Chapter 8 The classical collection of electron donors and acceptors

Chapter summary:

- Most organisms on earth use organic matter as their electron donor and \(O_2\) as their electron acceptor

- Microorganisms have the ability to be facultative aerobs and can switch to anaerobic respiration

- Wetland soils host a series of very important electron donors and acceptors

- The consequences of respiratory processes are concentration gradients and movement of important ions and gases for ecological engineering

- Beyond wetlands, there are other respiratory processes relevant to biogeochemical processes in watersheds

In the previous chapters, we introduced quite a few details on the molecular functioning of respiratory and photosynthetic processes. We took aerobic respiration as our model to determine that most of the ATP produced in the cell is principally due to a proton flow from the inter-membrane space to the cytoplasm, for microbial cells and within the mitochondria for eukaryotic cells (Figure 5.29). In the middle of Chapter 5, we introduced respiration schemes as a very handy method to summarize the important drivers and consequences of respiration: the electron donors, the electron acceptors, and the byproducts of both oxidation and reduction. In this chapter we are going to explore the diversity of electron donors and acceptors present in nature, many of which represent important processes for ecological engineering. As a first step, we will use a theoretical wetland soil to explore some of the variety of respiration schemes. We will take advantage of these processes at play in wetland soils to explore the consequences on concentration gradients and movement of molecules of importance in environmental and ecological engineering. We will then introduce additional ways microbes have found to obtain their energy, and summarize the whole using the different prefixes for the word ‘trophs’.

8.1 The theoretical vertical sequence of respiratory processes in wetland soils

For this we will use a theoretical wetland soil to illustrate our point. Such theoretical soil has ‘enough’ organic matter content for microbial respiration to take place throughout its profile, ‘enough’ of other sand, silt, and clay and all the minerals that accompany them, including iron and manganese oxides. Let us assume that this theoretical soil, is sufficiently moist and aerated for microbial aerobic respiration to take place throughout the soil profile. Let us then assume that this soil is suddenly flooded, and let us explore the consequences of this. Respiratory processes are going to occur on a temporal sequence, which in fact will be mirrored by a vertical sequence of processes in the wetland sediment.

8.2 An aerobic layer near the soil-water interface

8.2.1 Oxygen supply and demand at the sediment water interface

The content or concentration of chemicals in any open liquid and gaseous systems results from the balance between supplies and demands. For example, the 21% of \(O_2\) in the atmosphere is a dynamic equilibrium between all the supplies of dioxygen to the atmosphere (mostly through photosynthesis), and all the demands. The same applies to gases, ions, and others dissolved in water. Let us now list the demands and supply of dioxygen at the top of the sediment.

8.2.1.1 Organotrophic aerobic respiration as oxygen demand

At the top of the wetland sediment, one can imagine that there will be fresh organic matter containing reduced carbon atoms, which microbes could as a source of energy, i.e., electrons in their respiration chain, and potentially also as a source of nutrients. And indeed, this is exactly what happens. Organotrophic microbes generate ATP for their metabolic needs by releasing the energy originally stored on the carbon atoms of organic matter through the transfer of electrons to dioxygen, which serves as electron acceptor. This demand for dioxygen can be further summarized as organotrophic aerobic respiration.

The suffix troph means feed on. In reality this suffix is rather vague and has been applied to qualify for organisms their source of carbon, electrons, and energy (details in section 17.16.1). Here, the word organotrophic means that the source of electrons, also referred to as reducing power, are the carbon atoms of organic matter. This is to differentiate from other sources of electrons that are not organic (in this case, lithotrophic as described below). Aerobic means that the electron acceptor is dioxygen, as opposed to the cases when dioxygen is not the electron acceptor, in which case the word anaerobic would be used. Respiration means that the transfer of electrons is a microbially mediated process corresponding to the production of ATP, as opposed to the cases where transfer of electrons is purely chemical and does not involve microbes.

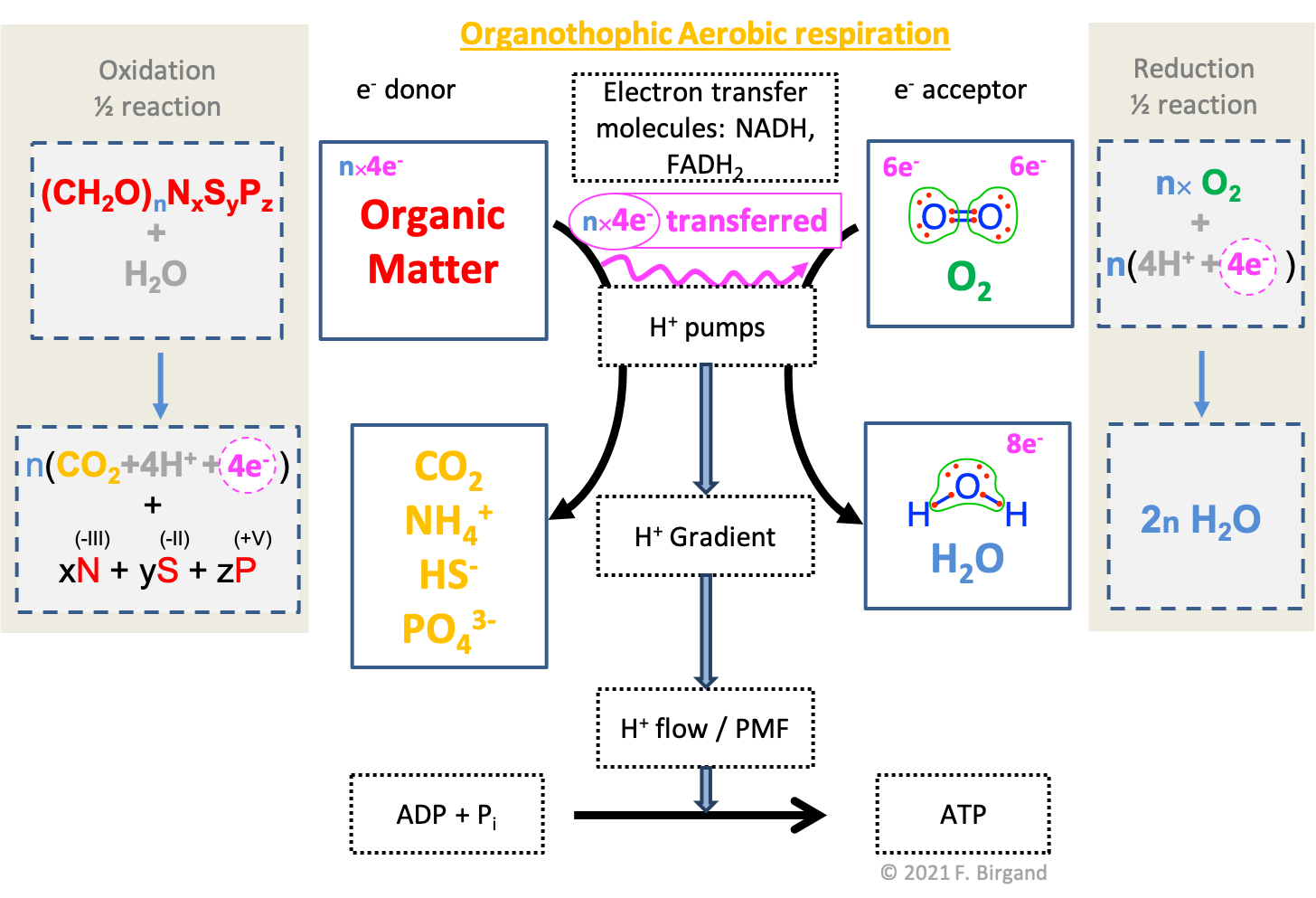

We have already presented in details the important steps at the molecular and membrane level of organotrophic aerobic respiration in Chapter 5 and summarized it in section 5.5.1). In Figure 8.1, we provide another view of organotrophic aerobic respiration using the electron transfer respiration scheme, to which the redox half-reactions have been added. We know since Chapter 4 that organic matter is, in its vast majority, composed of the \(CHONSP\) atoms, principally assembled into carbohydrates, proteins, lipids, nucleic acids, and phenolics.

We chose to summarize the formula of a generic organic matter as \((CH_2O)_nN_xS_yP_z\) to highlight the fate of each of the atoms. In the respiration processes, the entry molecule to the citric acid cycle is the acetyl radical \(-CO-CH_3\), on which 8 electrons are available on each carbon, for an average of 4 electrons per carbon atom (see Figure ??). This fittingly corresponds to the generic carbohydrate we introduced in section 5.5.1 and summarized as \(CH_2O\). As a result, it is fair to assume that for each carbon atom present in organic matter to be used as a fuel for respiration, 4 electrons are available, and for \(n\) carbon atoms, \(4n\) electrons are available, hence the use of \((CH_2O)_n\). We also know that the nitrogen and the sulfur atoms are assembled into amine and thiol groups, i.e., the atoms are fully oxidized and have 8 electrons for themselves. Phosphorus stays as fully oxidized in the form of phosphate \(PO_4^{3-}\) or phosphoryl \(-PO_3^{2-}\) groups and is incorporated as such in organic matter.

Figure 8.1: Combined electron transfer scheme with the electron allocation on the carbon of organic matter, the transfer of electrons, and the corresponding half redox reactions. Generic organic matter is summarized as \((CH_2O)_nN_xS_yP_z\). During organotrophic aerobic respiration, carbon is fully oxidized into \(CO_2\), while the atoms of \(N\), \(S\), and \(P\), stay in the oxidation state when assembled in organic matter. The oxidation states for \(NSP\) as byproducts of respiration respectively are -III, -II, and +V, corresponding to \(N\) and \(S\) having 8 electrons for themselves, and \(P\) having none

The additional information provided in figure 8.1 are the redox half-reactions, compared to Figure 5.21. We added these to further illustrate that in organotrophic aerobic respiration, only the carbon atoms get oxidized. the other atoms keep their oxidation state, in other words their electrons if they have any, as they did when assembled

transferring electrons originally and the consumption of oxygen by microbes corresponds to what w At first, all micro-organisms are going to use dioxygen that might be present in the pore space. But because pore space is now getting filled with water, it is possible that the amount of oxygen available for microorganisms might change. And yes, indeed, water does not have nearly the capacity to provide oxygen as air does for several reasons:

- at 15°C in water there are about 10 mg of \(O_2\) in one liter of water. Comparatively, in one liter of air, there is about 300 mg of \(O_2\), or 30 times more. How does one calculate this? At standard conditions, 1 liter of air at 21% oxygen possesses 0.21 L of oxygen. Since for these conditions, 1 mole of gas occupies 22.4 L, simply divide 0.21/22.4, to arrive at 0.0094 moles of oxygen. Then the mass of oxygen in 1 liter of air is 0.0094×32 g/mole = 300 mg. A lot more details are available in Chapter 13 on dissolution of gases in water.

- the diffusivity (which quantifies the ability of elements to move about) of \(O_2\) in air is 0.176 cm²/s while that of \(O_2\) in water is 2.10×10−5 cm²/s, or more than 8,000 times smaller (Wikipedia contributors 2017)

In other words, it is good to remember that the amount of oxygen available in water compared to air is about 30 less, and that oxygen in water moves more than 8,000 slower in water than in air.

So, one can clearly see that the potential supply of oxygen from flooded porewater is thus a lot more limited than in aerated pore space. Now, where is the potential source for supply of oxygen for our recently flooded soil? The answer is:

- reaeration from the air at the water-atmosphere interface

- photosynthesis from algae and aquatic vegetation during the day

In all cases, most of the oxygen needed for microbial aerobic respiration of our new flooded soil will have to travel the distance corresponding to the thickness of the water column, and, the linear distance within the porous medium of the soil, which can be quite tortuous. This property of the soil/sediment has been factored in by researchers and been called tortuosity.

In summary, the supply of oxygen to bacteria in a flooded soil is limited because of four factors:

- there is about 30 times less \(O_2\) in water than there is in the same volume of air

- the \(O_2\) diffusive transport capacity in water is about 8,000 times smaller than that in air

- \(O_2\) has to travel from the atmosphere to the soil through the thickness of the water column, and

- travel through the tortuous path of the soil porous medium

In addition to these four rules, which apply to all aquatic systems, the velocity of water matters very much in the reaeration process, which corresponds to factor 1 above: reaeration is much higher for streams than for stagnant waters (see Chapter 11). In other words, the stagnant water above our flooded wetland soil example, is another factor, compared to streams, which further limits the supply of oxygen to the aerobic bacteria in the flooded soil. This is developed at length in Chapter 13 of this book.

Not surprisingly, this supply is just too limited compared to the demand. As a result, most of our recently flooded soil bacteria consumes all the \(O_2\) and the only part of the sediment that might have a little bit of oxygen is the area at the soil-water interface. This is what is illustrated in Figure 8.2 below.

Figure 8.2: Animation summarizing the formation of aerobic and anaerobic layers of a theoretical flooded wetland soil due to the imbalance between bacterial respiratory oxygen demand and oxygen supply through the water column

Because of the \(O_2\) demand in the sediment, an \(O_2\) concentration gradient forms from the soil-water interface down. This concentration gradient, in turn, drives a downward movement of oxygen from the water column into the sediment. Because the \(O_2\) demand exceeds the \(O_2\) that can be supplied because of all the limitations described above, there is a depth at which all the oxygen has been consumed above. This depth defines the beginning of the anaerobic zone of the sediment, and above it, the aerobic layer of the sediment.

Now that we have explored what organic matter was in Chapter 4, it is important to recall that in all molecular families of the primary metabolites, and many of the secondary metabolites, the atoms of nitrogen and sulfur are assimilated always as fully reduced, that is that they have 8 electrons for themselves because they are bonded to carbon atoms.

To be perfectly correct, there are few exemptions when \(N\) and \(S\) atoms are involved in functional groups called nitro, and sulfo (not mentioned in Chapter 3 because they are rare and anecdotic in nature) where they are bonded to oxygen atoms, in which case they have lost most if not all their electrons to oxygen. Another exception that needs to be cited is the disulfur bridge functional group very common in proteins, where two thiol groups interact together to form a \(-S-S-\) bond. In that case, each sulfur only has 7 electrons for itself. However, the sulfur atoms regain their electrons upon the disulfur bridge breakup thanks to electron donors. In all cases, during respirations (aerobic and anaerobic) the sulfur atoms will always appear as in thiol groups and as a result always appear to carry 8 electrons for themselves. We saw in Chapter 4 that the nitrogen atoms appeared in organic molecules as primary, secondary, and tertiary amines (details in section 3.2.4), but that in all cases, the nitrogen had all 8 electrons for itself.

8.3 Respiration in the anaerobic zone of the soil

What happens to all the microbes in the anaerobic zone of the sediment? Certainly the exclusively aerobic microbes just do not survive, but most bacteria are facultative aerobs. In other words, they can switch from aerobic to anaerobic respiration. Let us state this again: in the anaerobic zone of the sediment, only unicellular microorganisms are able to survive and have had to adapt their respiration to still be able to produce ATP for their metabolism, but using electron acceptors other than \(O_2\).

It turns out that thermodynamics dictate that not all electron acceptors can generate the same amount of energy when they strip electrons from their electron donors. As a result, one can classify electron acceptors in decreasing order from the most to the least oxidizing, and the list of preferred electron acceptors goes as such:

- nitrate or \(NO_3^-\)

- Manganese oxide (\(MnO_2\)) or \(Mn \space (IV)\)

- Iron oxides/hydroxyde or \(Fe \space (III)\)

- sulfate or \(SO_4^{2-}\)

- Carbon dioxide or \(CO_2\)

Although very different microbes are involved at the different stages, the apparent demand for electron acceptor, in our theoretical wetland soil, can be described as a temporal sequence of events: oxygen is the preferred electron acceptor; when \(O_2\) is all used, \(NO_3^-\) will be used as the preferred electron acceptor; when all the \(NO_3^-\) is used, the next most powerful electron acceptor is \(MnO_2\) (also referred to \(Mn \space (IV)\); IV corresponds to its oxidation state), which is present in a solid or mineral form in soils; when all the \(MnO_2\) is used, then iron oxide or hydroxyde, which are also in the solid phase (also referred to \(Fe \space (III)\), III corresponds to its oxidation state) will be used as the preferred electron acceptor; when all the \(Fe\) is used, then \(SO_4^{2-}\) is used as the next preferred electron acceptor, and then when finally all the other electron acceptors have been all used, \(CO_2\) can be the ultimate electron acceptor…!

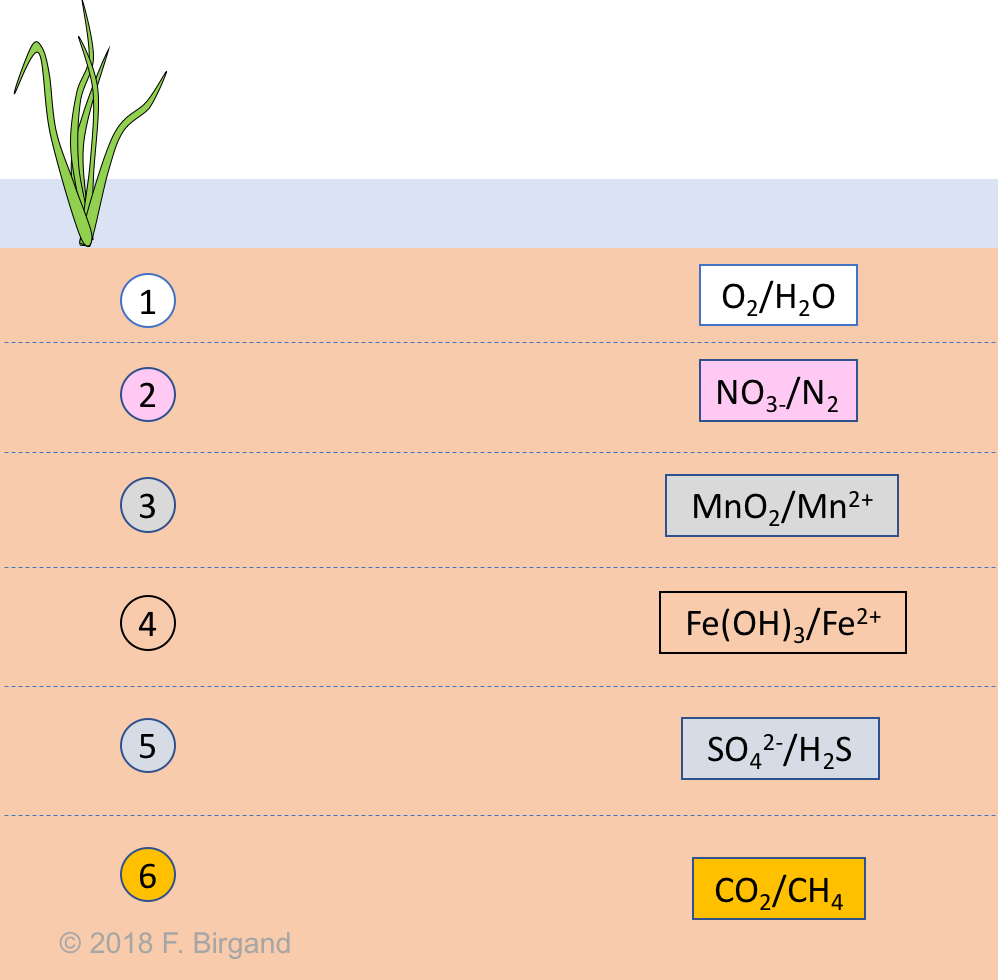

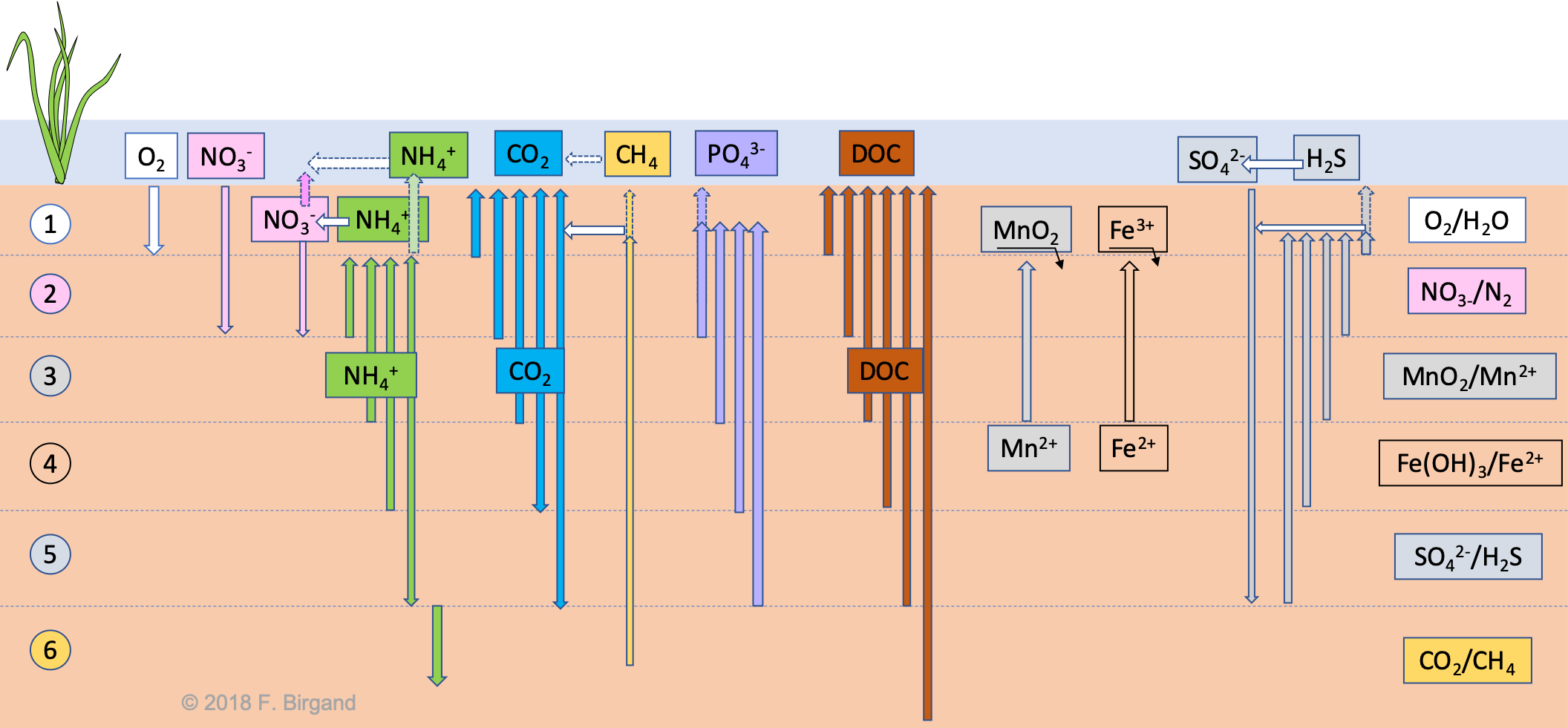

Finally, to this temporal sequence corresponds a theoretical spatial sequence or layers where each of the electron acceptor essentially defines a soil layer, with the layers organized with depth from the most to the least oxidizing electron acceptor as represented in Figure 8.3

Figure 8.3: Theoretical spatial layering of wetland soils corresponding to the electron acceptor available, not too long after flooding. In each layer, the oxidizing and the reduced forms are illustrated as oxidizing/reduced. Not to scale

It is now time to present the respiration processes in each of the redox layer.

8.4 A denitrification layer below the aerobic layer

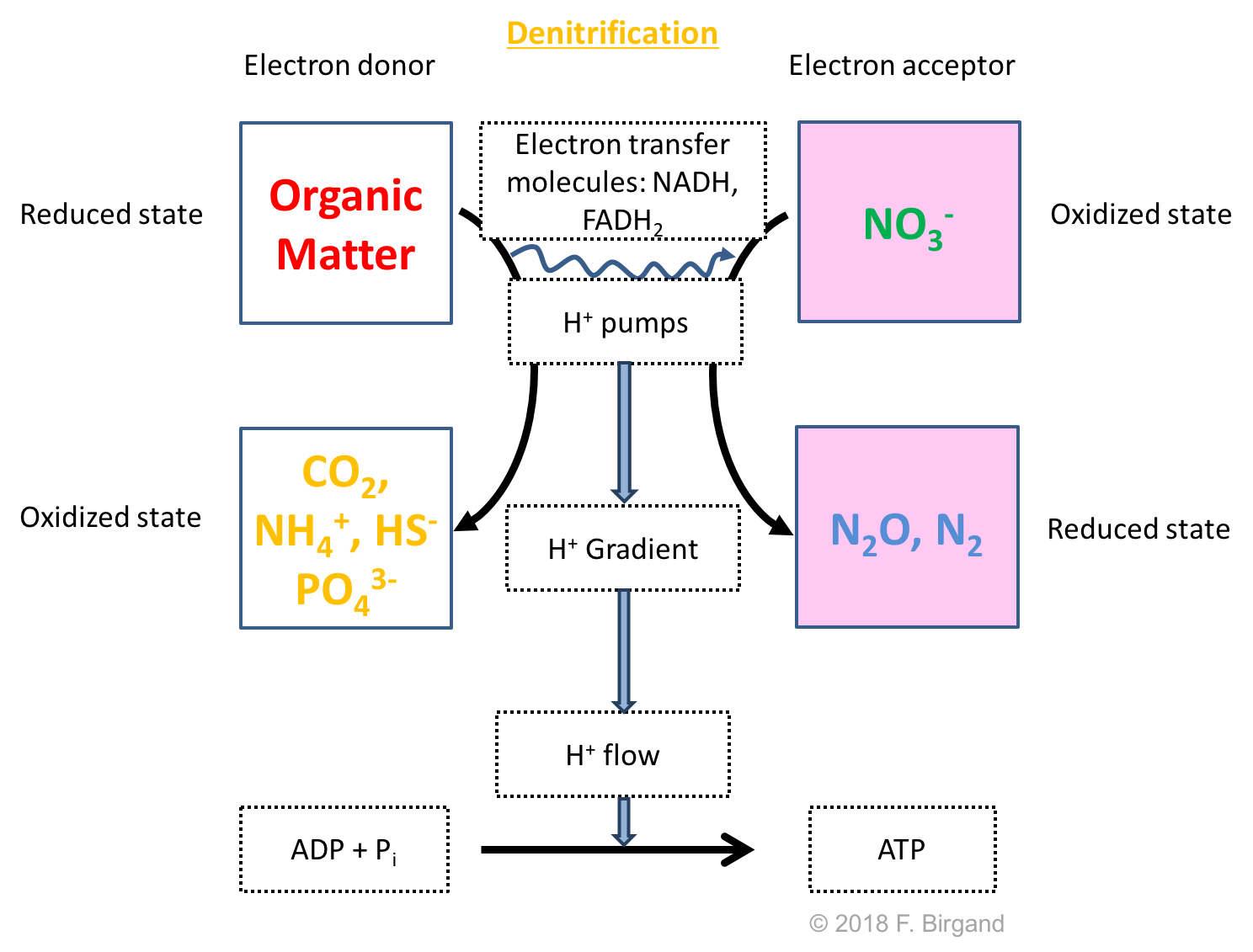

The next most powerful or oxidizing electron acceptor after \(O_2\) is \(NO_3^-\). We have seen in the previous chapters that the N atom in nitrate has zero electron for itself, hence its ability to accept electrons. Just like for aerobic respiration, nitrate reduction just does not happen on its own. Facultative anaerobic bacteria called denitrifiers take advantage of the electrons available on organic matter and of nitrate to accept them to generate their energy. The denitrification of this theoretical wetland soil is referred to as heterotrophic denitrification because the source of carbon for these denitrifiers is also the source of electron, as OM is the source of both. The autolithotrophic denitrifiers, which use pyrite FeS2 as their source of electrons, are presented later in this chapter.

There are two possible byproducts of nitrate reduction: N2, which is the inert gas that makes 78% of our atmosphere, and N2O, which is a potent greenhouse gas. The byproduct of the oxidation of OM are the same as the ones in aerobic heterotrophic respiration, i.e., \(CO_2\), NH4+, HS-, and PO43-.

Figure 8.4: Respiration scheme for heterotrophic denitrification

In reality, denitrification involves not a direct reduction of nitrate into N2 or N2O, but rather a sequence of reductions, summarized in equation (8.1), where nitrite, nitrogen monoxide, and nitrous oxides are intermediate products:

\[\begin{equation} NO_3^- \rightarrow NO_2^- \rightarrow NO \rightarrow N_2O \rightarrow N_2 \tag{8.1} \end{equation}\]

Nitrous oxide is thus evidence of an incomplete denitrification. Because denitrification currently is the one mechanism, which removes nitrogen from the aqueous phase as gaseous byproduct, it currently ranks as the most effective ways to treat excess nitrogen in water. Entire research programs are dedicated to the development of methods and treatment systems to optimize this process. One of the active research areas is about finding ways to have denitrification go all the way to the N2 stage to minimize the production of N2O.

Because this is a reduction process, and because nitrate is not assimilated in the denitrifier cells, a very short and good definition of denitrification is the microbially mediated dissimilatory reduction of nitrate into dinitrogen. The nitrogen atoms in the N2 molecule have 5 electrons for themselves. For complete denitrification, this means that the nitrogen atom has gained 5 electrons from \(NO_3^-\) to N~2. We will see in this chapter that it is possible to numerically show this in what is referred to as redox half reactions.

A more complete and more descriptive definition of denitrification is

Denitrification refers to the dissimilatory reduction, by essentially aerobic bacteria, of one or both of the ionic nitrogen oxides (nitrate, \(NO_3^-\), and nitrite, N\(O_2\)-) to the gaseous oxides (nitric oxide, NO, and nitrous oxide, N20), which may themselves be further reduced to dinitrogen (N2). The nitrogen oxides act as terminal electron acceptors in the absence of oxygen. The gaseous nitrogen species are major products of these reductive processes (Knowles 1982).

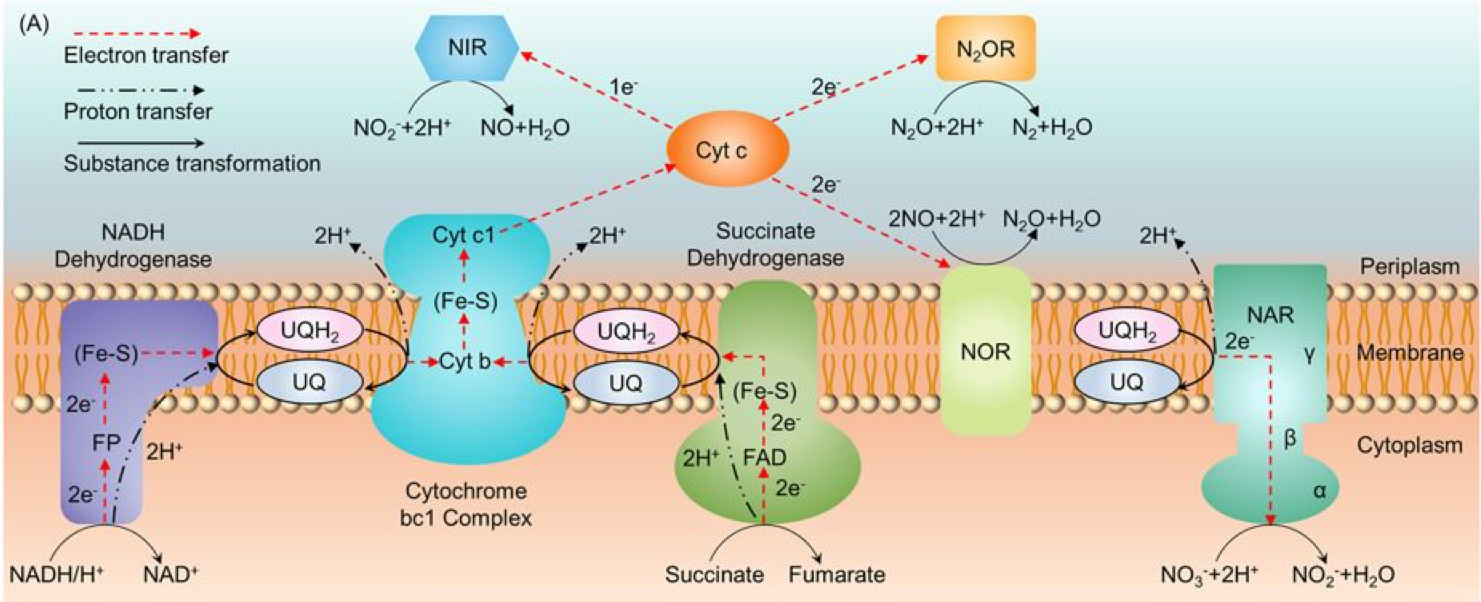

The details of the electron transfer near the denitrifiers inner membrane are actually different (Figure 8.5) than those of aerobic respiration as illustrated in Figure ?? in this chapter. More proteins are involved, which descriptions are provided in Figure 8.5. The details of the denitrification of the electron transfer chain are beyond the purpose of this book. However, it is important to recognize that the electrons, originally stored on organic molecules, are brought to the membrane on the cytoplasm side by the electron transfer molecule NADH, just as is the case for aerobic respiration. It is also important to see that protons are pumped from the cytoplasm to the periplasm by ‘proton pumps’ such as cytochromes, and nitrate reductase powered by ubiquinone. Although the ATPase is not illustrated in Figure 8.5, the proton gradient formed in the periplasm does generate the proton motive force for the synthesis of ATP. In the end the electron transfer scheme of denitrication illustrated in Figure 8.4 holds, and sufficies for our purpose.

Figure 8.5: Summary of Electron Transfer Chain for heterotrophic denitrification (after Su et al. (2015)). NAR: Nitrate reductase; NIR: nitrite reductase; NOR: nitric oxide reductace; N2OR: nitrous oxide reductase; UQ: ubiquinol; Fe-S: iron-sulfur protein; Cyt b, Cyt c: cytochrome b and c

Denitrification is thought to be inhibited by the presence of oxygen, and thus only occurs in our theoretical wetland soil, below the aerobic layer. However, denitrification only occurs if there is nitrate present as electron acceptor. Therefore, for denitrification to proceed, there must be a supply of nitrate that can compensate the demand due to denitrification. The only place from where nitrate can be supplied, is the water column, and, possibly, the aerobic layer of the sediment where nitrification can take place, as we shall see later.

Following the same analysis as that of aerobic respiration, the demand for nitrate creates a downward flux of nitrate from the water column down. Because of the transport distance for nitrate from the water column and through the aerobic layer of the sediment, the supply tends to be lower than the demand. This suggests that at one point in depth there will be no more nitrate as they are consumed faster than they can diffuse downward. Nitrates thus diffuse through layer 1, and both diffuse and are consumed as electron acceptors in layer 2 in Figure 8.3. Again, because the demand exceeds the supply, nitrates cannot move further down than the bottom of layer 2. Denitrification is thus theoretically restricted to layer 2.

8.5 Manganese and Iron oxides reductions

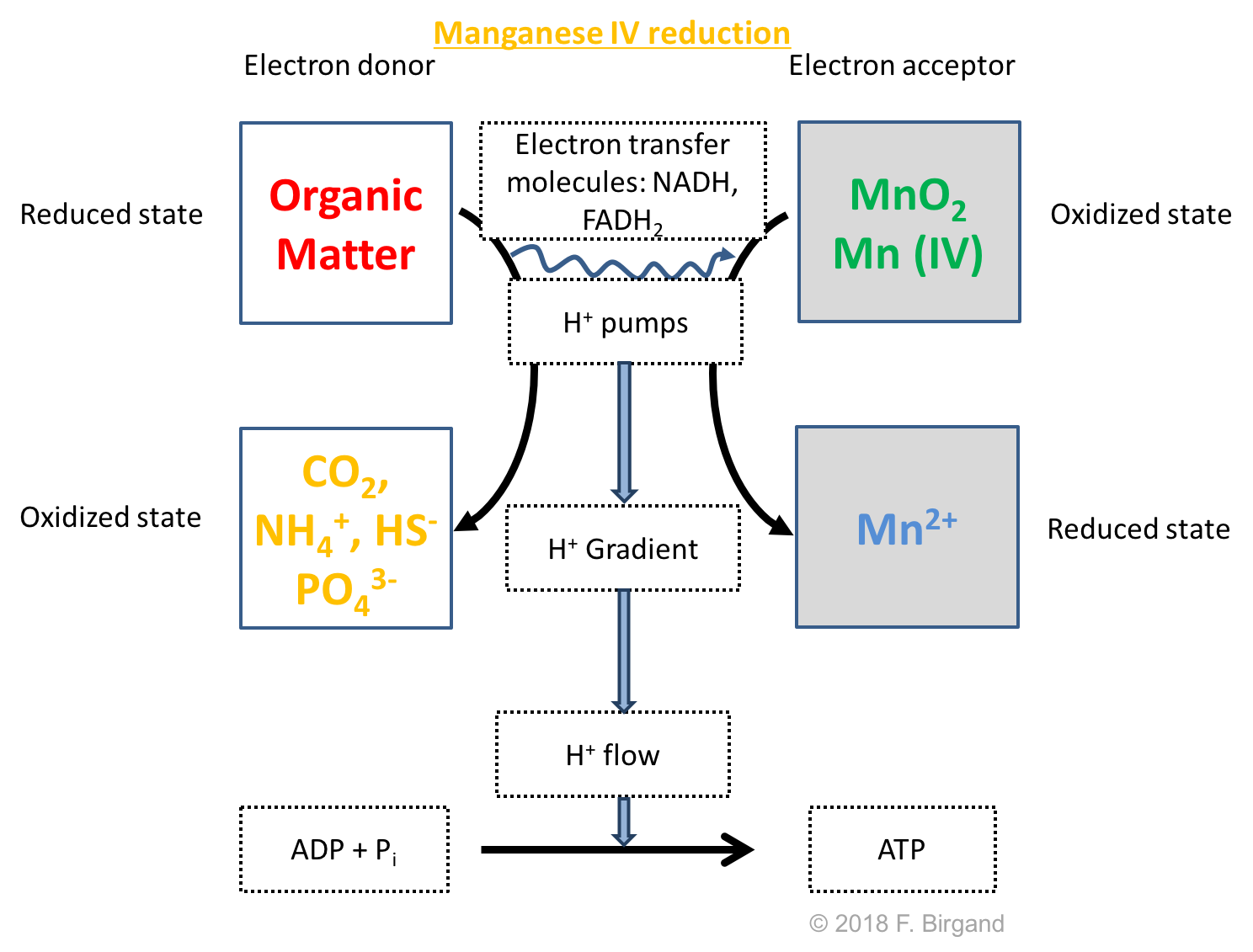

Below the denitrification layer, microbes have to find new electron acceptors for their respiration. After \(O_2\), which is a gas, \(NO_3^-\), which is a dissolved anion, the next elements which serve as electron acceptors are solids: Manganese and Iron oxides. They will serve as electron acceptors, only if soil minerals containing \(Mn\) and \(Fe\) oxides are present. In our theoretical wetland soil, the assumption is that these oxides are present. In layer 3 (Figure 8.3), \(MnO_2\) serve as the electron acceptor. In the \(MnO_2\) minerals, the manganese is in the \(Mn\) (IV) form, and can accept up to 2 e- to become the mobile \(Mn^{2+}\) cation. The quantitative details of the transfer of electrons are given in in this chapter. Overall the Manganese reduction respiration scheme is illustrated in Figure 8.6.

Figure 8.6: Respiration scheme for heterotrophic Manganese oxide reduction

While the electron acceptor is immobile, the reduction of \(MnO_2\) produces \(Mn^{2+}\) ions, which are dissolved, mobile in water, and can diffuse following concentration gradients. In our original hypothesis of the sudden flooding of the wetland soil, \(MnO_2\) oxides would be reduced from layer 3 down. The \(Mn^{2+}\) ions produced in these layers, and the lack of \(Mn^{2+}\) ions in layers 1 and 2, would create a concentration gradient, which would generate an upward flux of \(Mn^{2+}\), this time, from layers 3 to 6 into layers 2 and 1. The fate of \(Mn^{2+}\) ions as they reach the aerobic layer is discussed below.

The global significance of managenese reduction to carbon oxidation in aquatic sediments seems to be rather low (reviewed in Thamdrup 2000), and less than 10% of total benthic mineralization.

The contribution of organotrophic \(Mn\) reduction is limited by the low \(Mn\) content with depletion of \(Mn\) oxides within the upper 1-2 cm of most sediments and by slow reaction kenetics relative to the competing inorganic reduction. In contrast to Mn, \(Fe\) reduction contributes significantly to carbon oxidation in many sediments (Thamdrup 2000).

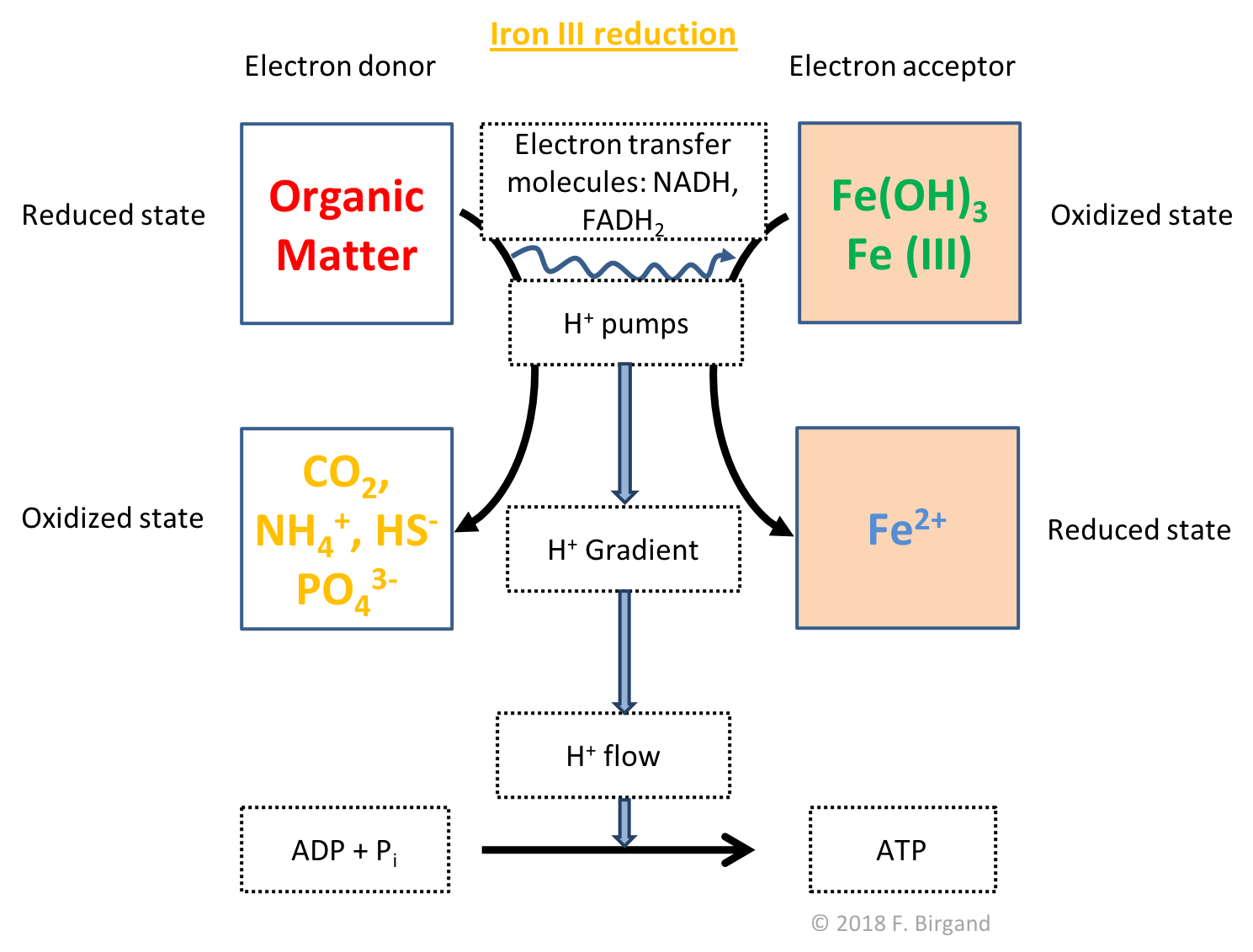

After the \(MnO_2\) oxides are reduced, the iron oxides and hydroxide minerals will similarly serve as electron acceptors following the general equation (??), and respiration scheme illustrated in Figure 8.7. The reduction of an iron hydroxide Fe(OH)3 has been added to show that in reality, \(Fe^{3+}\) never exists as such, but almost always as iron oxides or hydroxides. Many forms of iron oxides exist in soils, hence the choice of choosing iron hydroxide Fe(OH)3 in equation (??). \(Fe^{3+}\), Fe(OH)3, and other iron oxides are referred to as ferric iron or Fe(III), because their oxidation state is 3. Ferric iron generally has an orange rusty color. As \(Fe^{3+}\) is oxidized into \(Fe^{2+}\), it gains one electron.

Figure 8.7: Respiration scheme for heterotrophic Iron oxide reduction

The electron transfer chain for manganese has not been researched as much as that of Fe, although the latter still holds many unknowns. Many different proteins are involved, and may vary depending on the organisms. In a recent review, Bird et al. (2011) illustrate two identified pathways. The first one for Geobacter sulfurreducens (Figure 8.8) involves a suite of proteins referred to as Omp or Omc. The energy yield of the electron transfer seems rather low however. The extracellular location of the electron acceptor (Fe III) is energetically costly, particularly because the proton gradient between the periplasm and the cytoplasm is limited by the absence of proton consumption in the cytoplasm (as is the case for aerobic respiration when the electrons are accepted in the cytoplasm with the consumption of a proton along with it).

Using any external electron acceptor thus costs the cell one proton per electron transferred. The second reason for low efficiency is that the electron transport chain is short. In the current model of electron transfer to Fe(III), no energy is harvested after the electrons reach the periplasm. The amount of energy extracted from the electron transport chain therefore depends not on the potential difference (DE) between NADH and the final acceptor, but on the DE between NADH and the periplasmic acceptor. […] s. It therefore seems that Geobacter has adapted to use low-potential substrates [e.g. Fe(III) minerals] rather than maintaining an electron transport chain that would allow it to extract greater energy from higher potential acceptors(Figure 8.8; Bird, Bonnefoy, and Newman (2011)).

![(a) Electron tranfer chain for the organotrophic reduction of ferric iron (Fe III). NADH1, NADH dehydrogenase; MQ, menaquinone; PpcAD and OmcBES, cytochrome c-type proteins; OmpB, multicopper protein. (b) Schematic of reduction potentials of the Geobacter electron transfer pathway. Abbreviations: NTA, nitrilotriacetic acid; cit, citrate.scheme for heterotrophic Iron oxide reduction. from [@Bird2011-fs]](pictures/ETC-FeIII-reduction-geobacter.jpg)

Figure 8.8: (a) Electron tranfer chain for the organotrophic reduction of ferric iron (Fe III). NADH1, NADH dehydrogenase; MQ, menaquinone; PpcAD and OmcBES, cytochrome c-type proteins; OmpB, multicopper protein. (b) Schematic of reduction potentials of the Geobacter electron transfer pathway. Abbreviations: NTA, nitrilotriacetic acid; cit, citrate.scheme for heterotrophic Iron oxide reduction. from (Bird, Bonnefoy, and Newman 2011)

In their second illustration, Bird et al. (2011) show that Shewanella oneidensis does not use proton gradients and the ATPase to produce ATP, but rather uses substrate level phosphorylation to gain energy when reducing Fe(III). The hypothesis is that the oxidation of lactate to acetate is sufficient to produce ATP, and this substrate level phosphorylation can go on at the electron donated to NADH end up on \(Fe\) (III) (Figure 8.9).

![(a) Electron tranfer chain for the organotrophic reduction of ferric iron (Fe III) in *Shewanella*. MtrC and OmcA are thought to be donors to Fe(III). Whether they interact directly with solid Fe(III), chelated Fe(III), electron shuttles such as flavins, or all three is unclear. ATP generation takes place via substrate level phosphorylation. (b) Schematic of reduction potentials of the Shewanella electron transfer pathway. Arrow on scale bar denotes the energetically favorable direction. Blue arrows denote the aerobic path electrons take to O2, red arrows denote the path to Fe(III), and yellow bars denote potential ranges. The potentials of NADH1, bc1, and aa1 are simplified for clarity; in reality, each of these protein complexes has multiple redox centers and a range of potentials. Abbreviations: CymA, MtrA, STC, MtrC, and OmcA, c-type cytochromes; MtrB, outer membrane protein; UQ, ubiquinone; MQ, menaquinone; bc1, bc1 cytochrome complex; Cyt c, cytochrome c; aa1, cytochrome c oxidase; NTA, nitrilotriacetic acid; cit, citrate. from [@Bird2011-fs]](pictures/ETC-FeIII-reduction-Shewanella.jpg)

Figure 8.9: (a) Electron tranfer chain for the organotrophic reduction of ferric iron (Fe III) in Shewanella. MtrC and OmcA are thought to be donors to Fe(III). Whether they interact directly with solid Fe(III), chelated Fe(III), electron shuttles such as flavins, or all three is unclear. ATP generation takes place via substrate level phosphorylation. (b) Schematic of reduction potentials of the Shewanella electron transfer pathway. Arrow on scale bar denotes the energetically favorable direction. Blue arrows denote the aerobic path electrons take to O2, red arrows denote the path to Fe(III), and yellow bars denote potential ranges. The potentials of NADH1, bc1, and aa1 are simplified for clarity; in reality, each of these protein complexes has multiple redox centers and a range of potentials. Abbreviations: CymA, MtrA, STC, MtrC, and OmcA, c-type cytochromes; MtrB, outer membrane protein; UQ, ubiquinone; MQ, menaquinone; bc1, bc1 cytochrome complex; Cyt c, cytochrome c; aa1, cytochrome c oxidase; NTA, nitrilotriacetic acid; cit, citrate. from (Bird, Bonnefoy, and Newman 2011)

Although Shewanella does exist, the general scheme of the transfer of electrons from organic matter to \(Fe^{3+}\), and the proton motive force as the the main ATP synthesizing mechanism, as illustrated in Figure 8.7 holds in most cases and is sufficient for the big picture of respiration schemes.

Similarly to \(Mn^{2+}\) ions, \(Fe^{2+}\) ions, or ferrous iron, or Fe(II) is a dissolved iron which is mobile in water, and can diffuse following concentration gradients. For the same reasons explained above for \(Mn^{2+}\), an upward concentration gradient between zones 4 to 6 and layers 3 to 1 is going to appear and the \(Fe^{2+}\) ions will tend to diffuse upward through layers 3 and 2. The fate of \(Fe^{2+}\) ions as they reach the aerobic layer is discussed below.

This vertical spatial sequence of layers 3 and 4 presented here probably only applies not too long after the theoretical wetland soil has been flooded. Indeed, over the long periods, the supply of ferric iron and manganese oxides will run out, as the only supply is in immobile mineral forms. So over long periods, layers 3 and 4 do not exist. Is the case of a net downward water infiltration, the \(Fe^{2+}\) and \(Mn^{2+}\) ions diffuse upward all the way into the aerobic layer, and accumulate there for reasons illustrated below. In the more likely case of small but real net downward flux of water, the dissolved ions will leach out of the soil profile. The consequences are that poorly drained soils then to leach out their iron and manganese, which is referred to as iron and manganese depletion. This is the reason for the grey color of hydric soils (Figure 8.10).

Figure 8.10: Example of pale bluish gray redox depletions. Note the faint rusty orange concentration distributed throughout the soil matrix. Reproduced with permission © 2012 Nature Education All rights reserved.

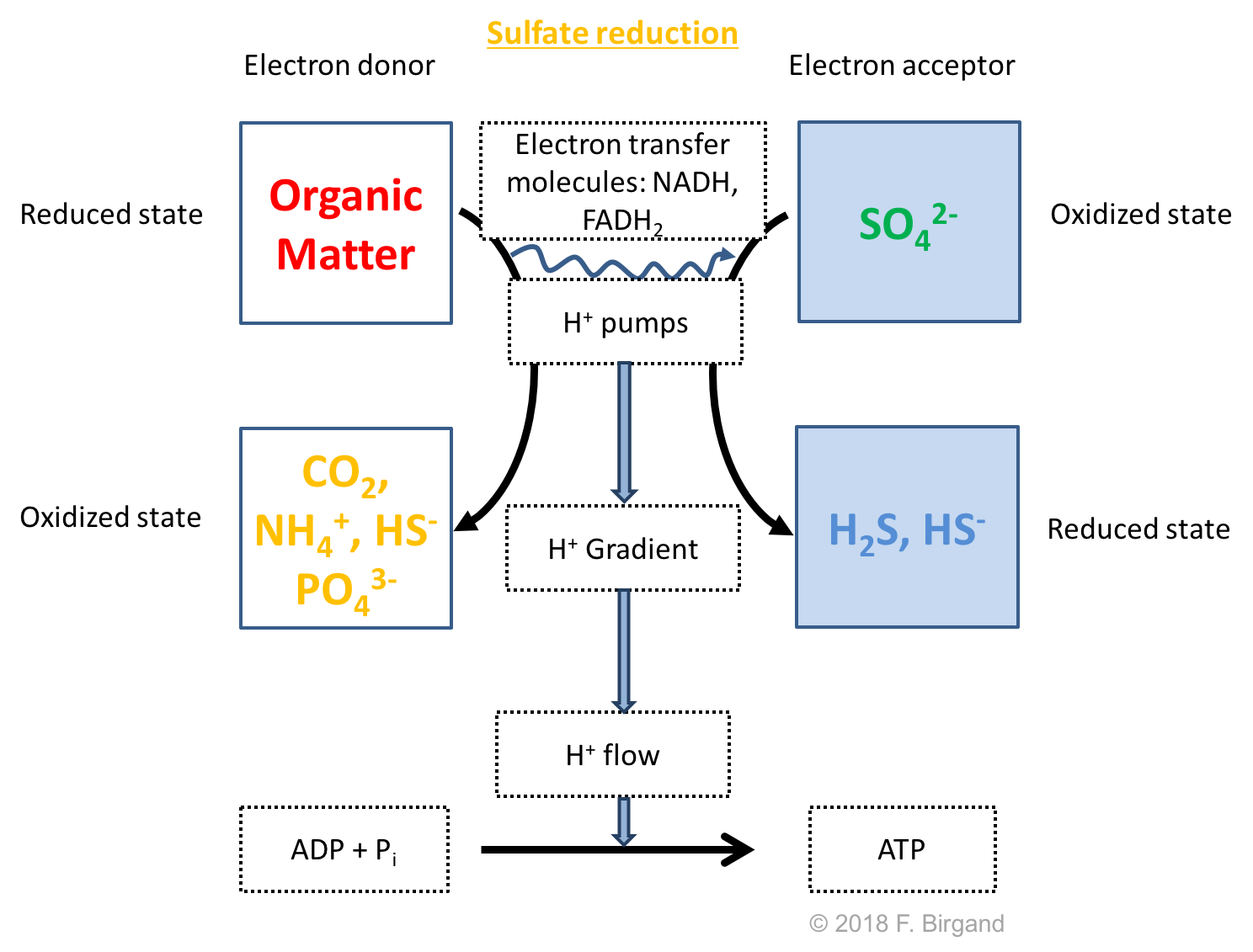

8.6 Sulfate reduction

After all previous electron acceptors have been used, sulfate becomes the next electron acceptor. As we have seen before, the sulfur atom on \(SO_4^{2-}\) has zero electrons for itself and it therefore can accept electrons following redox half-reaction equation (??). Sulfate reducing bacteria reduce sulfate into sulfide (S2-) and hydrogen sulfide (H2S), i.e., that the sulfur atom has gained 8 electrons. The respiration scheme below (Figure 8.11) suggests that Organic matter is generally the electron donor.

Figure 8.11: Respiration scheme for heterotrophic sulfate reduction

Recent reviews (Pereira et al. 2011; Barton, Fardeau, and Fauque 2014), suggest that more than one hundred compounds including H2, sugars, pyruvate, amino acids, mono- (lactate) and dicarboxylic acids (acetate), alcohols, NAD(P)H, and aromatic compounds are potential electron donors for Sulfate Reducing Bacteria (SRB). The presence of H2, formate, and acetate in the list of potential donors is symptomatic of the low level of redox potential, as these are often associated with fermentation processes. There seems to be a large variety of electron transfer chains depending on the exact SRB, involving many additional enzymes and proteins in the cytoplasmic membrane (Figure 8.12). In the end, however, ATP is still largely produced following the proton motive force at the ATPase thanks to proton gradients maintained by proton pumps.

![Summary of all identifed electron transfers in Sulfate Reducing Bacteria, as reviewed in [@Pereira2011-dt]. Observe the reduction of $SO_4^{2-}$ to S^2-^ in the left corner. Observe the ATP synthase to the right, and many sorts of proton pumps. Also observe several of the electron donors listed in the previous paragraphs. The exhaustive list of the abbreviations and correspondance can be found in [@Pereira2011-dt].](pictures/ETC-SO4-reducing-frontiers.jpg)

Figure 8.12: Summary of all identifed electron transfers in Sulfate Reducing Bacteria, as reviewed in (Pereira et al. 2011). Observe the reduction of \(SO_4^{2-}\) to S2- in the left corner. Observe the ATP synthase to the right, and many sorts of proton pumps. Also observe several of the electron donors listed in the previous paragraphs. The exhaustive list of the abbreviations and correspondance can be found in (Pereira et al. 2011).

Typical concentrations of sulfate in ground- and stream waters are between 1 and 10 mg \(SO_4^{2-}\)/L. In our theoretical wetland soil profile, sulfate that might be originally present in the porewater will be reduced in layers 5 and 6 of Figure 8.3. For the same reasons invoked for oxygen and nitrate, the potential source of supply for sulfate for the sulfate reducing layer is all the sulfate that might be present in the layers above and the water column. The demand for sulfate in layer 5 will create a downward concentration gradient which will generate a downward diffusive movement of sulfate down to layer 5. And again, because of all the diffusion distance, the supply of \(SO_4^{2-}\) is limited and does not match the demand. The imbalance between the sulfate supply and demand will limit the diffusion of sulfate to the bottom of layer 5, below which there will be no more sulfate.

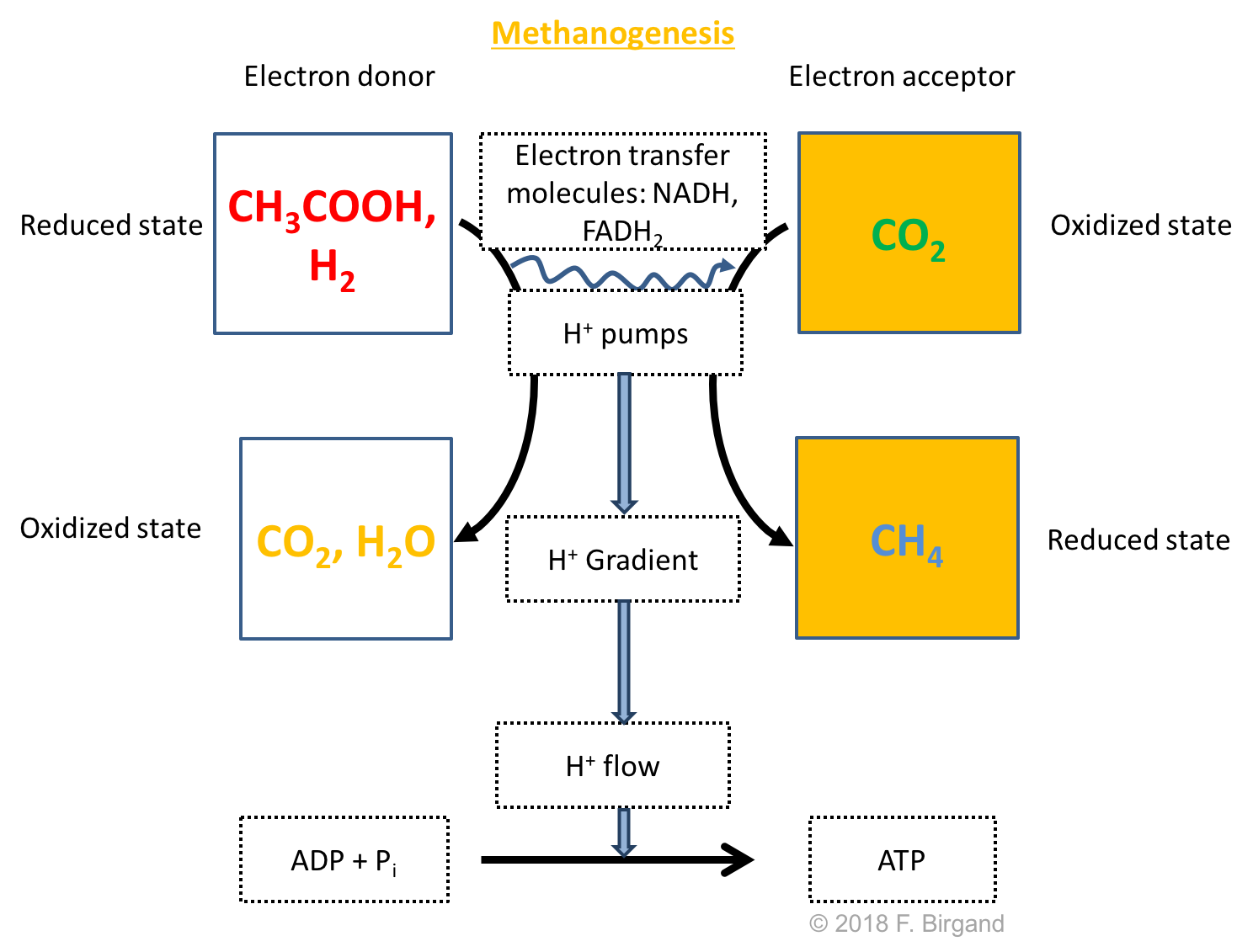

8.7 The methanogenesis oddity

The last redox reactions to take place at the bottom of our theoretical wetland soil uses \(CO_2\) as the electron acceptor. Interestingly, the generic organic matter is no longer the electron donor, but is replaced by two byproducts of fermentation processes: H2 and acetic acid CH3COOH as illustrated in Figure 8.13.

Figure 8.13: Respiration scheme for the heterotrophic Carbon dioxide reduction or methanogenesis

Because of the source of the electron donors, methanogens have to be physically located close to bacteria which metabolism is based on fermentation. In reality, in many cases “microbes interact via syntrophic associations, in which the metabolic by-products of one species serve as nutrients for another” (Hamilton, Calixto Contreras, and Reed 2015). And this is not only a property of methanogens (see below). The electron transfer chain of the methanogen bacterium Methanospirillum hungatei has been nicely illustrated by (Hamilton, Calixto Contreras, and Reed 2015) and is represented in Figure 8.14. Notice that ATP is, here again, synthesized by the proton motive force thanks to the proton gradient created by inverse flow of Na+. The latter is created thanks to sodium pumps powered by the oxidation of H2 (bottom right). The electrons lost from H2 are accepted onto \(CO_2\), which acts as the substrate, and the reduced carbon then becomes CH4, which is excreted out of the cell.

Figure 8.14: Summary of the Electron Transfer Chain for the methanogen bacterium Methanospirillum hungatei, which uses H2 as its electron donor. The exhaustive list of the abbreviations and correspondance can be found in supplementary information of (Hamilton, Calixto Contreras, and Reed 2015)

8.8 Fermentation in wetland and stream sediment

In reality, the redox chain presented above and in most textbooks avoids several important additional electron transfer mechanisms, because the latter tend to ‘muddy the water’ a bit on the otherwise clear theoretical description. The first of these is fermentation. In the previous chapter, we saw that the whole respiration process starts with glycolysis, which produces pyruvate

The fermentation products are beyond the scope of this class so, we will not come back to that, but it is important to recognize that H2 and CH3COOH can donate electrons as shown in these half-reactions:

8.9 First summary on the electron acceptor chain in wetland soils

- except for methanogenesis, organic matter always serves, for organotrophs, as the electron donor. Moreover, it is exclusively the Carbon of the OM which provides the electrons.

- as a result, the byproducts of the oxidation of the OM when the organic carbons lose their electrons are always the same: \(CO_2\), NH4+, H2S/HS-, and PO43- (but for methanogenesis). This means that at one point, all of these four (five if one counts both H2S and HS-, their exact proportion depends on pH, see details in the glossary) molecules will accumulate where they are produced unless they are used by another process

- To the contrary, the byproducts of the reduction of the electron acceptors are variable and depend on the electron acceptor. In the case of incomplete denitrification, and in the case of methanogenesis, N2O and CH4 are significant greenhouse gases.

8.10 Supply and demand of electron acceptors and of the byproducts of Organic Matter oxidation

Now that we have established the reduction processes of the different electron acceptors at play, let us look at the consequences of the demands and the supplies associated with the respiratory processes.

8.10.1 Demands drive downward fluxes of dioxygen, nitrate and sulfate

In the Figure 8.15 below, the general directions of the fluxes of electrons acceptors and byproducts of respiration are illustrated for our theoretical wetland soil. The processes taken together is sometimes referred to as soil or sediment diagenesis and all the processes in there are then collectively referred to as diagenetic processes.

Figure 8.15: Diffusion fluxes of electron acceptors and all other soil diagenesis processes of a theoretical layered wetland soil

The demands for dioxygen, nitrate, and sulfate in their respective layers, lower their concentrations compared to the overlying water and layers, hence the formation of concentration gradients, which then drive downward diffusive fluxes of these electron acceptors to their respective layers. These fluxes are represented as downward arrows in Figure 8.15.

Now, it is the imbalance between the supply from above and the demand from below, that explain why the downward diffusion does not go beyond the bottom of the respective layers 1, 2, and 5 in Figure 8.15. The limitation of supply has been described for dioxygen in section ??. The diffusivity, distance, and tortuosity of the soil pores also apply for nitrate and sulfate, and explain why the demand is generally not met by the supply.

8.10.2 Supply of byproducts of organic matter oxidation

For every respiration process described above (except for methanogenesis), the byproducts are: \(CO_2\), NH4+, H2S/HS-, and PO43-. This suggests that in every single layer, there is a supply of all for of these byproducts. Inevitably, this will create an upward concentration gradient, which will then be followed by an upward flux of these four molecules in the sediment.

Phosphate will thus dissolve upward, at least until it reaches the aerobic layer. There it might encounter soil mineral oxides where it might bind, as we shall see in future chapters, hence the tips of the arrows not reaching the soil-water interface. However, it is possible that, if the aerobic layer is very thin and the mineral oxides are scarce in this thin layer, phosphates may diffuse all the way into the water column, hence the dotted arrow.

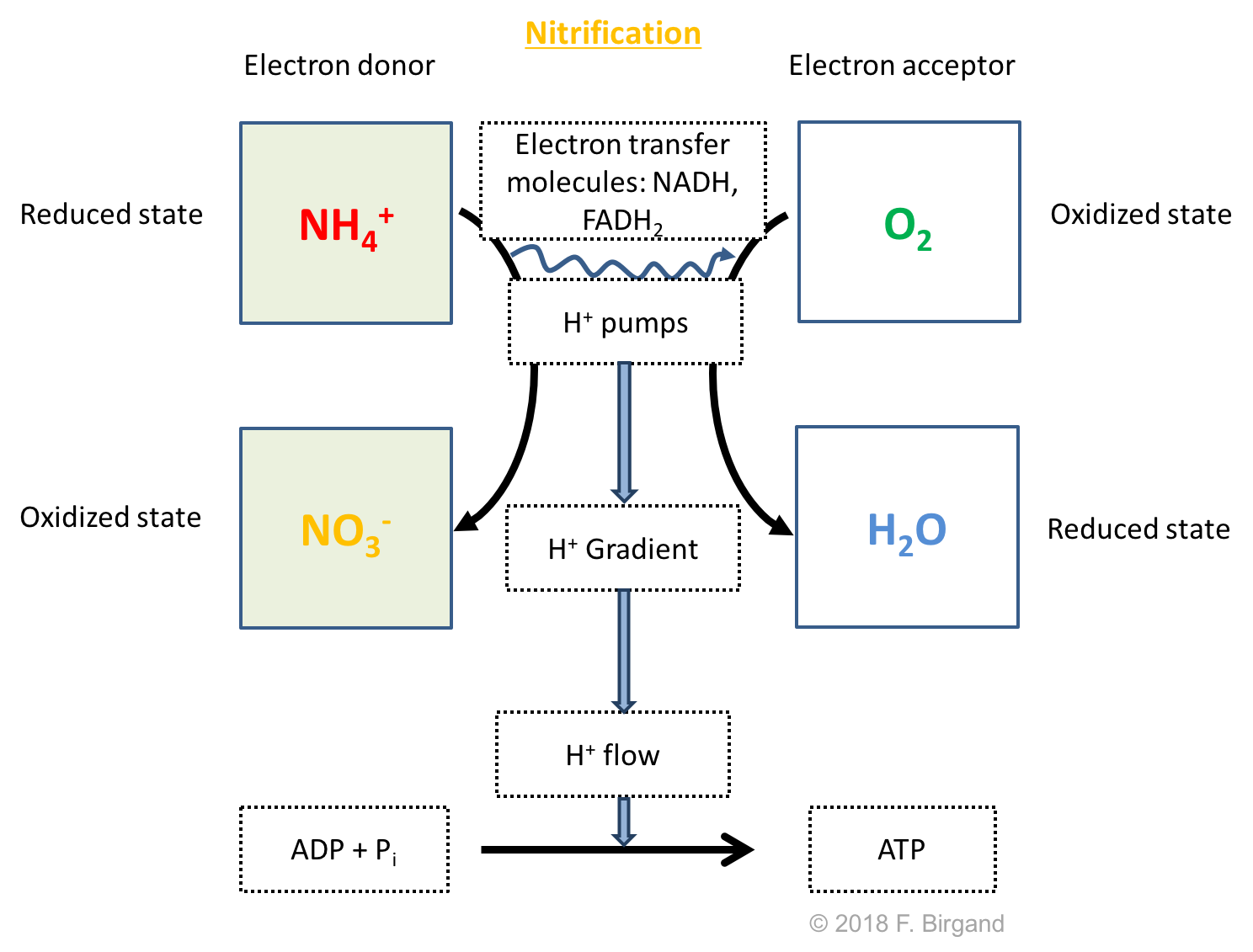

8.10.3 Nitrification

Similarly, because of ammonium production in all the layers, but that of methanogenesis, ammonium will diffuse upward, until it reaches the aerobic layer. Remember that the nitrogen atom on the ammonium carries 8 electrons for itself, so it potentially carries a lot of energy. And yes, you guessed right, microbes called nitrifiers take advantage of these electrons and use ammonium as their electron donors, and use \(O_2\) as their electron acceptor. Because the electron donor this time is not an organic molecule, nitrifiers are called lithotrophs. Nitrification is represented in Figure 8.15 as the horizontal white arrow to the left. The nitrification respiration schemes is summarized in Figure 8.16.

Figure 8.16: Respiration scheme for nitrification

Depending on the thickness of the aerobic layer and the availability of dioxygen, all or only a portion of the ammonium may get nitrified as ammonium moves upward, hence the dotted arrow going all the way to the water column. As nitrate is now produced in the aerobic layer of the soil, then the concentration gradient may sway upward or remain downward, depending on the nitrate concentration in the water column, hence the upward nitrate dotted arrow in Figure 8.15. You may also notice that a dotted white arrow pointing the left has been added to illustrate nitrification which tends to readily occur in the water column, often thanks to nitrifiers attached at the soil-water interface.

In reality nitrification involves two stages: the oxidation of ammonium into nitrite, performed by ammonium oxidizing bacteria, of which two important genera are Nitrosomonas and Nitrosococcus, and then the oxidation of nitrite into nitrate, performed by Nitrobacter and Nitrospira bacteria (Equation (8.2)). But as far as we are concerned, both steps tend to occur almost simultaneously, and nitrite is thermodynamically unstable, and as a result very little tends to accumulate, either in soil or sediment.

\[\begin{equation} NH_4^+ \rightarrow NO_2^- \rightarrow NO_3^- \tag{8.2} \end{equation}\]

Work in progress Denitrification chain image here. By Uswbios - https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=24910639

8.10.4 Gas bubble formation

Among the last two OM oxidation byproducts, \(CO_2\) and H2S are gases. We saw earlier, that in reality the balance between H2S and HS- depends on the pH. In rather organic soils, which most treatment wetland soils are, the pH tends to be rather acidic, often below 6.5. So it is fair to represent the H2S/HS- couple as H2S rather than HS- (see H2S/HS- Figure), hence the choice of H2S in Figure 8.15 and the use of H2S below.

So in the end, if the summation of partial pressure of these and all other dissolved gases exceeds 1 atm + the hydraulic head, gas bubble will form and migrate upward. But because of surface tension forces, gas bubbles tend to get rather easily trapped in wetland soils and sediment. Hence the release of wetland gases when somebody or something disturbs the sediment, as we have seen in lab. To these two gases, one should add the production of CH4 in the methanogenesis layer, which will readily ‘join’ the gas bubbles and the ride with them. The dissolved fraction will also tend to move upward because of the concentration gradient. Interestingly, methane does not oxidized very well in normal aerobic conditions of wetland soils, and will therefore tend to diffuse all the way up to the water column as illustrated in Figure 8.15.

Because of the demand for \(CO_2\) in the methanogenesis layer, downward arrows have been added for layers 4 and 5 in Figure 8.15. The downward diffusion would only apply for the dissolved \(CO_2\) as the gaseous form would obviously tend to move upward.

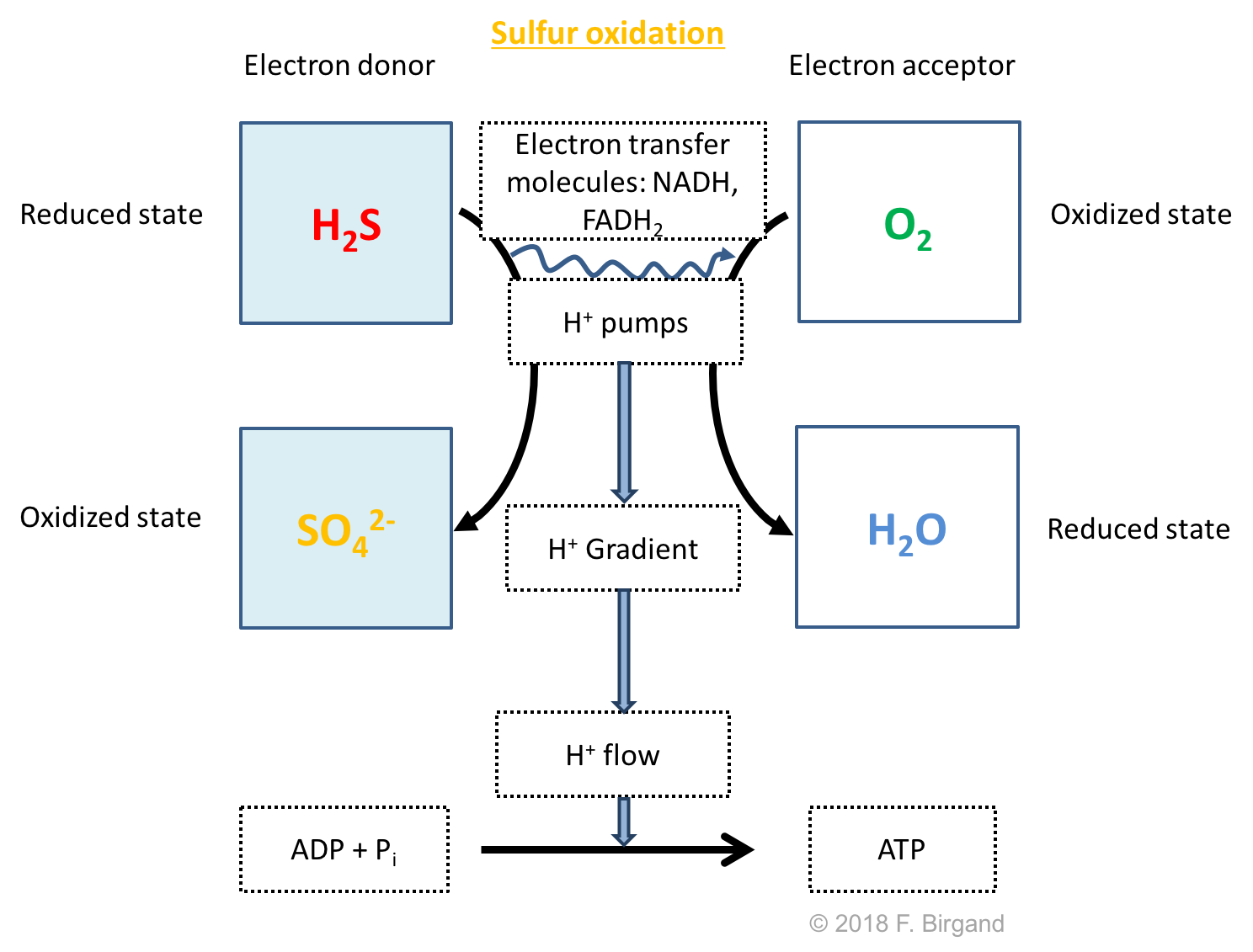

8.10.5 Oxidation of upward moving reduced sulfur

Similarly to ammonium, and although a good proportion of H2S will end up in the gas phase, a still significant amount will stay in solution and will diffuse upward until it reaches the aerobic layer. Very similarly to ammonium, H2S still carries 8 electrons, which can be used for respiration provided that a strong enough oxidizer be present. In the aerobic layer of the sediment, H2S will be oxidized back into sulfate following the respiration scheme in Figure 8.17

Figure 8.17: Respiration scheme for hydrogen sulfide oxidation

The bacteria taking advantage of the electrons on sulfur of H2S are called sulfur oxidizing bacteria. There are different from the sulfur reducing bacteria which use OM as their electron donors, and sulfate as their electron acceptors. The oxidation of H2S has been summarized by the white horizontal arrow in both the aerobic layer of the soil and the water column. Sulfate produced can then diffuse back downward to layer 5 in Figure 8.15.

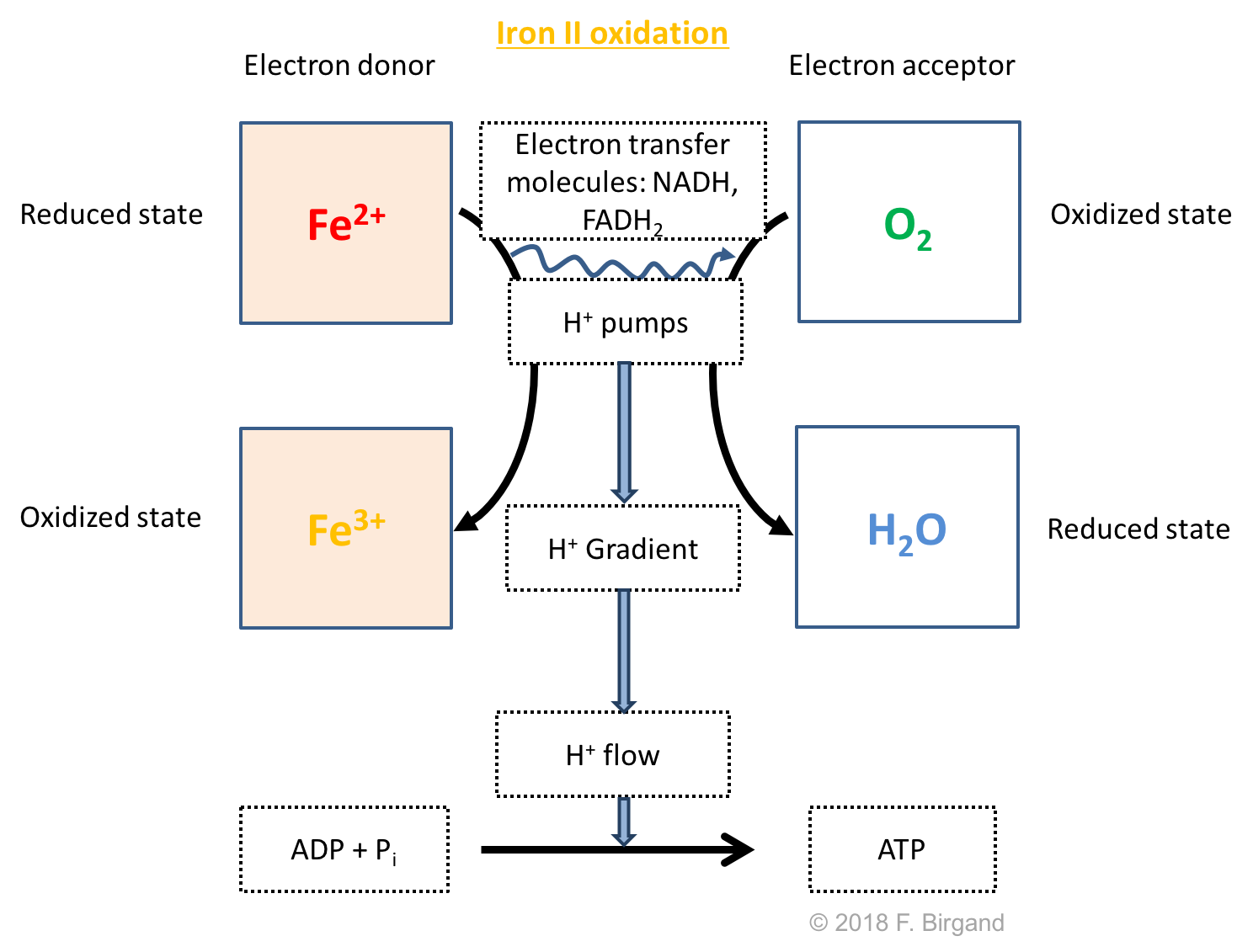

8.10.6 Oxidation of upward moving \(Mn^{2+}\) and \(Fe^{2+}\)

The last direct reduction byproducts of respiration processes include \(Mn^{2+}\) and \(Fe^{2+}\). Because they are being produced in layers 3 and below, an upward concentration gradient will be created, followed by an upward movement of \(Mn^{2+}\) and \(Fe^{2+}\). In Figure 8.15, both of them have been represented as starting to move up from layers 4. In all logic, \(Mn^{2+}\) and Fe2 should start moving upward as low as layer 6 because our original hypothesis was that soil was suddenly flooded, so in the temporal sequence of electron acceptors, before sulfate carbon dioxide reduction conditions would prevail in Layers 5 and 6, respectively, the \(Mn\) and \(Fe\) oxides will serve as electron acceptors, and \(Mn^{2+}\) and \(Fe^{2+}\) will then be produced.

The more important fact is the fate of both \(Mn^{2+}\) and \(Fe^{2+}\) as they reach the aerobic layer. Because they are both reduced, they potentially have one electron to give, and yes, some bacteria have specialized in the ability to oxidize these ions. These bacteria are referred to as manganese and iron oxidizing bacteria. The respiration scheme corresponding to iron oxidation is illustrated in Figure 8.18 below.

Figure 8.18: Respiration scheme for iron oxidation

As both \(Mn^{2+}\) and \(Fe^{2+}\) get oxidized in the aerobic layer of the sediment, they form \(Mn\) and \(Fe\) oxides, which are solids and precipitates with the other soil minerals, hence the underlying and downward pointing arrows under the \(MnO_2\) and \(Fe^{3+}\) in Figure 8.15. The precipitation of iron oxides or hydroxides can be quite visually spectacular sometimes as reduced groundwater seeps out into the open. Iron can get very quickly oxidized and form rusty biofilms.

Figure 8.19: Picture of an ‘iron seep’ in Goldsboro, NC, as reduced groundwater gets oxidized in contact with air

8.10.7 Moving of Dissolved Organic Carbon

The last but not least of the processes at play in diagenesis is the formation and diffusion of Dissolved Organic Carbon in poorly or anoxic soils. This is the subject of a future chapter.

This concludes this long chapter on the importance respiration processes occurring in wetland soils.