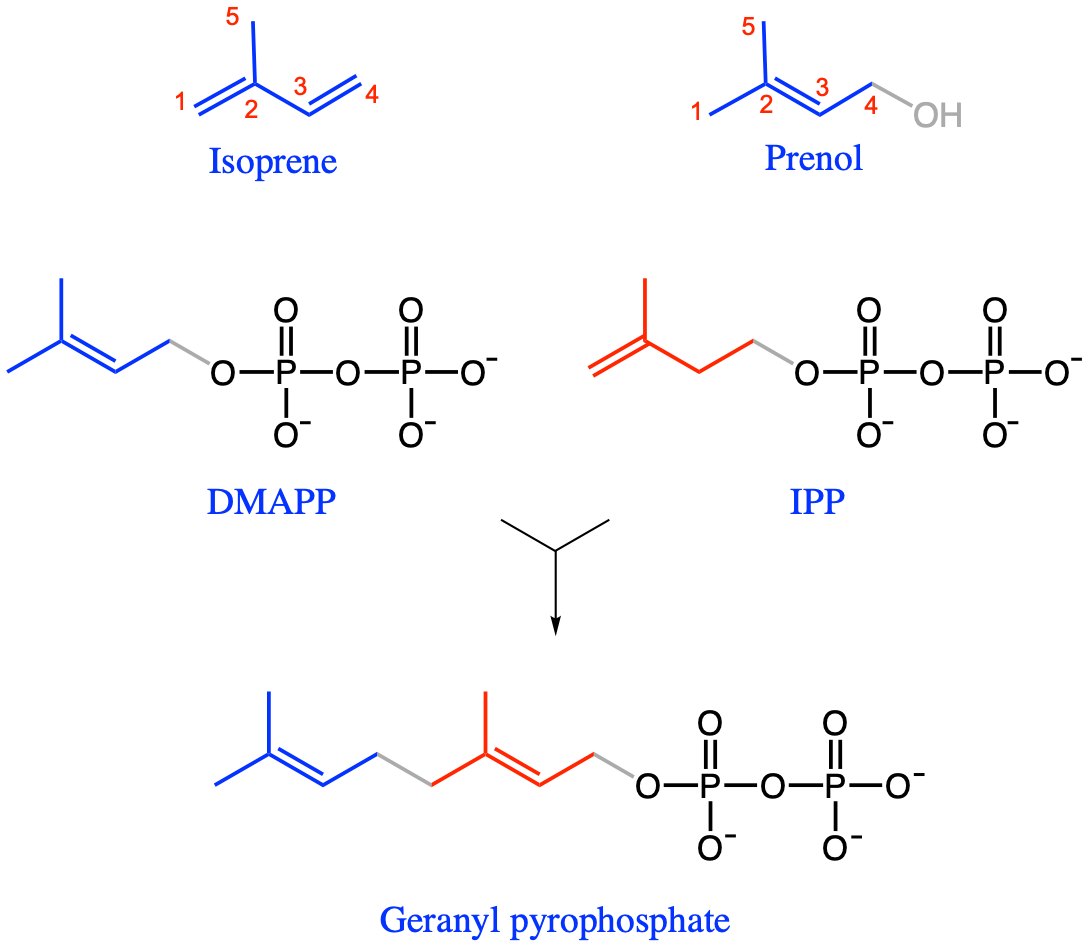

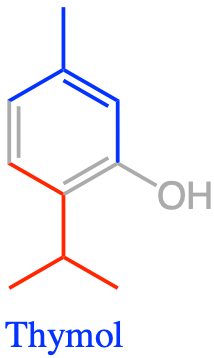

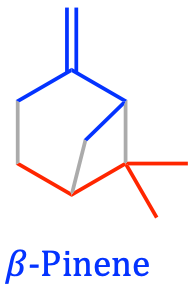

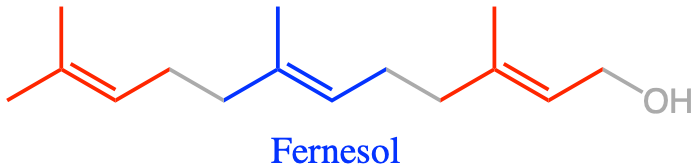

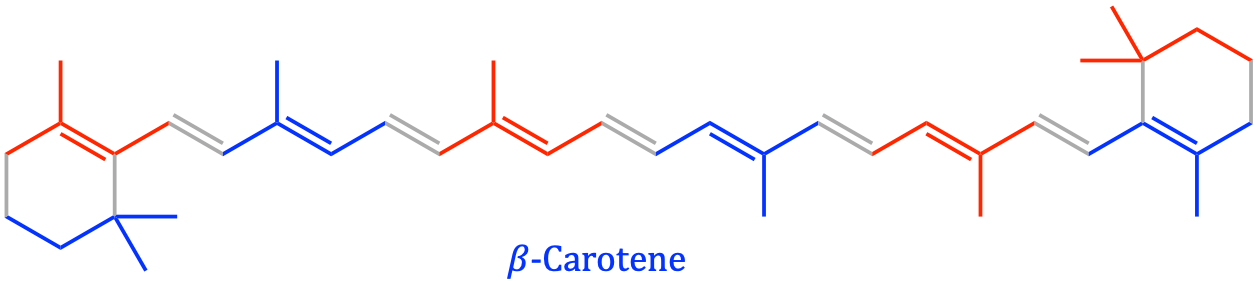

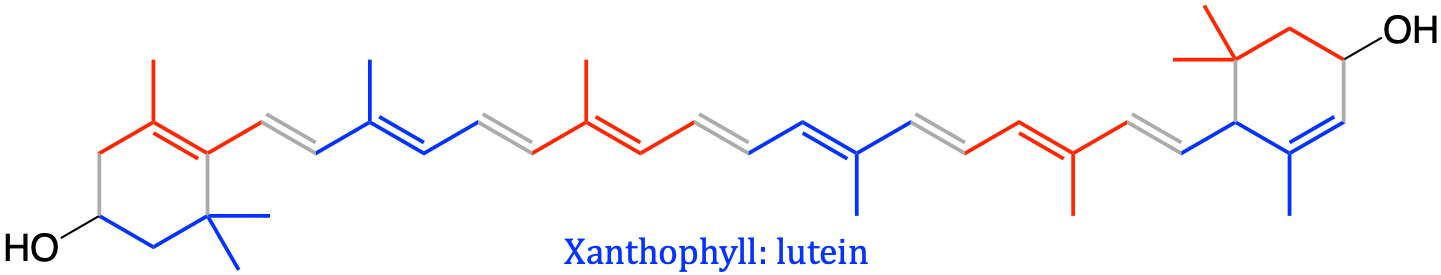

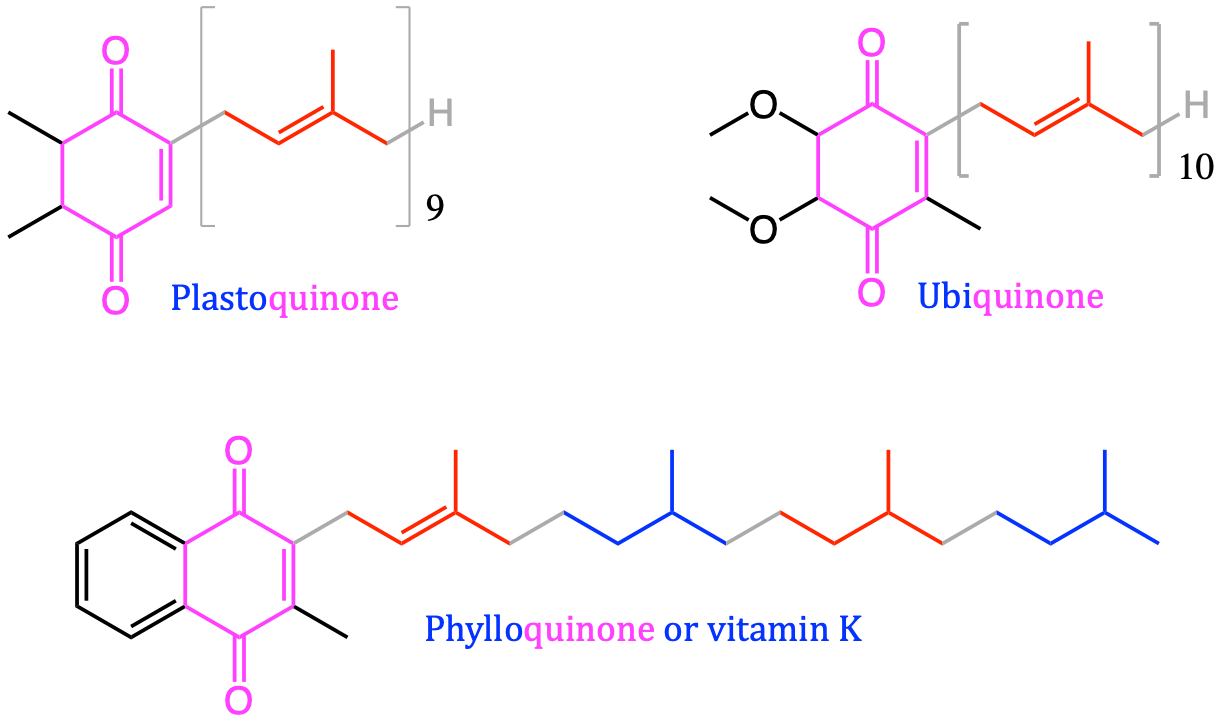

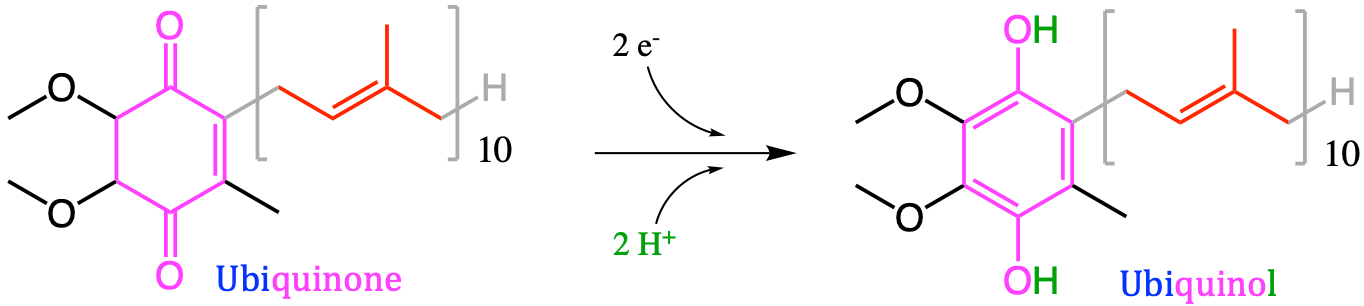

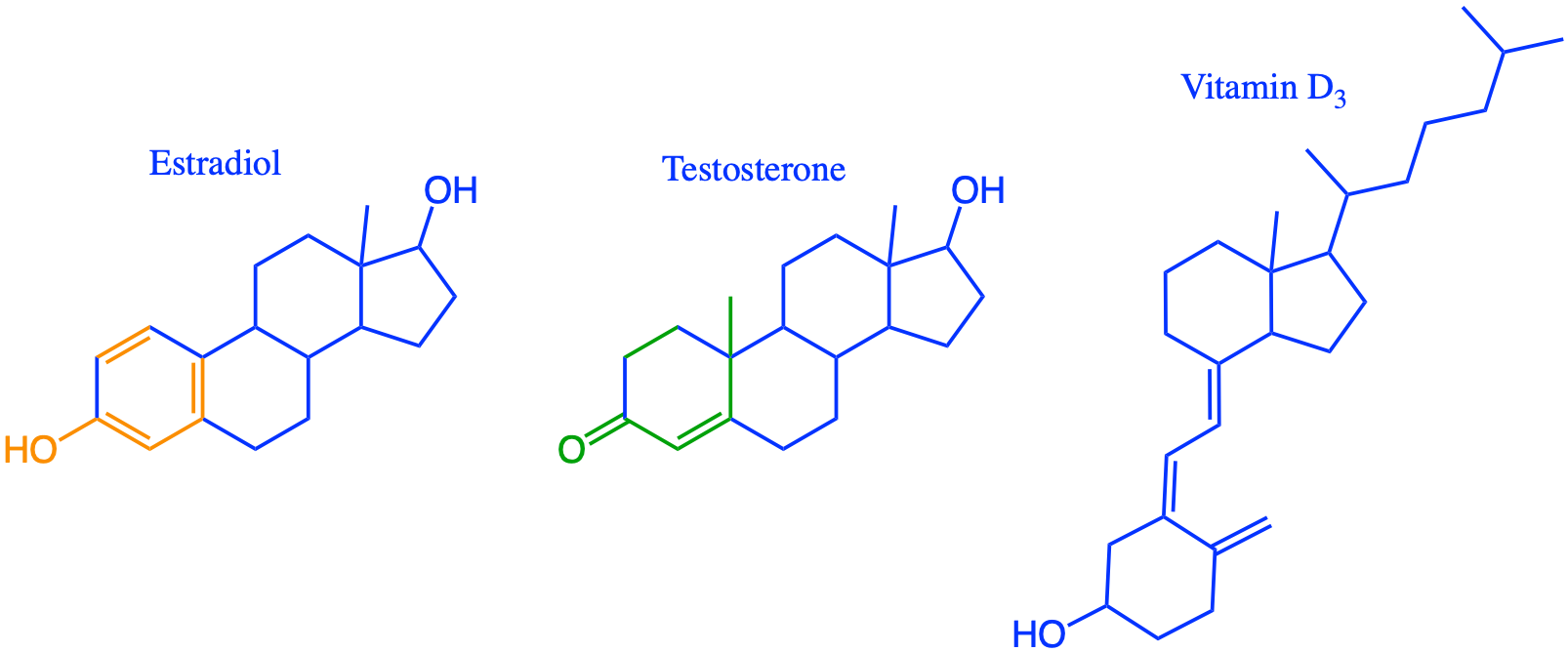

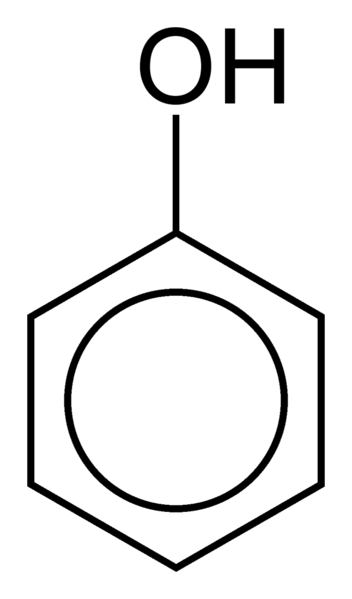

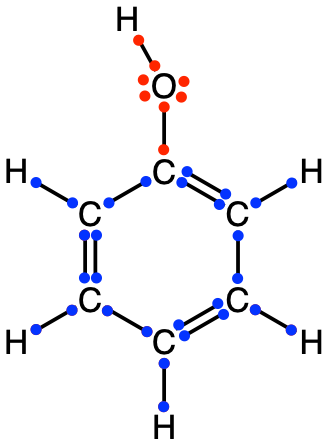

In other words, the number of unsaturated bonds in the fatty acid chains have a major impact on how fluidic the membrane is. The more unsaturated, the more kinks, and the more fluidic the membrane. Reversely, the more saturated, the less kinks, the more packed the hydrophobic tails, and the less fluidic the membrane. The addition of sterol lipids tends to generate the more rigid liquid ordered phase (Figure 4.46), and these tend to be present where the proteins are embedded in the membrane (Figure 4.45 and 4.47).